Invisible Millions: China’s Unnoticed Disabled People

Today, Dec. 3, is the International Day of Persons with Disabilities, an occasion that intends to put the spotlight on a group of over 1 billion individuals and accord them the same dignities, rights, and happiness that able-bodied people enjoy.

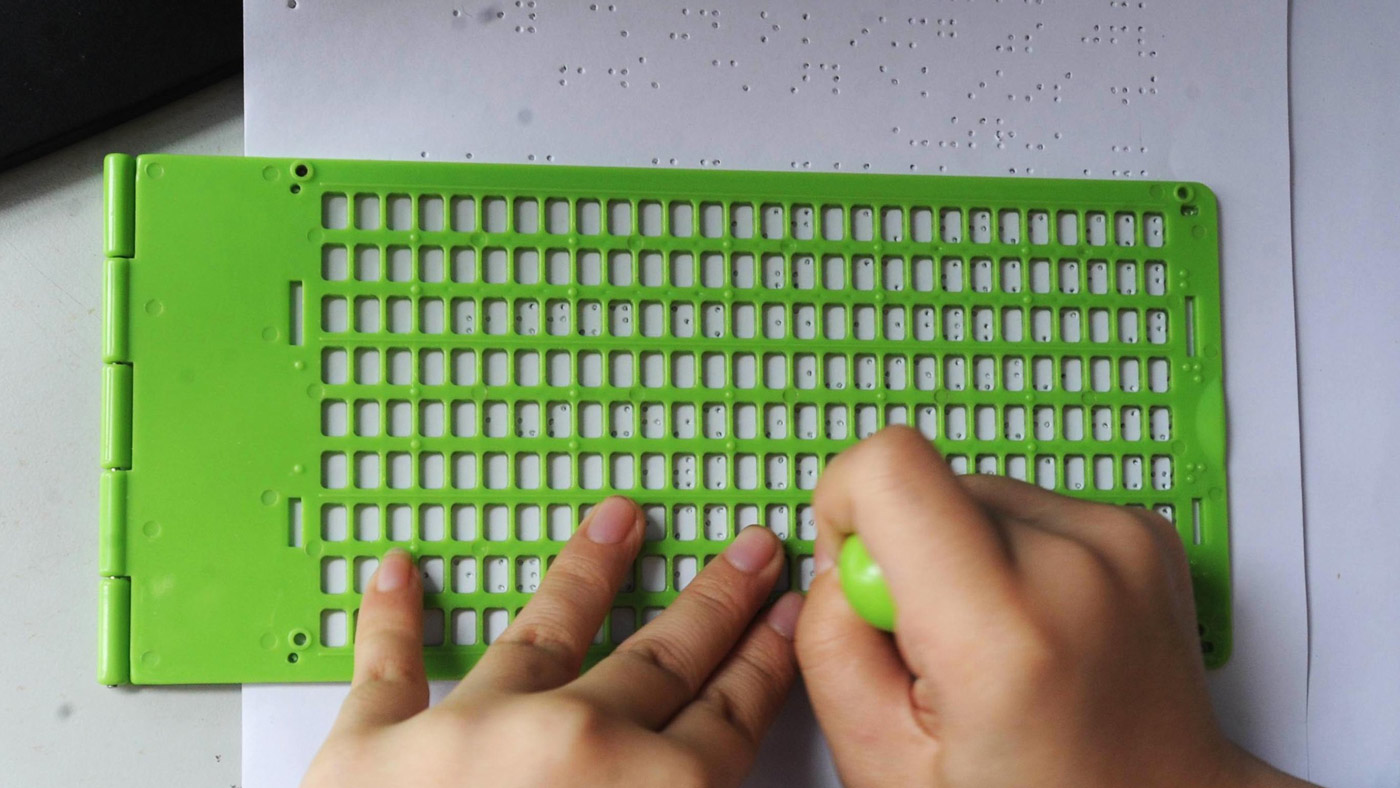

According to the China Disabled Persons’ Federation (CDPF), more than 85 million people identified themselves as living with disabilities on the 2010 national census. But in China’s public spaces, they are largely invisible. Few people actually use the braille buttons in the elevators, the wheelchair-friendly ramps at banks and post offices, the lanes with tactile paving for the visually impaired, or the accessible bathrooms in malls.

For some time, disabled people in China were referred to as canfei, a combination of two characters meaning “incomplete or deficient” and “useless.” From the 1990s onward, people started using the word canji, changing the latter character to one meaning “disease or sickness.” This term is still used today.

Canfei carries a strongly pejorative implication and is rightly no longer being used. However, the term canji is not perfect either, as it insinuates that disabled people have some kind of incurable ailment that renders them abnormal. Unfortunately, this is how many Chinese still view disability today.

