Wuhan Nurse’s Death Highlights a Profession in Crisis

After finishing her rounds one morning in late July, a nurse at a major Wuhan hospital plummeted to her death from the 13th floor of the internal medicine building.

While the circumstances remain unclear, police later said Zhang Yanwan’s death required “evaluation by specialized public mental health departments” — a strong indication that the married mother-of-one likely killed herself, in a country where suicide rulings are rare.

The 28-year-old’s death shocked her family, friends, and colleagues, many of whom believe the months she spent fighting the central Chinese city’s devastating coronavirus outbreak and arguing with hospital managers over working conditions played a part in her demise. Her former employer, Wuhan Union Hospital, has said little publicly about what happened.

The incident has also brought to boil a simmering debate about the plight of China’s underpaid, overworked nurses, some of whom are now grappling with the psychological fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has exacerbated the effect of years of high stress and exhaustion.

But those debates are scant consolation to a bereft family searching for answers after the sudden loss of their daughter. Zhang’s father, who requested anonymity out of fear of retaliation from the authorities, told financial outlet Caixin he cannot bear to live among his daughter’s possessions and has moved out of the family home to a hotel opposite the hospital.

“I’m so sad, no matter where I go or what I do,” he said.

Outspoken Streak

Interviewed by Caixin, several of Zhang’s friends and relatives described her death as unexpected and hard to understand.

She was a cheerful, outgoing person, a loving parent to a 1-year-old son and a devoted nurse, her father said.

But colleagues at Wuhan Union, where Zhang worked for five years, said she also had an outspoken streak that grated on hospital management earlier this year.

Zhang was one of the hospital’s frontline COVID-19 responders when the city’s deadly outbreak took hold in January. As a key medical facility located a few miles from the food market at the center of the country’s epidemic, Wuhan Union was rapidly overwhelmed with hundreds of patients.

Amid chronic shortages of personal protective equipment, staff at the hospital soon started getting sick. Health officials first reported COVID-19 cases among Wuhan Union employees on Jan. 20, and by the end of the outbreak some 174 workers had caught the disease, accounting for more than one-quarter of all infections among medical staff in the surrounding district.

Zhang’s father said the hospital’s failure to protect staff left his daughter feeling “dissatisfied.” In late January, Zhang posted two messages on social media calling on her colleagues to resign if the hospital’s director of nursing stayed in her post.

“I’m willing to be a martyr constantly struggling on the front lines,” Zhang wrote. “But I’d prefer to be a martyr with bullets in my gun and body armor, not a human shield!”

Zhang tendered her resignation days later, but hospital officials refused to accept it owing to “special circumstances” and disciplined her for the posts, her father said.

Department’s Grudge

What happened in the months between the outbreak and Zhang’s death remains uncertain.

After Wuhan’s crisis eased in March, Zhang returned to her previous duties on Wuhan Union’s cardiology ward. On the surface, she seemed well: The hospital honored her for her frontline work, and she appeared “happy and sunny” when she chatted with her parents on social app WeChat two days before she died, her father said.

But there were also signs Zhang was under strain. Her father alleges she was bullied by her head nurse, who summarily reassigned her to the intensive care unit for “training” purposes and ordered her to write repeated self-criticisms in which she made groveling apologies to the nursing department for her social media posts.

One of Zhang’s ward colleagues said “conflict” existed between Zhang and the nursing department, but declined to comment further.

Zhang died on July 29. Police ruled out foul play, but an investigation is ongoing.

Wuhan Union made one short public statement in response to Zhang’s death, saying it was “actively cooperating with the family and the relevant authorities to handle the aftermath of this incident.” Multiple interview requests by Caixin to senior hospital officials went unanswered.

Hospital staff on duty at the time of Zhang’s death mostly refused Caixin’s interview requests out of fear of repercussions from their employer. Those who spoke did so on condition of anonymity.

Zhang’s family told Caixin they have been denied extensive meetings with hospital officials about their daughter’s death. They continue to push for the truth to come to light.

