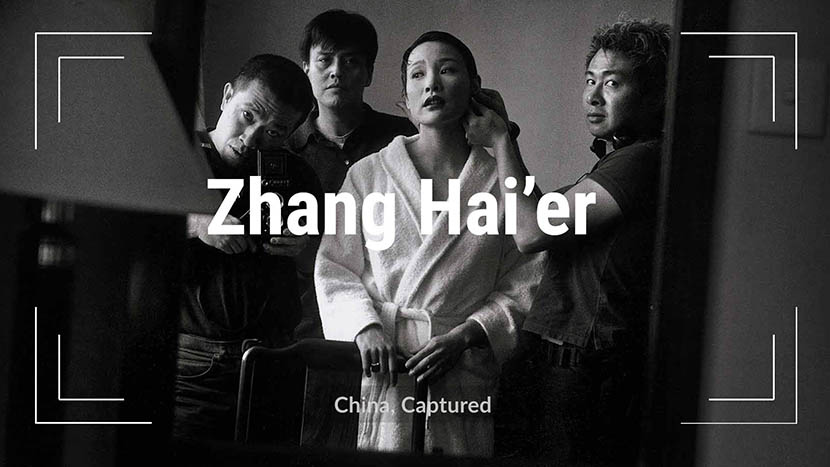

China, Captured: Zhang Hai’er Gazes at the Country’s ‘Bad Girls’

This is the second part in a series about some of China’s most renowned photographers.The first article can be found here.

Zhang Hai’er is a man of many talents. The magazine photographer, photojournalist, and artist has photographed everyone from migrant laborers to Chinese crossdressers, via projects focusing on the country’s women and LGBTQ communities.

For years, Zhang shot behind the scenes at high-end fashion shows in Paris as a contract photographer for several magazines. But in China, most people recognize him from “Bad Girls,” a series of portraits of women taken in the 1980s and 1990s. The female subjects of his photos are in various degrees of undress, revealing their legs or cleavage in playful, sometimes flirtatious ways.

In 1988, Zhang was one of the earliest Chinese photographers to be presented at Les Rencontres d’Arles, a prestigious annual photography and art festival held in France that gave the world a chance to see the abovementioned women. “The reason his ‘Bad Girls’ portrait series stood out at Arles with such distinction is because most people at the time didn’t think that such [women] existed in China,” says Christian Caujolle, founder of the photo agency Agence Vu, and Zhang’s collaborator.

One way to understand Caujolle’s assessment is to look back on Zhang’s childhood and creative history. Born in the southern Chinese city of Guangzhou in 1957, Zhang was sent to the countryside in 1974 for re-education during the Cultural Revolution. He took the college entrance exam when it was reinstated in 1977 and won a place at the Shanghai Theatre Academy to study stage design.

After graduating in 1982, he married his college classmate, Hu Yuanli; the couple is still together today. In 1985, he was admitted to the masters’ program in oil painting at the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts. Around that time, he began taking photographs of his wife and the women around him, slowly settling on photography as a mode of self-expression.

To understand Zhang’s work, we must consider the monumental changes he experienced during the 1970s and ’80s, as China transitioned from the hyper-Maoist fervor of the Cultural Revolution to an era of reform and opening-up that kickstarted its unprecedented economic growth.

Throughout Mao Zedong’s rule over China from 1949 to his death in 1976, women were portrayed as tough and warrior-like. The government claimed to have liberated women from the yoke of Confucian patriarchy and encouraged them to join the workforce and participate in social affairs. Though female emancipation in early Communist China was not the transcendental experience it is often portrayed, most women were still being valued for their work, not their bodies, for the first time in Chinese history.

The mobilization of the female labor force, however, did not seek to liberate female identity or sexual desire. Women were still expected to be chaste, and their de-sexualization stifled them — and their male counterparts — from expressing themselves romantically and sexually.

In the 1980s, as China’s economic reforms began in earnest, the art world tended to depict women either as virtuous and virginal, or as resilient and maternal. Men, too, remained sexually restrained, peering timidly at these images of women and avoiding open discussions of sexual attraction. Zhang broke this taboo: His realistic portrayals of women’s bodies captured their emotional and physical reactions at particular moments, bringing the often hormone-ridden male gaze into the open for all to see.

Zhang’s photos were utterly groundbreaking at the time and kickstarted a trend of using photography to explore repressed sexuality. His works untethered sexual desire from shame; in doing so, he granted desire a greater degree of legitimacy.

There is tension in the air in each of Zhang’s photographs, as his subjects acknowledge and react to his presence in such traditionally intimate settings. While we might expect the crushing pressure of tradition to render Chinese women shy, modest, and demure, in Zhang’s works they stare boldly, sometimes even mischievously, back at the male gaze. They look dangerous; they misbehave. They are not chaste — at least, not in the traditional sense.

Zhang believes that good art must subvert and topple long-held ideas and push back against social restraints. But as gender politics has come to focus on the representation of women in art, photographers have sought to combat the male gaze in their visual works, decrying it as a reductive perspective that sees women as sex objects for straight male viewers. Zhang’s early work, once lauded for its frank portrayal of female sexuality, has now come under renewed scrutiny for filtering images of women through a masculine prism.

“All I’ve done is praise the indisputable beauty of the flesh and the goodness of sexuality,” Zhang tells Sixth Tone, saying his work is not a projection of male desire onto the women he shoots, but are collaborations between him and his subjects that allow both parties to express themselves.

Zhang claims to be a feminist at heart, but more than that, he says he is a staunch defender of sexual freedom. His feminism aligns with the controversial open letter penned by 100 French women and published in Le Monde, saying the #MeToo movement — in which women are encouraged to call out male abusers — has gone too far, and that society should safeguard the “freedom to seduce.”

Zhang has always worked with sexuality. Since snapping the abovementioned women in his early years, he has documented the Pride parade in France and people who identify as non-gender binary. Over 30 years, this naturally introverted photographer has wielded the camera both subjectively and objectively, both to express himself and to capture the faces that define an era.

Translator: Katherine Tse; editors: Ming Ye and Matthew Walsh.

(Header image: Ma Tao, Shanghai, 1998. Courtesy of Zhang Hai’er)