Douyin Suspends Ads After Martyr Misstep

Short video app Douyin has suspended advertising operations following an online marketing gaffe last month.

The hugely popular app found itself in hot water when a web user discovered that it appeared in search engine results advertising jokes about Qiu Shaoyun, a revolutionary martyr who died in 1952. The incident came barely a month after China’s new law protecting the reputation of “heroes and martyrs” came into effect on May 1.

Qiu was a Chinese soldier who fought in the Korean War. In the face of a raging fire, he reportedly chose to stay still and burn to death rather than move and betray the location of his comrades. School textbooks have since heralded Qiu as a hero and martyr.

Last month, however, web users found that when typing “Qiu Shaoyun” into search engine Sogou, the top result was a paid listing for Douyin titled “Jokes about Qiu Shaoyun getting burned.” On Saturday, Douyin, Sogou, and three digital consultancies connected with the search result were “invited to talks” with Beijing regulators and told to rectify and reform.

The Beijing Internet Information Office announced that the companies had been asked to improve their approval processes for advertising and educate their staff on regulations, core socialist values, and revolutionary history. All five involved companies stated they would reform “according to demands and temporarily halt advertising operations,” said the notice.

Heroic tales of martyrdom and self-sacrifice aimed at inspiring patriotism in students have been taught in schools for decades. Primary school textbooks, for example, often include Qiu’s tale, as well as the story of Lei Feng, a young man hailed as a model worker in the 1960s who died after being hit by a telephone pole that fell as he was helping an army truck to back up.

But with such stories taking on near mythical status, they become natural fodder for irreverent jokes and memes. In September 2016, a Beijing court ordered an internet celebrity and an herbal tea manufacturer to apologize to Qiu’s family after making jokes about the revolutionary martyr on microblogging site Weibo.

Now the government has taken a firm stand with the law protecting “heroes and martyrs,” which bans any activities that defame them or distort and minimize their deeds.

Only days after the law came into effect in May, a man was sued for spreading misinformation online about a firefighter who had recently died. The same month, Baozou Manhua, a popular comedic content producer, was pulled from several platforms for a clip in which a masked man pokes fun at two war heroes.

On another front in China’s history wars, media watchdogs have also banned spoofs of “classic works” and revolutionary literature.

Yet while many Chinese netizens protested the shutdown of joke app Neihan Duanzi in April, Weibo users largely seemed to support the action against Douyin: A post from Party newspaper People’s Daily about last weekend’s meeting has garnered over 60,000 likes.

“[How about you] shut down Douyin?” reads one highly upvoted comment under the post. Another user wrote: “What on earth are those videos? Kids are being brainwashed!”

Editor: Qian Jinghua.

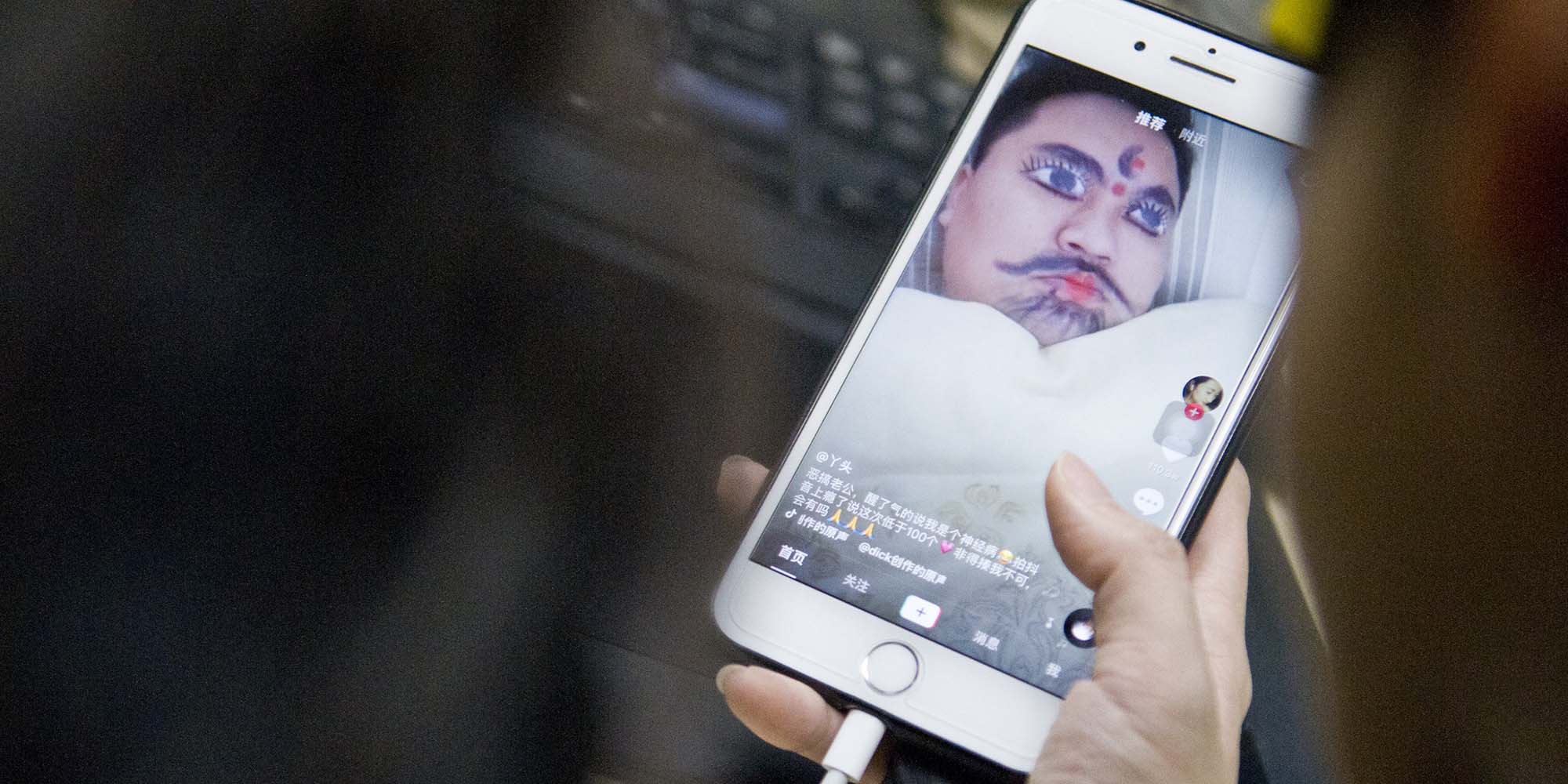

(Header image: A Douyin user watches a short video on the app in Guangzhou, Guangdong province, March 22, 2018. IC)