The Man Who Swam to Hong Kong

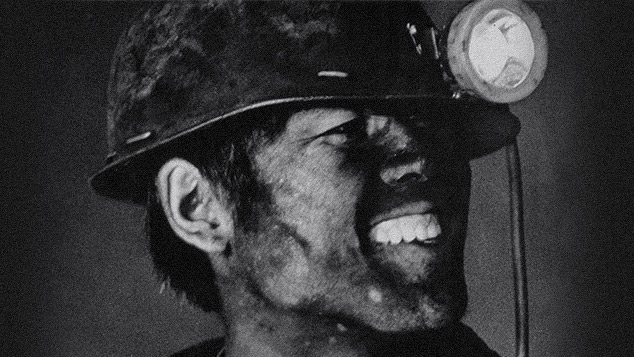

HONG KONG — Under dark clouds forming above Kowloon Bay, silver-haired Chan Hak-chi readies himself for a swim, as those around him begin packing up their gear to leave. “I’ve swum every day for the past 40 years, regardless of the weather,” the 70-year-old says, before turning away from the water and executing a perfect back dive into its dark depths.

It’s perhaps unsurprising that Chan isn’t bothered by the storm. Almost 44 years ago to the day, he braved much worse when he and his wife swam from the southern coast of the mainland through shark-infested waters to reach Hong Kong without any documentation.

Born in 1947, just two years before the founding of the People’s Republic of China (P.R.C.), Chan was raised in Guangzhou, the capital of southern China’s Guangdong province. The youngest of five children, he was a studious young man who had his sights set on going to college. But things changed in 1966 with the onset of the Cultural Revolution, a period of violent upheaval that targeted society’s perceived reactionary elements.

Like millions of other young people, Chan was promptly sent to the countryside — to a small county around 100 kilometers from Guangzhou — to toil among and learn from the rural working class, considered the foundation of the country’s socialist revolution. His dream of a college education lay in ruins, and he struggled to hold on to his hopes for a brighter future. His mother shared his despair; to Chan’s surprise, she implored him — albeit reluctantly — to take his then-girlfriend Li Kit-hing and leave the chaos of the Cultural Revolution behind by relocating to Hong Kong.

His mother’s wish followed several other booms in illegal migration to Hong Kong after the founding of the P.R.C., including one in 1962 following the Great Famine of 1959-1961. Another exodus was to follow in 1979 ahead of changes to Hong Kong’s settlement policy in 1980 stipulating that illegal immigrants from the mainland would be repatriated immediately.

In the ’70s, migrants like Chan had three options: slipping past border guards and their dogs to cross the land that connects Hong Kong’s Kowloon Peninsula to the city of Shenzhen in Guangdong province; navigating rocky sheer drops to the west and swimming across Shenzhen Bay; or braving the longer swimming route to the east through Mirs Bay, where people were known to have been killed by sharks in the choppy waters.

Chan and Li chose the eastern route — a hazardous and arduous swim, but one that was free of patrolling guards. “If there was a god who could have told us that the Cultural Revolution would end in a few years and that we’d get back to the city again, I wouldn’t have chosen to escape,” says Chan. “I really had no other choice.”

After months of swimming 10 kilometers every day in Guangdong’s Pearl River, Chan and Li felt as prepared as possible. On the night of July 16, 1973, the young couple traveled to the northern edge of Mirs Bay, connected themselves with a stretch of rope, and slipped into the sea.

After more than six hours of cutting through the waves, battered by the winds of Typhoon Dot, Chan and Li reached land. English writing on the trash that littered the shore told them they had arrived at their new home.

For the couple, who had never had an official wedding ceremony, the ordeal drew them closer together — so much so that they celebrate July 16 as their wedding date.

“Typhoon Dot was our witness,” Chan says. “The waves were our guests.”

What awaited them was nothing like a honeymoon. Chan and Li were able to register for Hong Kong identity cards under the “Touch Base Policy,” which granted residency to new arrivals from the mainland provided they made it to Hong Kong’s urban areas and were met by a relative; luckily, Chan had an aunt in Hong Kong who had migrated years before. But the couple’s relief at having settled safely was tempered by the harshness of the new life they had walked into.

With the help of Chan’s aunt, the couple found work in a factory making watch straps. They worked day shifts and night shifts, and would cover for fellow employees who went on leave whenever possible, each bringing home just 5 Hong Kong dollars (then around $1) a day. The financial pressure was compounded when, two years after they arrived, Li gave birth to a daughter, the first of three children for the couple. Chan tried his hand at all manner of trades — from watch factory worker to cotton mill laborer — taking on any work that would support the young family.

But by 1984, after a stint at an elevator installation company, Chan had saved enough money and gained enough experience to start his own elevator installation business. In 1995, all five family members moved into an apartment of their own in Hung Hom, where the elderly couple still lives with their two younger children; their eldest daughter is married and has three children of her own.

Now, when he isn’t busy diving in Kowloon Bay, Chan is savoring time spent with his children and grandchildren. That could soon change: His eldest daughter is considering moving abroad with her young family, a prospect that pains Chan, who says he is lucky to have come to Hong Kong and wears his profound attachment to his new home on his sleeve. “After I first arrived in Hong Kong, when people would ask me where I come from, I would say I’m from Guangdong province,” he says. “Now, at my age, I say I’m a Hong Konger.”

But Chan is also aware of the intense pressures facing Hong Kong’s younger generation — illustrated by the fact that his second daughter and son continue to live with their parents. His eldest daughter had no problem finding a well-paying job after graduating in 1997 with a degree in accounting, but his son, who graduated 12 years later, has struggled to find work. Without a stable, reasonably paying job, it's nearly impossible to afford real estate in Hong Kong, with figures from May showing that prices in the world's most expensive property market had risen for the 13th consecutive month.

“Many young people today have the desire to migrate,” says Chan, who now finds himself in a situation similar to his mother’s over 40 years ago, albeit under vastly different circumstances. “My mother couldn’t bear to see me go. And that’s how I would feel about my children and grandchildren if they left me.”

“My heart would be torn by their departure, but I would not stop them,” Chan says. “I would respect their decision.”

Editor: Owen Churchill.

(Header image: Chan Hak-chi goes swimming in Hong Kong, May 25, 2017. Wu Yue/Sixth Tone)