Metal Music With Chinese Characteristics

SHANGHAI — His face caked in dirt and blood, Cao Hongshun bellowed an epic song to the throng of long-haired men assembled before him. He sang of a general who abandoned his troops, a treacherous chancellor, a noble assassin that risked his life to save the dynasty, and how the defiant general rode back to rejoin his brethren on the front line.

The listeners didn’t understand a word of Cao’s performance — he was singing in Chinese, and most of them were Slovenian — but they continued head-banging and moshing nonetheless. The crowd swelled as festivalgoers clamored to watch the band clad in black-and-purple robes.

“That performance was significant for us. It gave us a huge boost of confidence, because it showed that audiences in Europe liked our music,” 32-year-old Cao tells Sixth Tone in a quiet Shanghai café.

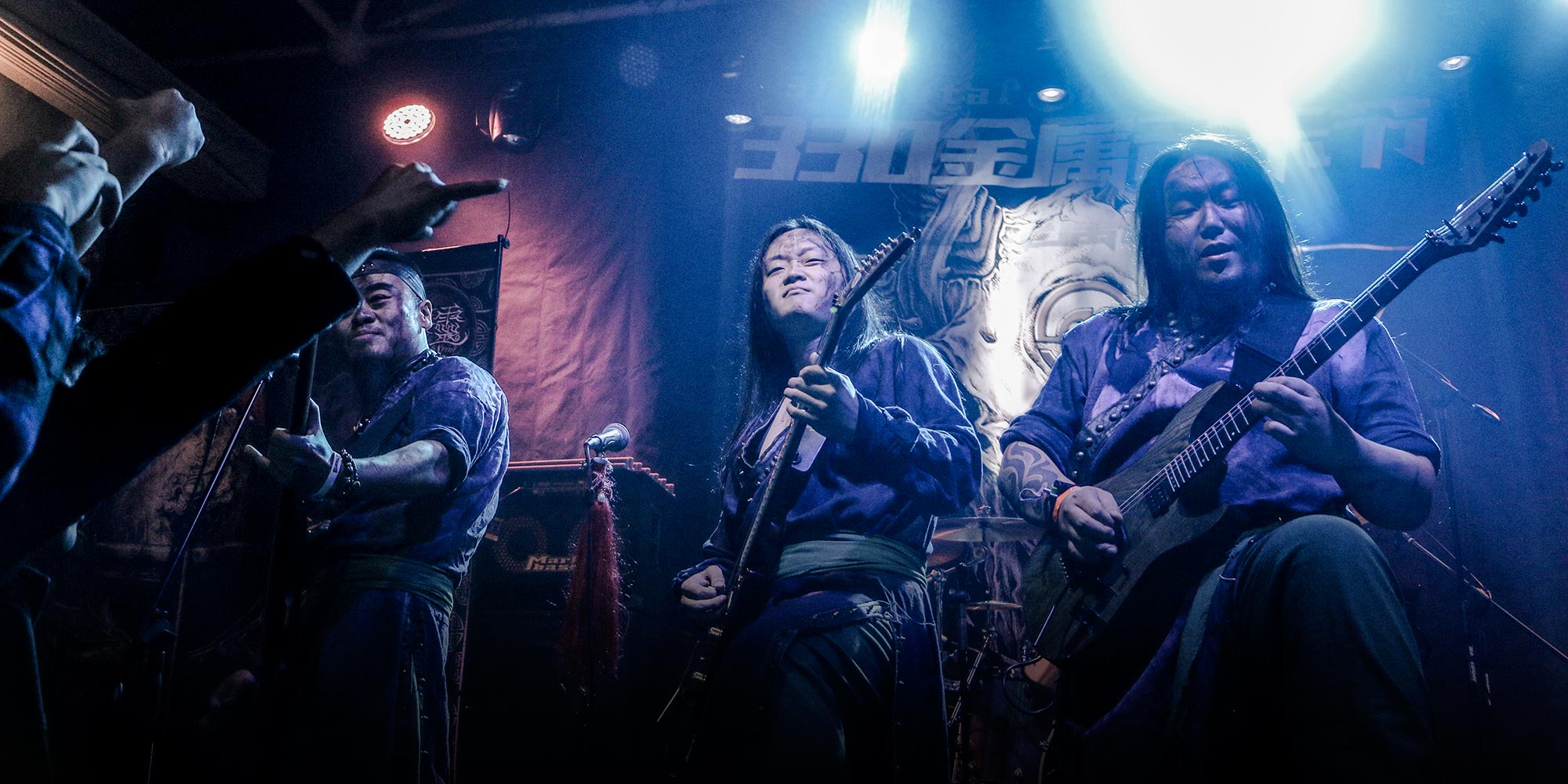

Cao, a tattooed metalhead who ties his long hair back for convenience, is the front man for Beijing-based metal band DreamSpirit. The performance in question was in July at MetalDays, an annual music festival in Slovenia that attracts big-league metal acts like Motörhead, Slayer, and Judas Priest. But DreamSpirit, one of China’s most successful metal bands, stands out from the rest: In addition to the standard guitar, bass, and drums, DreamSpirit blends traditional Chinese instruments like the two-stringed erhu and zither-like guzheng. Their lyrics tell tales of ancient China, and during live shows, the band wears warlike makeup and dresses in hanfu — a type of traditional Chinese garment.

The group is one of dozens of China-based metal bands that combine Western-style metal music with traditional Chinese culture. For some, it’s a natural mix: The epic tales of China’s past mesh well with the drama found in metal. But for others, the use of traditional Chinese clothing and narratives appears to be a cynical attempt to win over foreign audiences and make some extra money.

Cao traces his fascination with ancient culture back to his hometown of Tai’an in eastern Shandong province, which sits in the shadow of Mount Tai — a holy mountain that has attracted religious pilgrims for millennia. Compared with cosmopolitan Beijing, Shandong retains much of its traditional Chinese culture, says Cao. In 2005, Cao started DreamSpirit and began expressing an admiration for ancient civilization through his lyrics. “I feel like they were more impressive than we are: They were far more capable with their hands. These days, not so much. The only thing we can use is this,” says Cao, picking up his phone. “People have become dumb.” He thinks there are far more male role models in history than there are these days, adding: “Deep down, everyone wants to be a hero — especially boys.”