As the disabled community has reframed the debate in human rights terms, though, alternative terminology has been proposed. More and more signs now describe disabled people as canzhang (replacing the second character with one meaning “obstacle or barrier”) or use a completely new phrase: shenxin zhang’ai, or “physically or mentally obstructed.”

The emergence of these new words is a positive development, as they emphasize that it is society that highlights our flaws much more clearly than our own bodies. Disabled people face obstacles precisely because social institutions are unable to effectively accommodate the physical and mental differences among people. It’s not that people with disabilities are inherently flawed; it’s that our environment is not accessible enough.

There is, of course, a tangible aspect to the idea of accessibility — that is, the facilities in public places that are baseline guarantees of mobility for disabled people. Even in China’s most developed cities, many streets pose challenging obstacles for people with disabilities: Sidewalks end abruptly, ramps are so steep that wheelchairs sometimes overturn, accessible elevators stay locked, and bathrooms are jammed full of cleaning supplies. One reason that disabled people are rarely visible in public is simply because it is too difficult to go out. Accessible facilities thus sit unused, fall into disrepair, and are often abandoned.

At the same time, technology has dramatically improved the lives of many disabled people: Screen-reader software and cochlear implants are two such examples. Yet if we refuse to deepen our understanding of accessibility, technology will also have its limitations and even create new hindrances. A wheelchair-using friend once described how she was trying to use an ostensibly disability-friendly video teller machine, similar to an ATM, that allowed bank customers to manage their accounts without waiting for counter service. The machine told her to face the built-in camera and take a picture to verify her identity, but she couldn’t sit high enough to frame her face. A friend and a bank clerk had to physically lift her up to take the picture, an experience she found very demeaning.

It is difficult for able-bodied people to empathize with their disabled counterparts, as the latter represent a minority. The less often disabled people show up in public, the less their needs are seen or heard. To adapt to a world in which most people carry an “able-ist” mindset, they force themselves to try to overcome their disability at the expense of their dignity. Another friend of mine told me that she avoids going to the bathroom whenever she leaves the house: “I want to go, but can’t find anywhere that I can use, which makes me feel a little less human.”

The accessibility that we see in public life is a manifestation of how our institutions frame the very notion of access. These institutional hindrances force many disabled people into another, more deeply structural, kind of invisibility.

When it comes to understanding people with disabilities, the Chinese media usually tout two diametrically opposite ideas. The first is the so-called encouragement model, represented by the current CDPF chairman, Zhang Haidi, as well as a number of Paralympic champions. This model stresses that disabled people might be “broken in body, but strong in spirit” and lauds exceptional individual efforts to achieve things despite their disabilities.

The second approach is the hardship model, which depicts disabled people as physically frail victims of misfortune who need society’s help. This view imbues the culture around disabled people with a feeling of pity and seeks to generate public empathy for their plight.

In both of these models, the vast majority of disabled people — commonplace individuals trying to live normal lives — are largely absent. These gaps in understanding lead to prejudices about people with disabilities. For instance, social media users commenting on stories related to disability regularly express sentiments such as, “If disabled people can do it, then I have no excuse to slack off,” or “With all your health problems, it’s better to stay home and rest than to go out.”

Such remarks have prompted Xie Renci — a Chinese disability advocate who made headlines earlier this year for publicly displaying her prosthetic leg while traveling to the country’s remote regions — to speak out against becoming “inspiration porn,” channeling the remarks made by Australian disability rights activist Stella Young during a 2014 TED talk.

Chinese people should be directing our efforts at shattering the notion that disability is abnormal. Disabled people should have the same expectations as able-bodied people. If we assume that disabled people somehow lack the ability to live and work normally, then they will face discrimination when it comes to everyday life and work. Similarly, if we assume that disabled people can excel through sheer willpower, then we risk eroding China’s systems for safeguarding disabled rights.

While 85 million Chinese identified as disabled in 2010, only 32 million people were certified as disabled as of last year. In China, legal recognition of disability comes in the form of a certificate issued by the CDPF. That certificate effectively functions as a kind of identification allowing disabled people to access a range of national and regional benefits.

These policies vary because disabilities are ranked according to severity, but they primarily include living allowances, access to medical services, social security initiatives, tax breaks, and scholarships for disabled students, and employment support.

There are a range of legal incentives for companies to hire people with disabilities, but significant numbers of uncertified disabled people are rejected from jobs because their disabilities don’t conform to the set standards. Without greater institutional protection and assistance, millions of disabled Chinese will continue to face significant barriers to access and remain invisible to the rest of society.

Correction: The encouragement model is most commonly associated with participants in the Paralympics, not the Special Olympics.

Translator: Katherine Tse; editors: Zhang Bo and Matthew Walsh.

(Header image: A volunteer pushes a wheelchair-using child in Chengdu, Sichuan province, Dec. 3, 2012. IC)