Overworked, Underpaid, Quitting

Zhang’s death refocused attention on China’s understaffed, overworked nursing sector.

Despite government efforts to recruit more and higher-educated nurses, the country suffers from persistent shortages. In 2018, the country counted 2.94 nurses per 1,000 people, significantly below its 2020 aim of 3.14 per 1,000 and only around one-third of the ratio in the European Union. China’s proportion of nurses to doctors also remains lower than targeted.

Many nurses in China complain of low pay. According to a national survey conducted by the government-linked China Social Welfare Foundation, more than three-quarters of nurses earn less than 5,000 yuan ($738) per month. For some, contractual arrangements that partly distribute pay according to performance force real salaries even lower.

Long hours are part of the job. According to another national survey published in 2016, half of China’s nurses work longer than eight hours per day, 24% more than in 2010. Just under half work more than seven night shifts per month, an increase of 13% over the same period.

Many nurses say they are given excessive clerical or administrative tasks, such as writing incident reports, which add to their workloads and distract them from caring for patients. “Since my first day on the job, I’ve never, on any shift, eaten a full meal or gone to the toilet during work hours, out of fear something will happen to my patients,” said one nurse at Wuhan Union.

Consequently, nurses are leaving the industry in droves. The outflow, combined with many hospitals’ reluctance to spend money on nursing, heightens the burden on those who stay.

“Chinese nursing desperately needs excellent people with rich, specialist knowledge who can make clinical decisions about complex acute and chronic health issues and combine their education, research, and individual nursing skills to address them,” wrote Jiang Yan, the head of nursing at Sichuan University West China Hospital, in an article published in January in the industry journal Chinese Nursing Management.

Systemic Burnout

Chinese nurses commonly report work-related mental health complaints including high stress, low mood, and exhaustion.

Some experience verbal or physical confrontations with patients, a relatively common occurrence in China’s health care sector.

A number of studies with limited sample sizes indicate that mental health issues may be rife in China’s nursing sector. In January, an industry magazine published a survey in which 31% of nurses at eight hospitals in Beijing said they suffered “moderate” psychological abuse at work, most commonly verbal bullying or teasing from more senior colleagues.

Occupational burnout is another problem. In a 2018 study, nearly 3,500 nurses at six large hospitals in eastern China’s Anhui province said they mainly experienced emotional distress due to exhaustion at work.

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated many of these issues. A study published earlier this year by the peer-reviewed American Journal of Psychiatry found that nearly half of more than 2,000 frontline and non-frontline medical workers at key hospitals in Wuhan experienced depression during the peak of the country’s epidemic, while 41% experienced anxiety and 62% felt elevated stress.

Experts told Caixin there was a danger that some nurses may continue to experience symptoms of post-traumatic stress long after the outbreak had eased.

Despite calls in recent years for the government to speed up health care reform and expand legislation to better support nursing, many nurses interviewed by Caixin said little had changed in their hospitals.

Pressure to please “too many” high-status groups, like doctors and emergency room staff, means hospitals often push nurses’ concerns to the back of the line, said Liao Xinbo, the former head of the health bureau of South China’s Guangdong province, adding that China should research how to provide more personalized management and address the power wielded by more specialized groups of medical workers.

“They endure extremely high stress both professionally and psychologically,” Liao said.

This is an original article written by Zhao Jinchao, Yan Ge, and Matthew Walsh of Caixin Global. It has been republished with permission. The article can be found on Caixin’s website here.

In China, the Beijing Suicide Research and Prevention Center can be reached for free at 800-810-1117 or 010-8295-1332. In the United States, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline can be reached for free at 1-800-273-8255. A more complete list of prevention services by country can be found here.

