Family Trees Make a Comeback Among China’s Retirees

BEIJING — Guo Yiping grew up listening to legends of his family’s past: the conquests of Guo Ziyi, one of the most powerful generals of the Tang Dynasty; the arduous trek undertaken by 18 relatives, who traveled roughly 400 kilometers west from Shaanxi province to what is now Inner Mongolia in northern China to escape famine.

But written records, even of his forebears’ journey — one of the largest migrations in Chinese history — were scant. As Guo later discovered, all of his family’s genealogical documents had been burned during the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s.

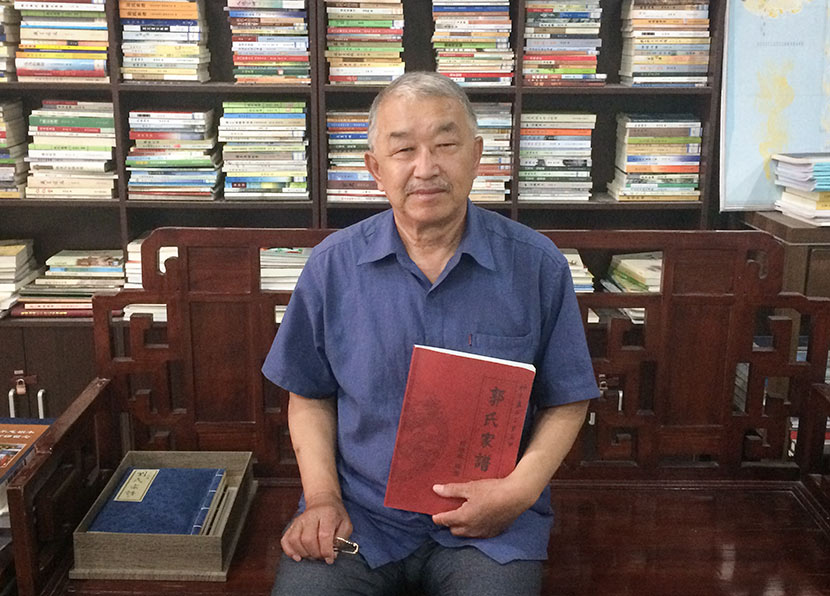

“Genealogy carries the essence of Chinese people; it’s what makes us different from people of other countries,” explained Guo, now a retired 62-year-old who works as a part-time Chinese tutor. “Our ancestors valued genealogy greatly and saw it as the history book of the family. Otherwise, how could our people have carried on for 5,000 years?”

Genealogy, or the study of family history, was ridiculed during the Cultural Revolution as being one of the “Four Olds” from feudal society: old customs, old culture, old habits, and old ideas. But after Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping kicked off a period of economic reform in 1978, the study of genealogy gained favor once again — starting in Taiwan before spreading to affluent areas on the Chinese mainland, especially coastal cities in Zhejiang, Jiangsu, and Guangdong provinces.

China’s rapidly aging population may be contributing to the renewed interest in documenting the past. According to the Ministry of Civil Affairs, the number of people above 60 years old exceeded 222 million by the end of 2015, accounting for 16 percent of the total population. By 2050, one out of three people in China will be over 60, estimates the China Association of Mayors.

Once retired, these elders often turn their attention to cultural pastimes, which can include rediscovering their ancestral heritage. “Compared to young people, elders have more time and savings in the bank,” said Tu Jincan, who runs a publishing business that helps customers compile their family histories. He believes that as Chinese society continues to age, the genealogy industry will grow along with it. It wasn’t until Guo retired in 2005, for instance, that he decided to take on the challenge of compiling his genealogy.

“Whenever I think about the hardships my ancestors experienced, it leaves me in tears. After retiring, I felt responsible for rebuilding our genealogy,” Guo said.

A sense of familial duty is also what drew Tu to genealogy: A well-known Chinese parable on filial piety from his hometown in Xiaogan, central China’s Hubei province, inspired him to quit his job teaching Chinese and start his publishing business. The local legend describes the life of Dong Yang, a poor but loyal son who sells himself into slavery to pay for his father’s funeral.

In 2008, Tu began his venture, mainly focusing on biographies and family histories. He started off in Hubei and the southern city of Shenzhen — known as a business hub — before eventually moving to Beijing, which has a larger elderly population.

Today, Tu’s business publishes more than 300 books for some 500 customers every year, with almost half the orders coming from Beijing. In the past decade, his company has witnessed steady growth, reaching about 300,000 yuan ($44,650) in monthly revenue. Meanwhile, the starting price for publishing 50 copies of a work has increased from 2,000 to 3,000 yuan.

In addition to editing genealogies, Tu’s team — which currently includes 22 full-time employees — conducts interviews, checks facts, and researches their clients’ family histories. Some genealogies take several years to compile, depending on the size of the family.

It’s no small feat, given the mass destruction of written records during the Cultural Revolution. Guo had to travel to almost 90 villages across Shaanxi and Inner Mongolia, as well as to Beijing, in order to collect information about his family lineage. He set off in 2006, using 30,000 yuan of his own money to cover his travel fees.

