How a Rugged COVID-19 Recovery Risks Over 100 Million Jobs

Sun Xiao can tell you off the top of her head how many days have passed since Jan. 23. That’s the date the Beijing tour guide became “de facto unemployed,” and she has counted each of the 65 days since.

Following the lockdown Jan. 23 of central China’s Wuhan metropolis to slow the spread of COVID-19, China hit the pause button for the travel industry, suspending all domestic tour services and related flight and hotel sales and halting international tours four days later. Sun is one of almost 30 million people affected at more than 40,000 travel companies across China.

Now, as the outbreak slows in China, Sun and her colleagues in the industry wait anxiously for business to resume. Since early March, some scenic sites outside central Hubei province, where the coronavirus first emerged in China, have reopened for tourists, but travel agencies have largely remained closed as the pandemic now accelerates abroad.

The plight of Sun and others in the travel industry shows how hard it will be for the world’s second-largest economy to get back to work. The coronavirus outbreak put almost all business activities on hold since the Lunar New Year holiday in late January. Those stuck out of work also include millions of people in catering, accommodations, housekeeping services, manufacturing, and construction.

The pandemic delivered a heavy blow to a Chinese economy that was already struggling to manage downward pressures and a weakening job market. Economists widely project that the economy is contracting in the first quarter, dragging projected 2020 GDP growth down to 4% or even lower. Based on 2018 and 2019 data, every 1 percentage point of GDP growth affects more than 2 million jobs.

China’s official unemployment rate jumped to a record 6.2% in February from 5.3% in January. During the first two months of 2020, 1.08 million new jobs were added in China’s urban areas, down 660,000 from the same period last year.

The February surge in unemployment reflects massive business suspensions and workforce cuts, according to Zhang Yi, a senior official at the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). Industries including retail, catering, accommodations, transportation, logistics, and entertainment have experienced the biggest job losses, Zhang said.

At two Cabinet meetings in March, Premier Li Keqiang repeatedly called for efforts to stabilize the job market.

“As long as employment is stable this year, it will not be a big deal if the economic growth rate is higher or lower,” Li said.

“It is likely a signal,” said Zhang Yu, chief macroeconomy analyst at Huachuang Securities. Compared with efforts to keep economic growth at a certain level amid external uncertainties, maintaining a stable job market is a more pragmatic way to benefit the economy in the long run, Zhang said.

The pandemic brings thornier challenges and more lasting impacts to China’s labor market than the 2008 financial crisis, when factories laid off workers as business declined. Although early domestic measures to contain the disease hit the job market by halting production and restricting people’s mobility, the ensuing outbreak in the rest of the world is eroding external demand and weighing on the workshop of the world’s efforts to recover. The global supply chain is at risk.

Li Zhong, China’s vice minister of human resources and social security, said March 19 that while some companies are still struggling to hire enough workers, an increasing number of others are facing the threat of losing orders, forcing production lines to stay idle.

Meanwhile, the services sector that has created the most new jobs in recent years is struggling to resume business amid lingering contagion risks and consumers’ increasing hesitation to spend.

Compounding the challenge is that the structure of China’s job market has changed profoundly since the 2008 financial crisis. The number of migrant workers — who are mainly employed in construction and manufacturing — has declined sharply over the past 10 years as the older generation retired. In 2019, 2.4 million new migrant workers entered the job market, down from 10 million each year a decade ago.

In their place, new college graduates have become the major category of new entrants in the job market. In 2020, about 8.7 million students will graduate from colleges. Most of them will need a job and prefer occupations in industries other than construction or manufacturing.

Consequently, policymakers can’t just flip a switch to spur hiring in labor-intensive sectors such as property and infrastructure as they could a dozen years ago.

Leaders have turned to more sophisticated policy measures to address the evolution of the job market. On March 20, the State Council, China’s Cabinet, issued a set of guidelines to promote business resumption and job market recovery, outlining policies to support the return of migrant workers and create more occupations for them, increase state companies’ recruitment of new graduates, expand enrollment of postgraduate students, and draft more graduates for military service. More supportive packages will also be offered to help people who lost jobs and ensure their basic incomes.

Those guidelines followed a series of measures by central and local governments since late January to help businesses stay afloat. The steps include policies to reduce employers’ social welfare contributions and lower business costs. The policies would save businesses more than 500 billion yuan ($70.5 billion) this year, officials said.

In response to the job market challenges, the central government will step up policies to support companies, especially small- and mid-sized enterprises, to maintain stable business operations and employment, said Mao Shengyong, an NBS spokesman. Mao said he expects unemployment to decline in the second half as the economy revives.

Business on Pause

The COVID-19 outbreak forced businesses across China to extend the normal weeklong Lunar New Year holiday through February as people stayed home to avoid contagion. In normal years, companies resume operations about a week after the holiday.

