Shelf Life: China’s Independent Bookstores Plot a Revival

Tucked away behind a patch of bamboo, the Luming Bookstore has been a sanctuary for intellectuals since it was founded over two decades ago. When Gu Zhentao and his business partner opened the store back in 1997, both were graduate students in Chinese literature at Shanghai’s prestigious Fudan University. They chose to name their establishment after a poem from the ancient literary classic “The Book of Songs,” in the hopes that it would attract a literary-minded clientele.

Not much about how the store is run has changed since, and its shelves remain as scrupulously curated as ever. Yet while Luming still stands, many of its peers are disappearing, casualties of the struggles physical bookstores everywhere have faced over the past few years.

As a manager, Gu is well aware of the challenges online retailers present for independent bookstores, but he remains reluctant to make concessions to the market. “You could say that we are among the very few shops still trying to preserve traditional [bookstore] values … but maybe we’re just too stubborn to change,” he jokes.

China’s physical bookstores are trying to recover from a difficult decade — in part caused by the emergence of price-slashing online rivals — during which their book sales decreased rapidly. According to a report presented at a publishers’ forum held in Beijing in January, brick-and-mortar book retailers finally reversed this long-lasting downward trend in 2017, increasing their sales by 2.33 percent.

Luming has not been immune to the industry’s difficulties. In late 2013, with the store’s lease running out and the landlord unwilling to renew, Gu spent months looking for a new site. “It was hard to find a place that was both suitable and affordable,” he says. Word soon spread that Luming would close, and netizens began mourning the loss of what many saw as the last independent bookstore in Shanghai’s university area.

It was this last part that proved key to Luming’s rescue. Soon after hearing about the store’s predicament, the operations arm of Fudan University — Gu’s alma mater — reached out and offered him 200 square meters of space for a new store. Luming is now located in the heart of Fudan’s main campus in northeastern Shanghai, where it neighbors the undergraduate student dormitories and several teaching buildings.

Instead of charging regular rent, the school established a partnership with Luming whereby Gu pays Fudan a percentage of the shop’s revenues each month. The university controls the store’s marketing and takes care of cleaning and maintenance, but Gu says Luming retains full control over what appears on the shelves. Fudan’s motives may not have been entirely altruistic though. As Gu notes, having an independent academic bookstore like Luming matters to the school. “It would be a great pity for a university to not even have a bookstore,” he says.

The partnership between Fudan and Luming is by no means unique, and it seems the authorities are starting to recognize the importance of bookstores. In June 2016, 11 Chinese government departments jointly announced a plan to subsidize and develop brick-and-mortar bookstores around the country. This July, Beijing launched a 50 million-yuan ($7.3 million) project to provide relief to 150 bookstores in the capital, with an emphasis on “distinguished, unique, and neighborhood” establishments.

While government aid may seem to offer an out to bookstores in dire financial straits, in the long run it will eventually be up to the shops themselves to find viable business models.

Gu thinks the answer for independent bookstores is to do more than just curate a selection of books for curious readers. He believes they should act as “thought leaders,” teaching Chinese readers about their country’s rich cultural heritage. “Parents today want to immerse their children in traditional culture, but the available material varies widely in quality,” he says. “I believe this is where we can be of service.” At its new location, Luming hosts conferences and gatherings related to literature and history, run by scholars from universities all over China. Gu hopes such activities will inspire public interest in classic works.

