How the South Manchuria Railway Shaped Modern China

This article is the first in a series on the South Manchuria Railway.

Today, Northeast China is known as the country’s Rust Belt. Overtaken economically by the coast, it’s weighed down by decaying, hollowed-out factories, lumbering state-owned enterprises, and a high unemployment rate. But 120 years ago, Northeast China was the emerging industrial heartland of East Asia, and its massive economic potential was enough to attract the interest of expansionists in both Russia and Japan.

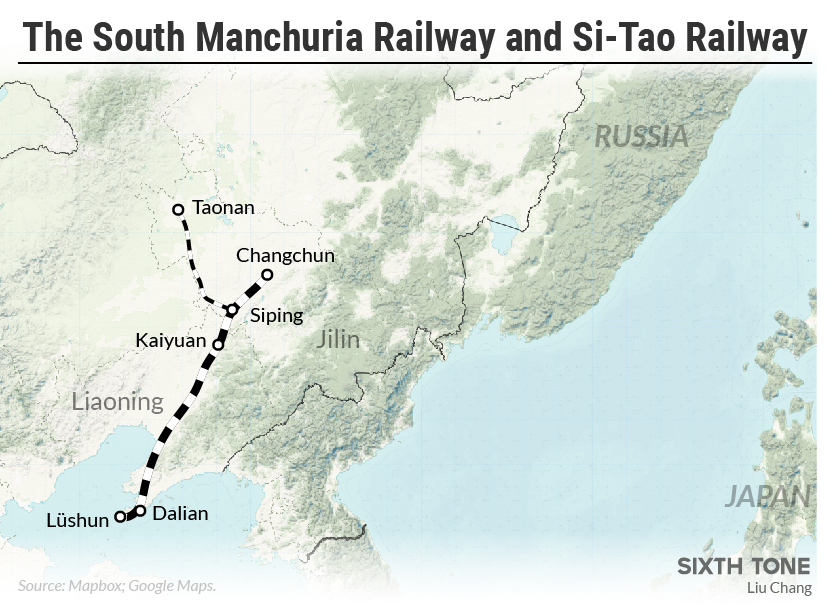

The Russians got there first. In 1897, they successfully pressured Qing dynasty officials into agreeing to the construction of a jointly funded but Russian-dominated railway across the northern part of the region. In May 2017, I traveled along this line — known as the Chinese Eastern Railway — from Manzhouli on the region’s western border with Russia to Suifenhe on its eastern border. But the Russians had greater ambitions in the region than a single rail line. Another line — the South Manchuria Railway — was built around the same time. Running from the city of Changchun in central Northeast China, it terminated at the then Russian-controlled harbor of Port Arthur in what is now Lüshun, in Dalian City.

While it may not be well-known today, the South Manchuria Railway played a crucial role in the history of the early 20th century. Then, China, Russia, and Japan struggled for control over this key economic corridor — and for dominance over Northeast Asia as a whole. Its construction enflamed the anti-Western sentiments that fueled 1899’s Boxer Rebellion and was a contributing factor in the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War in 1904. It was the center of Japan’s contentious postwar plans for expanding its economic and political influence in the region. And in 1931, it was the site of the Mukden Incident, a railway bombing the Japanese used as a pretext to invade and seize all of Northeast China, settling off a conflict with China that wouldn’t be resolved until 1945.

Located at the foot of Baiyu Mountain, Lüshun’s train station was the southern terminus of the South Manchuria Railway and, by extension, the southernmost train station in all of Northeast China. The first Lüshun station was built by the Russians in 1900 to serve Port Arthur, but by the time of their 1905 defeat in the Russo-Japanese War, they had already begun construction on a new station across the street. After the war, control over the region’s railways went to Japan, in the form of the so-called South Manchuria Railway Zone. The Japanese then proceeded to finish the mostly built station and repurpose the old one into a police station.

Since work on the station had largely been completed by the time of the Japanese victory, the 110-year-old Lüshun station hall features a number of classically Russian architectural flourishes, including green roof tiles that resemble fish scales and a bell tower. One of the few surviving indicators of Japanese rule is the roof over the train platform, which consists of sheets of tarpaulin pulled over a wooden structure once used to house Japanese soldiers.

Trains stopped running to and from Lüshun Station in 2014, though the ticket office and waiting room remain open. People still sometimes stop by: the occasional tourist in search of holiday album-fodder and a few aged locals looking to reminisce.

Head north 500 kilometers and you’ll come to Kaiyuan. The Russians gained control of the area in 1902, and in 1903 they built a simple train station in the town. In 1905, the area was occupied by the Japanese, who built a new, two-story station in 1929. After they gained control of the region’s rail network, the Japanese exploited it by establishing commercial districts in the vicinity of each stop. Today, although the region may be in decline, the station remains in remarkable condition for its age — its white accents have even been kept crisp and even.

Slightly farther north, the city of Siping is another example of the economic impact the railway has had on the region. Prior to the line’s construction, the area where Siping now sits was essentially empty wilderness. The above-mentioned Japanese economic policy helped develop the area’s commerce — leading to the creation of Siping’s first urban district — but the Japanese weren’t the only ones trying to take advantage of the region’s economic potential.

In 1916, China built the Si-Tao Railway, which stretched from Siping over 300 kilometers northwest to the town of Taonan. In Siping itself, the Chinese authorities established their own competing economic zone. Initially, both the Japanese and Chinese shared the use of the Siping station — known to locals as North Station — but the Japanese-run South Manchuria line eventually moved to a new building of its own. Thus, for a short time almost a century ago, Siping had two train stations: one Chinese, and the other Japanese.

This uneasy state of affairs continued until 1931, when the Japanese invaded Northeast China and seized control of the entire region. The day after the Mukden Incident, the Japanese garrison in Siping attempted to occupy the city. When they moved to seize the Chinese station, however, they found that a small Chinese force had fortified three parallel checkpoints controlling access to the building — collectively known as Qiazimen. This force was able to hold off the Japanese for three days, only surrendering after the arrival of Japanese field troops.

Today, the only sign of this struggle — one of the first battles in China’s 14-year-long war against Japan — is a single commemorative plaque. The Qiazimen checkpoints themselves are thoroughly dilapidated; their windows have been sealed with red bricks, red roof tiles lie strewn about, and their walls are spiderwebbed with cracks. It’s a shame. In 1931, China was rife with internal conflict, and the skirmishes at Qiazimen were one of the very few points where the Japanese invasion force encountered any resistance. The site should stand testament to the courage shown by a few brave souls in the face of inevitable defeat, not the area’s deteriorating economic fortunes.

The South Manchuria Railway is more than just a railway: For half a century, it was the fulcrum upon which the fate of East Asia rested. In other words, if you want to understand the historical scars that continue to inform the relationship between China, Russia, and Japan, you could do worse than first catching a train.

Translator: Lewis Wright; editors: Wu Haiyun and Kilian O’Donnell.

(Header image: An exterior view of the Lüshun train station in Dalian, Liaoning province, May 17, 2018. Courtesy of Ma Te)