How a Remote Ethnic Group Is Torn Between Tradition and Modernity

During the summer vacation after the first year of my master’s course in anthropology, my advisor suggested that I go study the Mang people, a minority group living near the China-Vietnam border. Even today, very little is known about this group, whose small population calls the region’s mountain forests home.

There are only about 700 Mang people in China, most of whom live in Jinshuihe Township in the southwestern province of Yunnan. Traditionally, the Mang eked out an isolated existence as farmers, lacking access to electricity, clean water, and basic sanitation. But with the support of the government’s poverty alleviation efforts since 2008, this impoverished community has succeeded in adopting a more prosperous way of life.

The Mang people once depended on slash-and-burn methods for growing rice and corn, along with hunting, gathering, and fishing as supplementary food sources. This lifestyle led them to migrate periodically from the mountain forests, such as when the soil grew less fertile. To more sedentary ethnic minority groups living nearby — such as the Hani and Dai — they were like ghosts, wandering without a home.

After permanently migrating from the forest, the Mang community split into three village teams — the administrative units governing villages. In 2009, the Mang were classified as part of the Blang ethnic minority, becoming the last minority group within Chinese borders to gain official recognition.

At the time, I was curious about how the Mang had changed after experiencing rapid modernization. I set off from Kunming, the capital of Yunnan, and finally reached Jinshuihe Township’s Nanke Village — deep in the mountains — on my third day of traveling. Covering an area of 115 square kilometers, Nanke comprises 10 groups of villagers.

Under the poverty relief efforts in 2008, villagers reclaimed part of the Nanke River and leveled a small hill to make room for construction projects. Locals built a small three-story structure to house the village committee, as well as a new marketplace out of colored steel, complete with a tiled rooftop. They also added a new entrance to the village elementary school. When I reached Nanke, the first thing I saw were brick buildings — but I slowly realized as I walked through the village that nestled between those modern structures stood many crumbling shacks made of mud and held up by planks of wood.