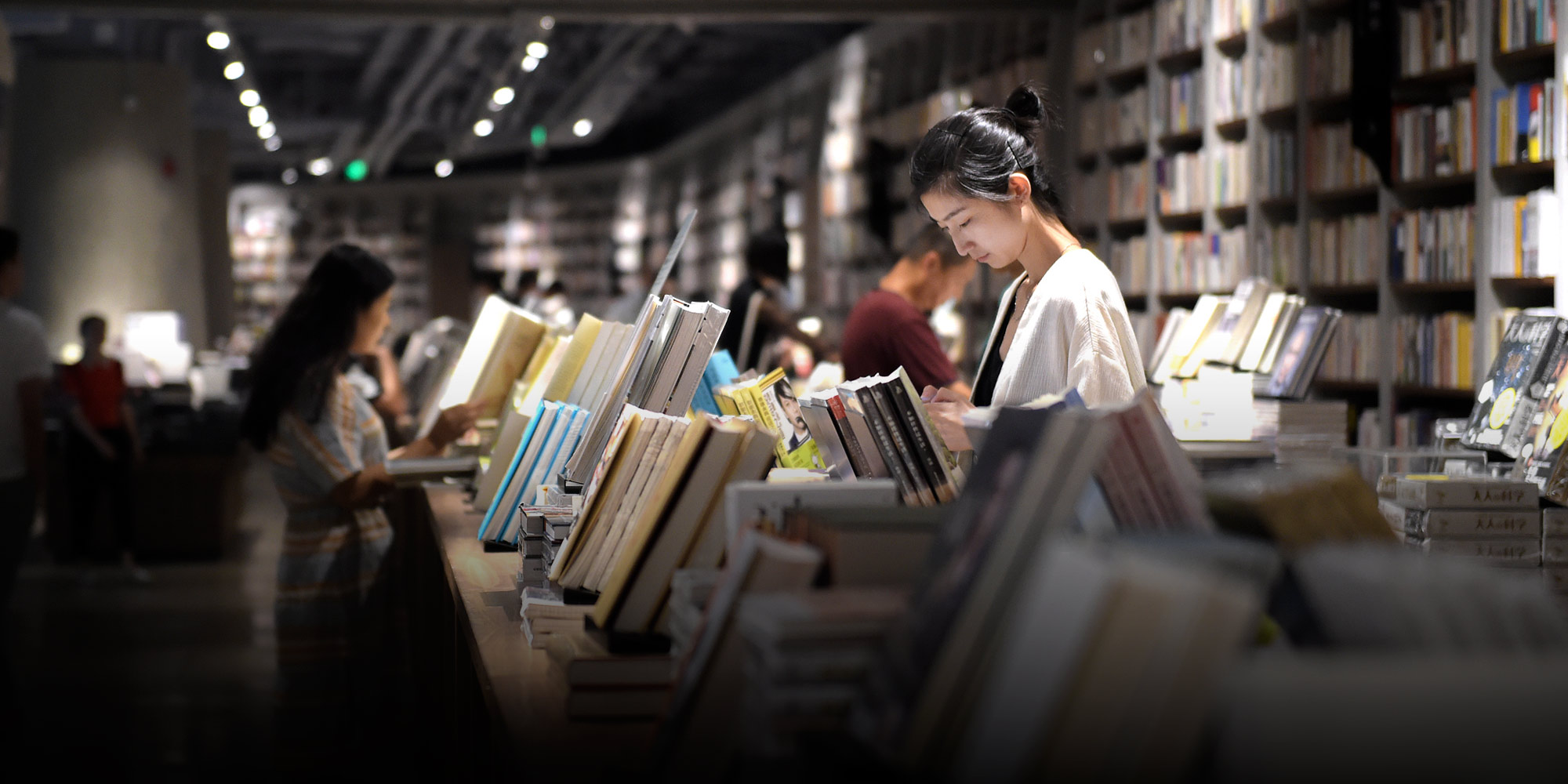

But Gu’s isn’t the only potential path forward. Other bookstores have sought to diversify their business to better compete with online retailers. Such reinvented stores see themselves as not only a bookstore, but also a coffee shop, an art gallery, and more. Chains like Sisyphe, Yanjiyou, and Fangsuo draw in customers with stylish cafés, cozy chairs, and vintage incandescent lighting.

But Gu is unimpressed by this business model. “Their customers are looking for an experience: ‘Oh, I’m in Fangsuo reading a masterpiece by a prestigious historian while drinking a cup of coffee — that’ll make a perfect WeChat Moments post,’” he says, explaining what he sees as the prevailing mentality among patrons at these stores.

Yu Tingting, a researcher at the Fangtang Think Tank in Beijing, agrees. She has written several articles calling modern chain bookstores representative of the “triumph of consumerism,” and criticizing them for softening the rough edges of knowledge by turning it into a consumer product.

Yet such chains continue to expand. Founded in 2014, Yanjiyou now has nearly 40 locations across the country — mostly in large cities — and plans to open another 60 by the end of 2019. A similar chain, Dayin Bookmall, has a branch not far from Luming’s new location, one of four in Shanghai. Dayin bills itself as “the bookstore where you can eat,” and the two-story location near Luming is right next to a subway station, ensuring good foot traffic. Open past midnight, it devotes much of its space to stationery stands, a dining area, and even a music studio where customers can record themselves reading after making a purchase of at least 70 yuan.

Customers seem to appreciate this format. Local university student Guo Fangxuanxuan praised Dayin’s layout, and the way people can just grab a book and sit down on the stairs to read. “It reminds me of what bookstores used to be like when I was a little girl,” she says.

Meanwhile, online retailers aren’t standing still either. The online market has continued to expand, eclipsing in-store sales for the first time in 2016, before growing by over 25 percent in 2017. And major online retailers have started opening physical storefronts as they look to branch into “new retail” — a term for integrated online-offline shopping ventures. Just a few steps from Luming, the 14-year-old Zhida Bookstore has reopened its doors, only now as an unmanned shop being run in close cooperation with Alibaba’s Tmall e-commerce platform.

Luming seems to have found a stable home, but many similar stores remain in precarious positions. Ultimately, in the face of new competition, Gu remains a purist. “When these bookstores choose what to put on their shelves, they focus more on how well the books sell and how much of a discount they can get from publishers. Quality comes second,” he says.

Gu’s attitude may strike a chord with some shoppers. Despite her appreciation of modern bookstores like Dayin, Guo, the student, continues to think independent bookstores have a role to play. “When it comes to discovering new books, I put my trust in places like Luming,” she says.

Editors: Lu Hua and Kilian O’Donnell.

(Header image: Customers browse for books at a Fangsuo bookstore in Qingdao, Shandong province, Aug. 31, 2016. VCG)