Despite their ancient-inspired lyrics, DreamSpirit didn’t start rocking out in hanfu until 2015, after the release of their first album. When Cao and his fellow bandmates were preparing for an international band competition, their agent suggested they don the traditional garb. Cao was against it at the time — he felt metal bands should stick to dark T-shirts and jeans — but the band’s outfits have since become a source of pride.

Cao dreams of getting signed by a foreign record label, but it’s highly competitive — with or without traditional outfits. He winces when he mentions that his next album will include some English-language songs to increase its marketability: The language was never his forte. But expanding their market may be necessary. While European metal fans come in all ages, China’s tend to peter out as they get older. Chinese metalheads also tend to gravitate toward darker forms of the music, so some have criticized DreamSpirit’s brand of power metal for being too modest and uplifting.

However, Wang Xiao — owner of the Beijing metal store Rock 666 that’s crammed with pentagram necklaces, CDs, cassette tapes, biker vests, and patches — feels that bands like DreamSpirit are on the rise. Other kindred examples include The Three Kingdom Generals, whose members dress up as characters from the classic Chinese historical novel, and Black Kirin, a death metal band that uses traditional instruments to evoke the horrors of the Nanjing Massacre. The practice of combining metal with ancient Chinese references has existed since the seminal 1988 heavy metal band Tang Dynasty, Wang says. “In the time of Tang Dynasty, most [metal musicians] thought that Western culture was better,” says Wang, who’s heralded as the “godfather of Chinese metal” by fellow metalheads for his creation of an influential metal-news portal. “But now, more and more Chinese have their own sense of pride: They think our culture is awesome, unique, and cool.”

Kaiser Kuo, a co-founder of Tang Dynasty, tells Sixth Tone that drawing on Chinese culture can help bands stand out from the rest. “It’s an obvious touchstone for a musical genre that’s aggressive and quite martial,” says Kuo over email. Western metal bands have long drawn from Western legends, and Chinese artists have plenty of their own material to do the same, he says, pointing to the hero-filled epic “Romance of the Three Kingdoms” or Louis Cha’s martial arts novels as examples.