Official data showed that just 60% of migrant workers who returned home for the holiday were back to work as of March 7. The rate rose to 80% by March 19. Many companies in labor-intensive industries had trouble filling factory floors until earlier this month as workers in virus-hit regions such as Hubei and Henan provinces were barred from traveling. Meanwhile, many employers that managed to round up enough workers have since cut hours because of slowing demand and concerns about lingering risks of infection.

Overall working hours in February totaled 40.2 hours a week — 6.5 hours less than in the previous month, NBS data showed. In the first two months this year, China’s total electricity consumption declined 8.2% year-over-year while industrial contribution to domestic gross product fell 13.5%.

The catering industry reported a 43% revenue drop in the first two months from a year ago. Accommodations and housekeeping industry revenue nosedived by more than 75% in February alone, official data showed.

The freezing-up of business quickly translated to the labor market. A survey by Ernst & Young in late February found that 25.5% of companies said they furloughed or laid off workers or cut wages.

Companies also reduced recruitment during the outbreak, although February is traditionally the high season for job-hunting. A joint survey by Peking University and recruitment site Zhaopin.com found that new job listings in the first two months this year dropped 32.4% from a year ago. Entertainment, services, telecom, and internet were among the industries affected the most.

As the outbreak wanes and travel restrictions ease nationwide, businesses since early March have accelerated the pace of resuming operations. Data from the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) showed that as of March 13, 95% of China’s industrial enterprises — excluding those in Hubei — resumed operation with an average 80% of their workers.

But figures for the services sector were held down. As of March 26, the resumption rate for catering companies was 80%, for accommodations 60%, and for housekeeping businesses 40%, according to the Ministry of Commerce. Close personal contact, weakening consumer confidence, and reliance on a massive labor force are factors hindering the service sector’s recovery after the long pause, said Zhu Xiaoliang, a senior official at the ministry.

Travel’s Grim Outlook

The grim outlook of the travel industry threatens the living of 100 million people. In 2019, the travel industry hired more than 28 million people, with nearly 80 million others working in related businesses. That involved almost 10% of China’s total employment. The industry contributed 10.9 trillion yuan to China’s GDP last year, or 11% of the total.

As parks closed and flights were grounded, China’s travel industry is expected to lose 1.18 trillion yuan in revenue this year, a 20.6% drop from last year, according to Beijing-based China Tourism Academy.

Although experts said tourism companies should keep their workforces ready for a resumption of business, many enterprises face pressures to stay afloat. Companies have been closed for too long and lost too much revenue, said a person from a large state-owned travel agency in the southwestern Yunnan province. The company has stopped paying employees and has let people go, he said.

“We have no choice but to lay people off in order to survive,” said another travel service provider in Beijing.

The fallout of the travel industry freeze also affects hotel operators. American luxury hotel chain Marriott International CEO Arne Sorenson said March 18 that the company’s business plunged 90% in China and the slump continued elsewhere around the world as the virus spread.

According to Sorenson, the COVID-19 pandemic has had a larger financial impact on Marriott than 9/11 and the financial crisis combined.

Restaurants also suffered and consider recovery far-off. Song Hongyang, a restaurant owner in southern city Shenzhen, made the hard decision to close his business and let go of more than 30 employees March 1. His restaurant, in an industrial area, has had almost no business since February but more than 400,000 yuan of monthly costs for rent, utilities, and salaries, he said.

“Every day I kept it running, I lost money,” Song said.

A survey by the China Hotel Association (CHA) in late February found that nearly half of the 309 catering companies surveyed had plans to close part of their outlets. Meanwhile, 56% of the companies said they would lay off some employees.

A catering industry source in the southern Guangdong province said that although earlier supportive policies cut some costs for restaurant operators, the industry needs more incentives to bolster incomes.

The CHA forecast that if the pandemic could be successfully controlled by the end of March, the losses to China’s catering industry would be around 1.3 trillion yuan this year. But the industry will revive as business resumes in the second quarter and starts a stronger rebound in following quarters.

Lingering Risks

While most workers in the services sectors are still waiting to return to their jobs, those in factories face new troubles.

“At first it was clients in Europe, Japan, and South Korea that cancelled their orders; now American clients also started cancellations,” said an executive of a Jiangsu textile company. The factory has experienced a 70% decline in orders from the same time last year, the executive said.

As COVID-19 continues to rage across the globe, more countries have turned to drastic measures to suspend businesses and lock down cities.

Overseas clients have been cancelling orders since early March, and the pace is increasing rapidly, said Huang Wei, vice president of the Shanghai branch of garment exporter Li & Fung Ltd.

A jewelry company manager in Yiwu, eastern Zhejiang province, said about 5% of the company’s orders have been dropped over the past two weeks. March is usually the busy season, but this year there are almost no new orders, said the manager, who said he expects a 30% to 40% drop in orders this year.

As business cools, manufacturers are considering reductions in pay or workforce to save money. A survey by Zhaopin.com found that about one-third of companies said they have layoff plans.

