Mute Museums? Not If You’re Chinese

In Rebecca Catching’s recent article for Sixth Tone, she made the cogent argument that China’s cultural institutions lack the narrative charm and the interpretive information required for audiences to adequately engage with the treasures on display. She cited a recent visit to one such museum where she and a colleague were left yearning for not only more information, but also, importantly, more stories.

Catching’s article went on to describe several visits to international museums where she was moved — via interpretive text, music, and narrative — to fully imagine and therefore engage with the broader context of the objects and their stories.

However, her conclusion that Chinese museums employ a top-down, curator-driven organizational model, to the detriment of other departments and audience engagement, doesn’t tell the complete story. Nor does the conclusion that employing content interpreters, or looking to privately owned museums to lead the way, fully stack up.

I don’t disagree that China’s museums can improve. However, it is important to remember that there were approximately 25 museums in China in 1950, and it is estimated that there are around 4,500 today — compared to over 45,000 in the United States. It is very much an emerging industry, one in which the mix of public and private, and the associated differences in operation and legislation, do little to establish consistent professional conduct.

I would like to focus on the three points that Catching raises: availability of information, narrative, and public versus private institutions.

It is true that the level of information about individual objects is usually reduced to material, date, dynasty, and discovery site. Catching suggests that this information should go deeper, explaining, for example, each type of vase, the significance of different designs, and the story behind each object — was it war booty? Did it belong to a great emperor?

But I feel that this statement misses the point. Chinese public institutions, unsurprisingly, focus on a domestic audience rather than international tourists. Chinese museumgoers tend to be incredibly knowledgeable about their country’s collective material history. I have visited many museums where a local can tell me in great detail the significance of an artifact’s design, the importance of its shape, and the story of the dynasty it comes from. The fact that essential information is presented in both Chinese and English is actually remarkable for a society that remained closed off to the world until fairly recently. In addition, there is generally more information given in Chinese, as Chinese visitors constitute the bulk of admissions.

It is important, too, to remember that much of China’s history remains contestable. It is a country with competing narratives, where even drawing up a map from 1000 B.C. can be contentious. Against this background, committing facts to labels can be interpreted — particularly in a public institution — as a political act that is best avoided.

Having worked at Te Papa Tongarewa, the national museum of New Zealand, which pioneered the narrative approach to exhibitions and employed content interpreters, I would suggest that this model, while somewhat successful with locals, was principally employed to reflect a shift in the museum’s focus to international visitors. When an institution relies on international visitors who are often ignorant of local culture for its financial well-being and attendance figures, it must become information-rich and narrative-focused. In China, however, the emphasis for public institutions is still on dominant local visitation.

Furthermore, the shift in focus toward narrative over dry academic information is designed to focus more on sociological narratives. A continuing criticism of this method is the tendency to dumb down academic content in favor of pluralistic storytelling, and to create exhibition experiences which, while exciting, leave little lasting impression. This is the difference between learning facts and learning anecdotes. Anecdotes can be marvelous, but they often don’t impart immediate material knowledge. While it may be true that Chinese institutions rely heavily on academic interpretation, many museums in Western countries now rely far too much on effects — particularly new, exciting technologies such as immersive projection scenes and virtual or augmented reality — so that visitors remember much about the experience but little about the actual objects.

As a final point, while there are many private museums appearing all over China, few are better-funded than their public counterparts, reliant as they are on either wealthy benefactors or property development companies with secondary agendas. In terms of the number of visitors — and there are scant other ways to measure success among the world’s museums — the Shanghai Museum is still one of the most popular in China, with 1.9 million visitors per year, making it the 29th most popular globally. No private institution yet measures even close to that figure — although numbers from both types of institutions in China are difficult to verify.

In comparison to the Shanghai Museum, at least one private museum anecdotally described having several hundred visitors for an exhibition opening, and then dropping back to around four visitors per day. In addition to the poor visitation rates of many private institutions, there is the lack of professional support: The most significant private contemporary art institutions in Shanghai don’t even employ curators, let alone content interpreters, and their collections have been described by international experts as being kept in woefully inadequate conditions.

Catching sees hope in private museums, but I see more hope in private-public partnerships, where the shortfall in funds can be offset by private donors, allowing public scholarship to fully tell stories that increasingly diverse audiences want to hear. I hope, too, that increased partnerships will broaden debate, expand on China’s contestable histories, and allow both institutional narratives and personal stories to flourish in spaces that are accessible to national and international audiences alike.

