A Family, a Flight, a Fight to Get Home

This week, Sixth Tone will publish accounts from Chinese who were living, working, or traveling overseas when the pandemic hit, and their subsequent journeys in search of safe harbor. Part one can be found here. Part three will be published Thursday.

On March 18, my mother, husband, 7-month-old son Wilmar, and I arrived at Los Angeles International Airport, ready to return home to Shanghai.

Back in late January, we watched with alarm from the United States as COVID-19 spread across China. After three major U.S. carriers canceled their flights between the two countries, on Jan. 31 the American government announced it would bar entry to most foreign nationals with recent China travel histories and start instituting limited quarantines.

Although we’re both based in Shanghai, my American husband works for a company with offices in that city and in California, and we decided to extend our stateside stay by a month. By late February, however, the situation in China was showing signs of stabilizing, just as the pandemic had begun to take root in the U.S. We knew there were risks involved, but after the American Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warned that the spread of the coronavirus in the U.S. was all but certain, we decided it was time to go back. On March 13, U.S. President Donald Trump declared a national emergency; on the day of our flight, New York state recorded more than 1,000 new cases.

As a journalist, I’ve reported on environmental issues from Congo during the Ebola crisis in 2016 and toured black markets in Laos. Since becoming a mother, however, that fearlessness has seemingly vanished. The week before our flight, I kept waking up in the middle of the night to look at my baby sleeping beside me. I wondered how we could possibly keep him safe.

Most of the other passengers on our flight were international students, eager to get home. A handful of them were dressed in protective gowns, safety goggles, and masks. Once on board, they barely moved except to lower their masks to take a sip of water.

We arrived at the Shanghai Pudong International Airport some 20 hours later, on March 19, local time. Two days earlier, the city had begun treating the U.S. as a “key” country. Whereas travelers from low-risk countries could go home and self-quarantine after a medical check, those arriving from moderate- or high-risk countries had to undergo more tests to see if they would be sent to a hospital or be quarantined. A week later, with the pandemic spreading everywhere, those quarantines would become mandatory for all international arrivals to the city.

Coming from a high-risk country, we knew that, starting from the moment we entered the country, we would be kept physically isolated from the outside world until the authorities could be sure we weren’t infected.

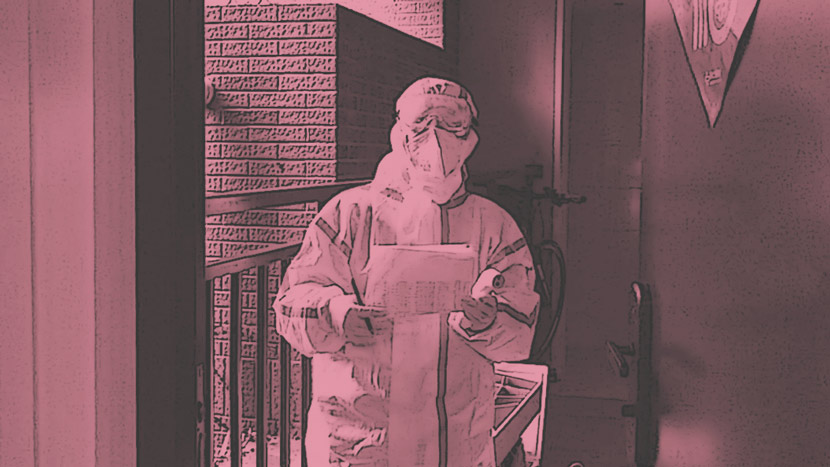

As soon as we landed, health officials in hazmat suits came on board. “Elderly passengers or those with children can disembark first,” one of them said. That was music to my ears, as my son had been fussing and bouncing on my leg.

After disembarking, we were asked to fill out health declaration forms. An official asked us about the places we had visited in the last 14 days, down to the states and cities, while another took our temperatures. After leaving customs, passengers were separated according to our residential neighborhood and directed onto a dedicated bus, which shuttled us to a local COVID-19 testing point.

Five hours after landing in Shanghai, we reached our testing site, which was located at the southeastern tip of the city. The staff were dressed in white hazmat suits that made it impossible to see their faces, but they had written their names — or in some cases, humorous nicknames — on their gear. Wilmar peered out curiously from my arms at what felt like a scene straight out of the “Resident Evil” franchise. I was glad he didn’t cry.

The testing site was situated in the spacious courtyard of a hotel, separated from the neighboring buildings with fences and iron gates. The test was a simple oral swab, but it was a challenge to get Wilmar to cooperate. He didn’t understand what was happening, and the doctor had to keep opening her mouth wide until Wilmar learned to mimic her.

We were told that the sample results would take at least 12 hours. Drained by our long flight and the quarantine, we were happy to be able to rest at the hotel. On our second night, however, the hotel phone suddenly rang.

“Your car’s waiting outside,” the caller said. “Hurry up and come down.”

Our oral swab had come back negative. It felt like a huge burden had been lifted off our shoulders. My husband and I had tried to make plans in case one of us fell sick, but the discussion always petered out as soon as our son came up.

Fifty hours had passed since we had boarded our flight at LAX, but we could finally return home. This was without a doubt the longest, most stressful homeward journey I have ever experienced.

The neighborhood committee, police, and doctors from the community hospital were waiting by the gates of our neighborhood. The doctor took our temperature yet again, while the police and the neighborhood committee took down our personal information. They told us we would need to quarantine ourselves at home. We would not be allowed to go outside for 14 days. In addition to reporting our temperatures to the community hospital every day, they would also conduct spot checks. Property management would take care of our shopping and trash.

The next day, the neighborhood committee installed a black box outside our door. It was a sensor. If we opened our door, it would send a notification to their phones.

Although my husband called these measures “extreme” and “crazy,” he wasn’t complaining. Instead, he has repeatedly told his friends elsewhere that they’re exactly why he trusts China’s ability to contain the virus. We’re both grateful for the people who’ve worked so tirelessly to make it all possible: We finally don’t have to worry about Wilmar’s health.

Instead we worry about our friends and family in the U.S. and Europe, where the situation has deteriorated. It wasn’t that long ago that we were mailing masks from the U.S. to our friends in China. Now my husband is mailing them the other way.

When we first arrived in Shanghai, he called his younger brother and sister-in-law, who live in New York City. His sister-in-law works at a hospital there and was about to be assigned to the ICU. The staff at her hospital had been told they would have to reuse their masks and other protective gear.

Their child just turned 1. I can’t even begin to imagine the stress they’re under.

All I can do is hope things get better soon.

Translator: Katherine Tse; editors: Wu Haiyun and Kilian O’Donnell.

(Header image: A girl rests at an airport in Phuket, Thailand, March 22, 2020. Mladen Antonov/AFP via Xinhua)