A dramatic decline in foreign demand amid the pandemic will pose great challenges to China’s export industry, threatening the jobs of nearly 60 million people, said Lu Ting, chief China economist at Nomura International Ltd. in Hong Kong.

The COVID-19 outbreak is squeezing China’s job market from both the supply and the demand end, said Lu, who suggested greater policy support to stabilize the market. Policies should focus on easing the strains of small businesses to encourage resumption as well as measures to prevent company and household default, Lu said.

Policymakers could consider using targeted quantitative easing to increase the money supply or special government bonds to support companies and households hit hard by the pandemic to counter the economic fallout and support a recovery of consumption, Lu said.

This is an original article written by Yu Hairong, Qian Tong, Ye Zhanqi, Shen Xiyue, and Han Wei of Caixin Global, with contributions from Yuan Ruiyang, Liu Shuangshuang, and Zhang Erchi. It has been republished with permission. The article can be found on Caixin’s website here.

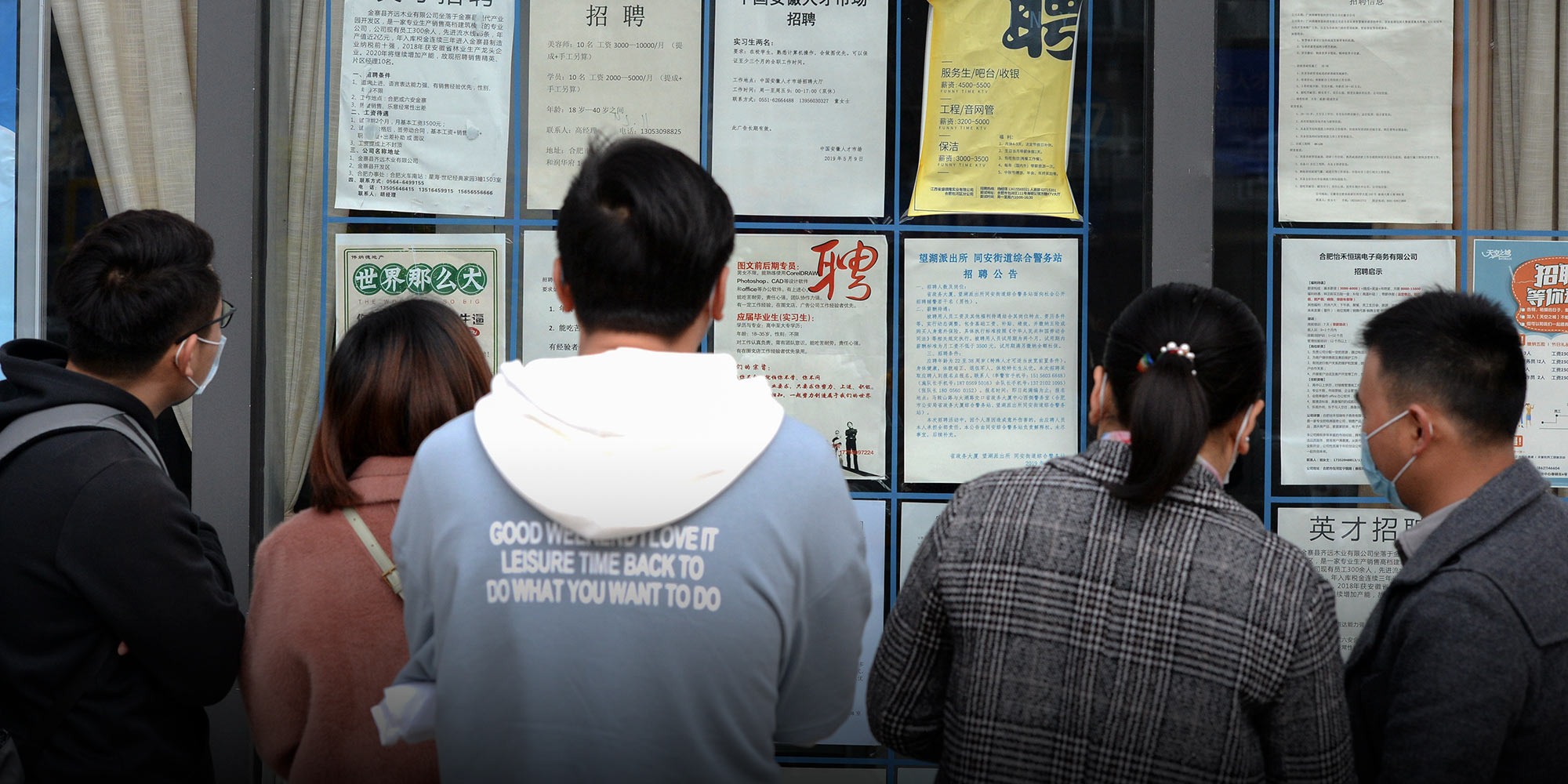

(Header image: People look at job postings at a job fair in Hefei, Anhui province, March 28, 2020. Huang Bohan via Xinhua)