Many institutions — both public and private — are now using QR codes to deliver additional levels of information, and more are experimenting with emergent technologies to create ever deeper layers of experience. With each new layer, however, there is a need for further technical, academic, interpretive, and budgetary support, which many renowned international institutions are struggling to maintain. Only 40 years old, Chinese museums are nonetheless making the sort of extraordinary progress that most international institutions can only dream of.

Editor: Matthew Walsh.

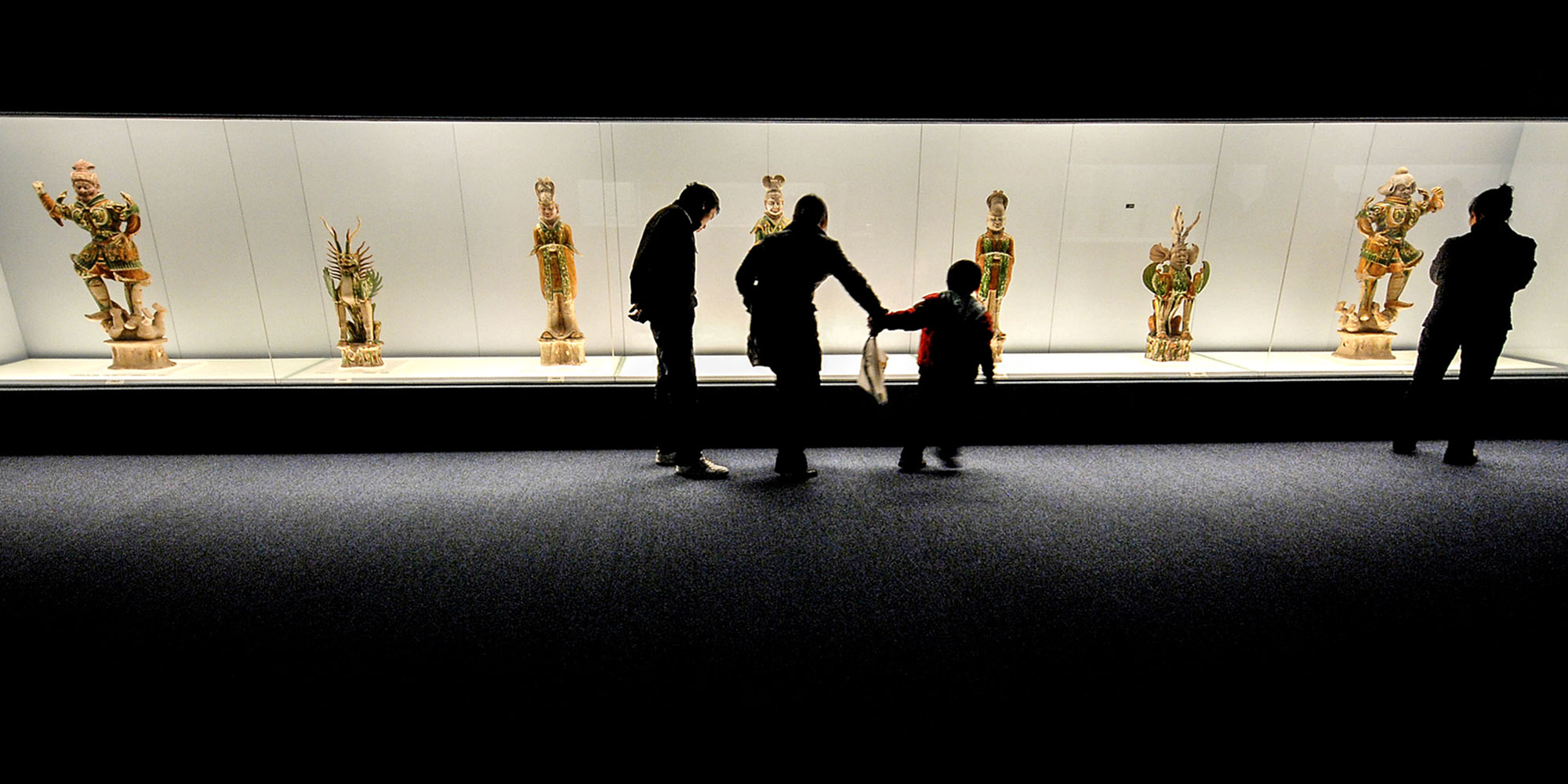

(Header image: Visitors look at ancient Chinese glazed pottery at the Shanghai Museum in Shanghai, March 4, 2008. VCG)