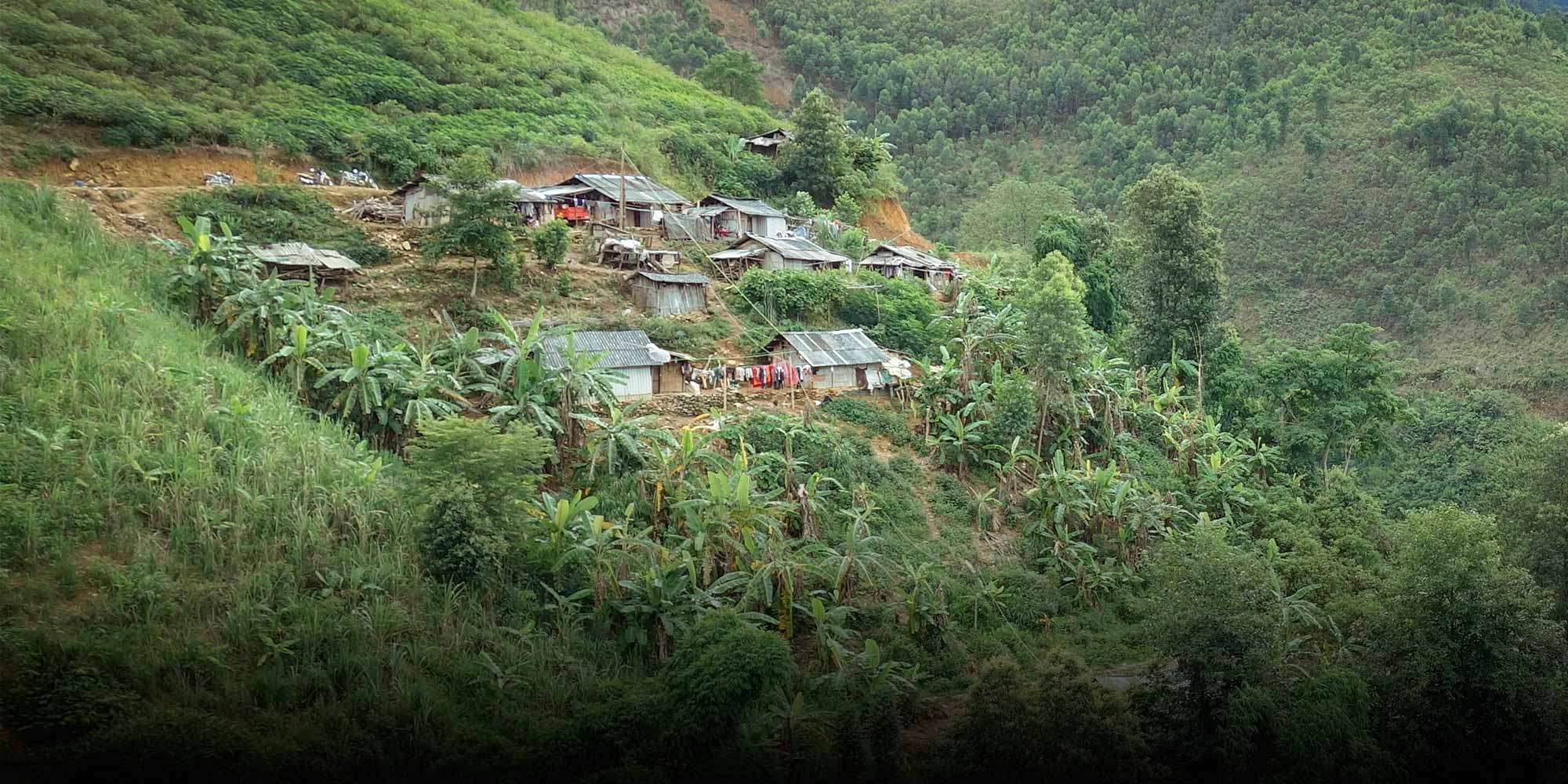

Nearby, on a slope overlooking the Nanke village committee building, lies Mang New Village, less than a 20-minute walk away. Compared to Nanke, the government aid-sponsored two-story buildings erected here looked neater, but behind this cluster of black-tiled, white-walled residences were shacks housing young people who had moved out of their parents’ homes. They were waiting for the next wave of poverty alleviation projects — with no idea when it would arrive.

In addition to helping build Mang New Village, the relief projects also encouraged the Mang community to plant cash crops, especially sugar cane. With these changes to their livelihood, they began interacting more with the outside world. In the past, their main contact with outsiders came from bartering in the markets, but the arrival of TV, modern health care, pension insurance, schools, and sugar cane crops has since deepened these interactions significantly.

For a large part of their history, the Mang people’s way of life revolved around subsistence farming. Beyond that, a small portion of their produce was traded at the market in exchange for necessities they couldn’t produce themselves, like salt and clothing. Although their quick transition into modern society has improved their living conditions, it has also destroyed their traditional way of life, leading to schisms within the Mang community.

When relief measures were first rolled out, many residents were willing to stay in the village and work in agricultural production. In my interviews with these people over several months, many said that they believed they could benefit from the policy, and that as long as they could find suitable cash crops, they would inevitably be lifted out of poverty into riches. However, their location deep within the mountains made it extremely hard to grow sugar cane, while the income gained from the project was only enough to cover basic provisions.

After experiencing the outside world, some young Mang people began to regard their hometowns as impoverished, stifling, and dirty, so they started migrating to Shanghai, Beijing, the southern city of Guangdong, and other places to find jobs. But their lack of skills forced them to rely on their fellow villagers to introduce them to assembly line jobs for meager remuneration. Unable to adjust to the outside world, some returned to the village, but new generations of young adults still often seek new lives elsewhere.

One villager whom I’ll call Luo San was born in 1993 and is the third brother of the head of Mang New Village. Luo left in September 2015 for Dongguan, a city in southern China’s Guangdong province, staying with a fellow villager who had found work there. When I visited Mang New Village in February last year, the village head and his mother said that nearby Jinping County had a vacancy at a public institution where the hiring policies favored the Mang people, and they hoped that Luo would test for the position. Despite the low pay, it was a stable job, but Luo turned it down because he didn’t want to return to the village. Since then, he has refused to answer his family’s phone calls.

The young adults I’ve met who leave their homes in search of jobs all return because of the same issue: identity cards. In China, citizens must be 16 years old before they can apply for their ID cards, the information on which is essential to sign a labor contract, buy a mobile phone, or purchase air and train tickets.

However, many Mang youngsters leave the village as minors. As it is difficult to obtain an ID card away from their hometown, they return to Yunnan and wait for the three-month process to end. These young people find it tedious to spend that much time at home: Life is dull, and there is no 4G mobile phone signal or internet cafés. They may complain about living elsewhere — saying that Guangdong is hot, that the pay is low, and that people there scam them — but they bolt out of town as soon as they get their ID cards, taking with them a handful of other villagers.

Most Mang people feel caught between staying in the village and moving to the city. Against this backdrop, it is as difficult for villagers to sustain their traditional way of life as it is to adjust to life outside. Their struggle is the same: a recurring conflict between tradition and modernity. A decade after the poverty relief projects started, modernization remains as alarming and bewildering as it has always been.

Translator: Katherine Tse; editors: Lu Hua and Matthew Walsh.

(Header image: Newly built shacks housing young people who have moved out of their parents’ homes in Mang New Village, Yunnan province, June 16, 2015. Courtesy of Tao Anli)