But it can be hard to incorporate Chinese musical influences without sounding monotonous or tacky, says Kuo. What’s more, metal bands with Chinese characteristics can face criticism from Chinese metalheads who suspect the musicians do so just to win over foreign audiences, even though — as Kuo notes — that’s not the only way to gain success. This summer, Beijing metal band Die From Sorrow won the battle of the bands at Wacken, Germany — the biggest metal festival in the world — without any traditional Chinese elements. “Without naming names, I’ve certainly seen some bad efforts to incorporate recognizably Chinese elements … that I suspect had no commitment to it and were clearly doing it in the mistaken belief that it would be a marketing plus,” says Kuo.

That’s certainly the view of Liu Xuan, lead singer of Hellfire, a heavy metal band from the central city of Wuhan that wears black makeup during their performances and sings about the devil. “I think it’s because [the bands] hope it will be an easier way to get more foreigners to like them,” says Liu, a 31-year-old father who jokes that he’s actually 666 years old and a demon. Although he admires Tang Dynasty and doesn’t call out any band by name, Liu thinks many in the new wave of Chinese-style metal bands are not “real” metal. “Too many bands of this type have suddenly sprung up. I think they’ve probably never even heard of Black Sabbath … They’ve just made something new that doesn’t have heavy metal roots.”

But Bloodfire, the mysterious singer behind black-metal band Zuriaake, disagrees that there’s anything cynical about their love of traditional culture. During their atmospheric, fog-filled live performances, Zuriaake wear traditional pointed farmers’ hats that mask their faces. Lead singer Bloodfire shrieks in ancient Chinese as he slowly waves a white silk cloth — an item given to subordinates in ancient times, symbolizing that they should kill themselves. Although they were founded in 2007 and have toured internationally, they’ve never revealed their names to maintain their air of mystery.

After some persuasion, Bloodfire agrees to meet with Sixth Tone at a noisy Beijing bar for a chat over his favorite local craft beer, Jing-A. He’s in town to see his friends — or family, as he calls them — play shows. Beneath his infamous disguise is an eloquent and erudite individual with freckles and an intense gaze. Unlike many metalheads, the 35-year-old sports no tattoos — his father would have beaten him if he got one, he says — and keeps his thick, curly hair short. In contrast with his sinister onstage image, he’s fond of making deadpan jokes, before breaking into uproarious laughter.

Bloodfire came from a strict military family in coastal Shandong’s Jinan City, and listened to nothing but marches growing up. In the ’90s, he got his first taste of rock music from his older cousin, who would listen to Chinese rock star Dou Wei as they’d fall asleep. As a teenager, he used his lunch money to buy cassette tapes, and filled his belly by secretly raiding the fridge when he returned home at night. “For a period of time,” he pauses, turning mock-serious, “my parents thought we had mice!”

While in high school, Bloodfire was introduced to extreme metal by an older friend called DeathSphere. Around that time, he came across Swedish Viking metal band Bathory and began thinking: If there was Viking metal, couldn’t there also be Chinese metal? Scouring ancient Chinese literature, he stumbled upon the semi-mythological poetry of Qu Yuan, who died some 2,300 years ago. “We thought: ‘Isn’t this poetry metal?’” says Bloodfire. “There’s all kinds of profound and dark things within it. I think they’re the earliest examples of dark poetry in history.”

Bloodfire, DeathSphere, and their classmate Bloodsea drew inspiration from Qu and formed the band Zangshihu — meaning “corpses buried in a lake” — which later morphed into their English name “Zuriaake.” Once they settled on the name, all they needed to do was learn to play their instruments — which they did with the help of a pirated version of music software “Guitar Pro.”

Since then, Zuriaake has gained a following by using ancient styles to express modern-day realities and emotions. While some worry that traditional Chinese culture is vanishing in its “fast food culture,” Bloodfire says China’s culture is permanent, spanning unbroken from the past to the present.

Like Cao, he attributes his love of ancient culture to his place of origin. “Shandong culture is the culture of Confucius … it’s deep within my bones,” says Bloodfire. “Even though I listen to rock, even though I pursue freedom, even though I’ve been abroad and have been exposed to foreign culture … I can’t scrub this from my bones — it’s etched into my genes. The screams coming from my mouth are inevitably going to be Chinese-style melodies.”

Editor: Julia Hollingsworth.

(Header image: DreamSpirit performs at a concert during the 330 Metal Music Festival in Tai’an, Shandong province, Sept. 29, 2018. Courtesy of DreamSpirit)