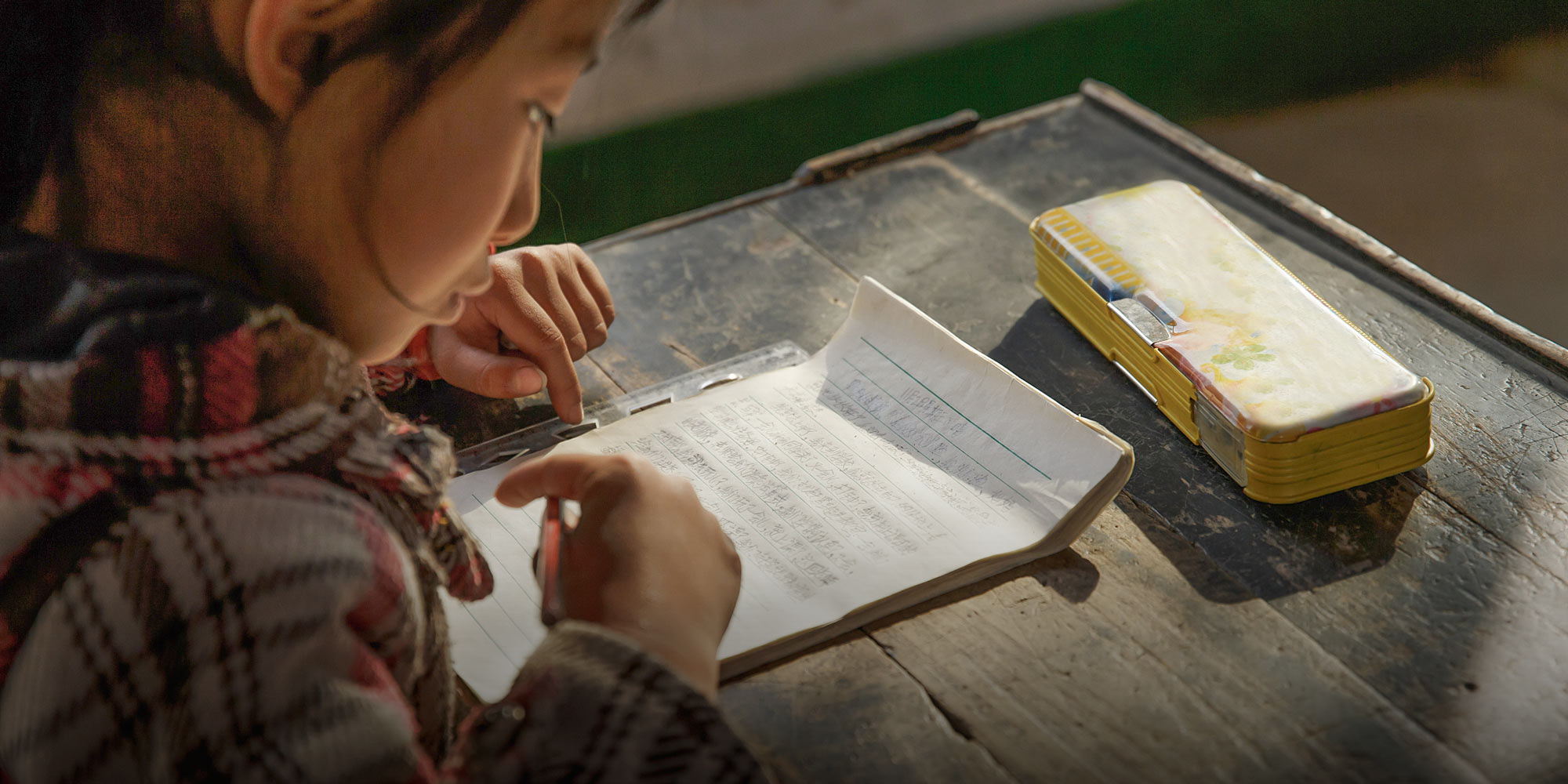

China’s Rural Children Are Cognitively Delayed, Survey Shows

Rural Chinese children have a significant delay in their cognitive development compared with their urban counterparts, researchers have found, which could potentially hinder the country’s economic development.

Of the 1,808 children aged 12 to 30 months old who were surveyed in rural counties of Shaanxi province, northwestern China, 57 percent scored below a certain threshold on an international infant mental development scale. The Rural Education Action Program (REAP), founded by Stanford University in California, in partnership with several Chinese institutions, published their findings earlier this month in The China Journal, a scholarly periodical.

Scott Rozello, a professor at Stanford University and the co-director of REAP, told Sixth Tone that these cognitive delays could mean China’s future labor force won’t be able to do the jobs of tomorrow. “When China has more innovation jobs and requires high-skilled labor, hundreds of millions of labor workers will not be able to participate in the economy,” he said. “China is facing a completely invisible problem.”

Preliminary results of REAP’s ongoing research in other provinces show that 54 percent of rural toddlers in Hebei province, northern China, are cognitively delayed, and that the rate is 71 percent among ethnic Han children in rural parts of Yunnan province, southwestern China. Meanwhile, at around 15 percent, the percentage in China’s more affluent rural areas is consistent with international averages.

While agreeing that the first years are pivotal for brain development, Zhang Xingli, a researcher at the Institute of Psychology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, told Sixth Tone that holding rural children to urban standards might be unfair. “This can have a negative impact on their confidence,” she said.

According to neurological research, most brain development occurs before age 3, and this formative period has a huge impact on an individual’s health, motivation, self-confidence, and ability to learn later in life.

A 1999 analysis of American families by an Ohio State University economist found that a child’s development is influenced by family background and income. In Shaanxi, REAP found that almost 40 percent of surveyed children were “left-behind.” They were not cared for by their mothers, but by relatives — often grandparents — because of the tendency for rural parents to migrate to cities in search of better-paying jobs.

In their July article, the REAP researchers discuss the connection between the parenting practices of left-behind toddlers and cognitive delay. Interviewees quoted in the report face difficulties in raising their children. One father interviewed by REAP, for example, said he doesn’t tell his child stories because the boy “can’t even follow basic instructions like ‘Don’t go outside’ — so how could he follow a story?”

“I explain to her what cats and dogs are,” said one woman describing an interaction with her daughter. “However, I can’t explain the animals she sees on television if I don’t know what they are myself.”

Editor: Kevin Schoenmakers.

(Header image: Viewstock/VCG)