“Many of my family members turned me away, since most of them are villagers and aren’t aware of the importance of genealogy,” he recalled. Still, after working on the project for five years, he raised another 33,000 yuan from 18 relatives whose names were added to the new compilation of the family’s history.

Finding a publisher also proved difficult, as it isn’t profitable for large companies to publish just a few dozen copies of a text. After meeting Tu in Beijing, however, Guo was finally able to publish his 339-page tome, which includes narratives and photos of the remaining 10 Guo families. It also details family trees, historical migration routes, and Guo’s own experience compiling the genealogy.

Besides the aging population, another reason why Tu says he’s optimistic about the genealogy market — despite having had to lay off a third of his staff at one point — is because the central government is now encouraging the revival of cultural traditions.

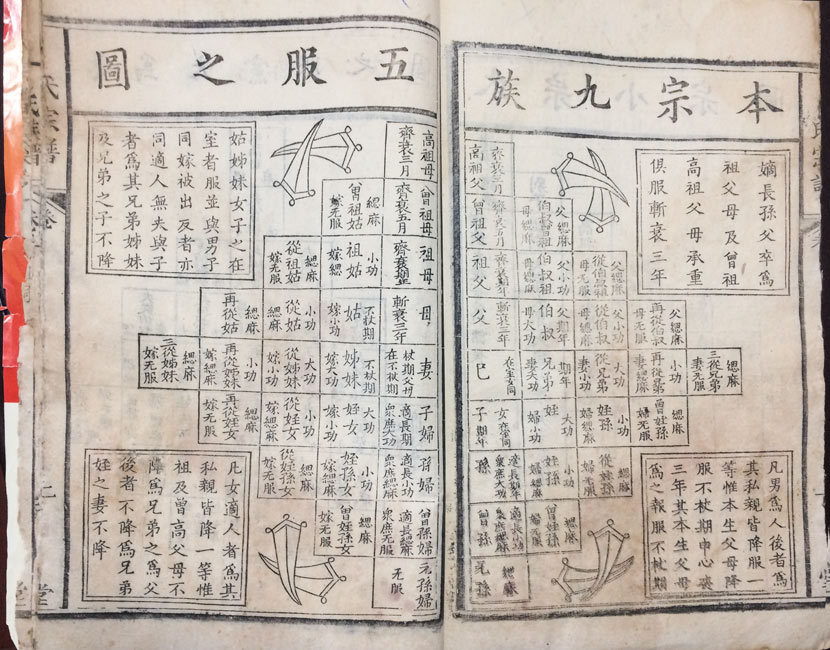

According to Wang Heming, a genealogy expert at Shanghai Library, China’s genealogy tradition can be traced back as far as the Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 B.C.), when oracle bones were used to record names and dates. For a long time, however, the practice of recording family histories was exclusive to the elites — such as during the Tang Dynasty (618-907), when royal families compiled genealogies as evidence of their political and social status as well as their claim to the throne.

It wasn’t until the Song Dynasty (960-1279), when the government began selecting imperial bureaucrats from among the general public, that genealogy became more widely practiced. In addition to tracing bloodlines, it was also a way for elders to lay down family rules and values — a kind of handbook for future generations. “Genealogy is like an encyclopedia of Chinese families,” said Wang.

Tu believes the family values mentioned in some Chinese genealogies are evidence of the changing times: Past genealogies often emphasized the father’s rule over his sons, Tu says, whereas today’s compilations focus more on respecting elders and cherishing the young. In addition, modern genealogies tend to be more inclusive of female family members, whose names and stories were typically absent from older records.

Increasing affluence among Chinese families may be another reason why genealogies are seeing a revival, according to Wang. “They’re starting to become more aware of the importance of respecting ancestors in this way and are more willing to spend money on it,” he said.

Li Rengui, another of Tu’s customers, spent more than 100,000 yuan compiling his own family history. Unlike Guo, Li’s family had kept an old genealogy dating back to the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), but it hadn’t been amended in 70 years. Creating an updated record of his family’s past was his biggest dream before retiring, he said.

The last few centuries have been tumultuous for the Li family. During the Ming Dynasty, they were considered nobility, but over the last 200 years, the family fell into abject poverty. At their most prosperous, however, several of Li’s ancestors were elected government officials.

It can be difficult to ensure the accuracy of ancient records, as authors sometimes exaggerate the importance of their relatives or include fake ties to royalty, said Wang. Members of Li’s family, for instance, claim they are related to Li Shizhen, a well-known Ming Dynasty doctor. Li, on the other hand, said he hasn’t found proof of the connection — only that his family and the famed physician came from the same village.

Between 2012 and 2016, Li updated information on 700 family members with the help of three relatives. Now, the 66-year-old is working on a new project to revise the past 100 years of his family’s history.

“The value of genealogy is to see the ups and downs of the family,” said Li. “I feel deeply touched when I read the biographies of my ancestors.”

(Header image: Guo Wenhai (center), Guo Yiping’s great-uncle, poses with relatives in a photo from 1964. Courtesy of Guo Yiping)