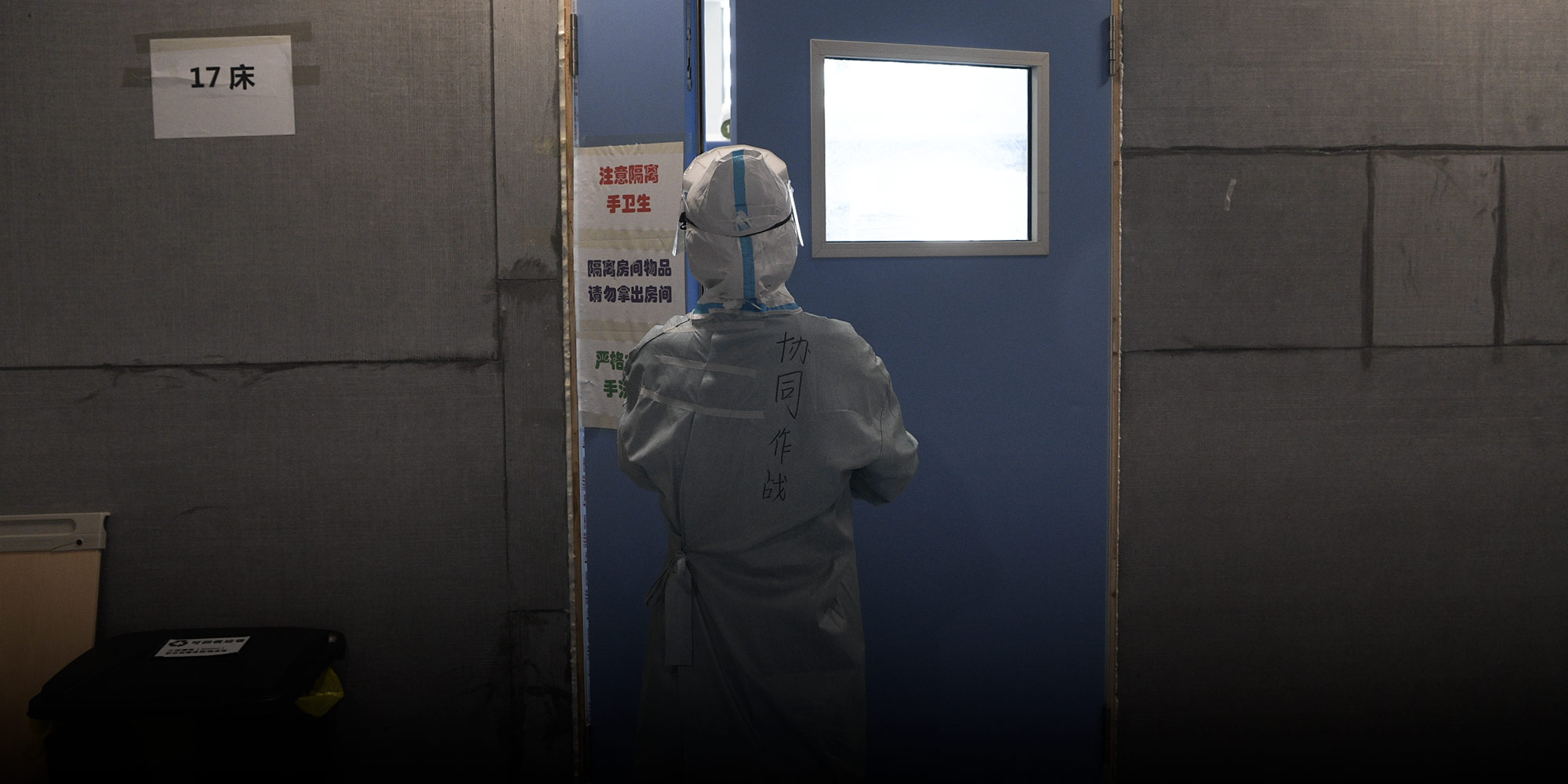

(Header image: A medical worker closes a door in the inpatient area of Wuhan Union Hospital in Wuhan, Hubei province, April 12, 2020. Chen Hao/People Visual)