Rural E-Commerce Programs Can Work. So Why Do Some Fail?

In the span of just 40 years, China’s place in the public imagination has changed from rural backwater to a land of massive, gleaming cities and high-tech innovation. Yet there were still more than half a billion people living in the country’s rural hinterlands in 2019, many of whom have been left behind by an increasingly digitized economy. At its core, their dilemma is twofold: They can’t buy and they can’t sell. That is to say, there’s no outlet for their farm produce or their labor, and they don’t have the access to the high-quality, cheap industrial products ubiquitous in urban areas.

This persistent urban-rural gap — and the question of how to keep the countryside from becoming a casualty of urbanization — has frustrated policymakers for years. More recently, the government has placed its hopes on “rural e-commerce” as a viable solution to this conundrum. In 2015, in the interests of “promoting the advancement of agriculture, stimulating rural development, and boosting farmers’ revenue,” the central government made rural e-commerce a key policy focus, and related initiatives have since been rolled out nationwide, especially in impoverished areas.

These efforts have already had a profound impact on the countryside. In his survey of an e-commerce-focused “Taobao village” in the eastern province of Jiangsu, the anthropologist Zhou Daming noted that the internet and improved logistical networks have greatly reduced geographical and temporal constraints, allowing villagers to develop trading networks across increasingly large and diverse regions and giving them a foothold in national or even global markets. In some areas, agglomerations of rural e-commerce businesses have even accelerated the transformation of villages into townships, and townships into cities.

Rural e-commerce has not been successful everywhere, however. To gain a more nuanced understanding of why, it may be useful to break down one particular failed experiment to see what it can tell us about the current state of rural e-commerce and the rural-urban market system.

Gumu County — I have changed all place and company names to protect the identities of my research participants — is located in a rural part of North China known for producing chestnuts. In line with the provincial government’s stated aim of achieving “province-wide coverage of rural e-commerce,” Gumu selected a relatively new e-commerce company, Taole, to set up a rural e-commerce public service center in the county.

Taole proceeded to survey small shops and supermarkets across the county’s 290 administrative villages, choosing a business from each village to become one of their “offline service stations.” These offline service stations received installations of equipment that allowed villagers to place and receive orders. They also took in villagers’ agricultural products, which were then transported to the public service center and sold on Taole’s unified trading platform.

Throughout the process, the Gumu County government mobilized administrative resources in its villages and townships to ensure the program’s success. It also rolled out subsidies totaling millions of yuan to cover rent, construction, and equipment costs. Thanks in part to this investment, service stations had been opened in all 290 villages by the end of 2016.

But the stations quickly ran into difficulties. As part of my Ph.D. research, I took an internship with Taole from July-September 2016. Publicly, the company maintained it processed 9.35 million yuan (then roughly $1.4 million) in transactions from January to August of that year; the internal data I had access to showed that in August — harvest season — the company processed just 213,000 yuan in transactions. When I interviewed a staff member at the company in October of the following year, they told me that transactions had continued to fall consistently from that point on, with sales functionally grinding to a halt from May 2017 and on. Taole soon began cutting jobs before pulling out of Gumu altogether in 2018. The project, once so promising, had come to nothing.

What happened? Let’s start by taking a closer look at four interrelated problems. First, local officials placed too much emphasis on numbers and not enough on solving practical issues. According to the plan, all 290 villages in Gumu County were supposed to open service stations, but at the time, some small villages didn’t even have a single shop in which to host the station. Rather than include them in the service areas of nearby villages, they received temporary stations that were set up to meet the administrative requirements of the rollout. The owners of these stations were either village cadres or villagers mobilized by the cadres, and their lack of commercial managerial experience was evident.

Second, many villages lacked the infrastructure and technical know-how needed to successfully engage in e-commerce. The overlapping mountain ranges and intersecting ravines of Gumu County — to say nothing of its lack of refrigerated containers and other storage facilities — vastly increased the costs of ensuring produce arrived fresh at its destination.

In addition to physical transportation costs, information technology also posed a hurdle. Although broadband and mobile networks are generally widely available in China, several of the service stations in Gumu County had poor reception, and many station owners were reluctant to pay extra for broadband, turning their stations into little more than glorified showrooms.

Third, at least in Gumu, the reliance on public-private partnerships in rural e-commerce initiatives caused problems when it came to balancing profit against social benefit. Take Taole’s approach to marketing the county’s main cash crop, chestnuts, for example. During the autumn harvest, Taole did not actually buy any chestnuts — rather, they merely selected two villages to do a preliminary survey, and then began advertising their chestnuts at the price of 32 yuan per kilogram on their platform, with no additional promotion. Unsurprisingly, the ad went unnoticed and hardly any chestnuts were sold.

Given how uncertain the e-commerce market was for Gumu chestnuts in the first place, it’s understandable that Taole might prefer to avoid risks by soft-pedaling the rollout. But more than the farm-to-consumer side of the business struggled: The company also made little effort to sell villagers the cheap industrial goods they needed. Taole and other e-commerce firms carry out frequent promotional sales and other activities, but few have the connections with manufacturers necessary to obtain their goods at truly competitive costs. Villagers, already suspicious of e-commerce, thus became all the more distrustful when they discovered that prices in Taole’s sales were actually higher than those offered by traditional wholesalers.

Finally, e-commerce platforms’ approach of “pay now, deliver later” was at odds with the consumption practices of local farmers. During my stint as an intern, I often heard complaints like, “I often only discover I don’t have the right seasoning when I’m already in the middle of cooking a meal — who can afford to wait several days for a bottle of soy sauce?”

Rural consumers, especially farmers, also place greater emphasis on interactivity and the sensory experience of buying things in-person than their urban counterparts. They are used to appraising the texture of fabrics with their hands, observing the freshness of ingredients up-close, and taste-testing consumer goods such as tobacco, alcohol, tea, and sugar. And they enjoy the ability to haggle with sellers and buy on credit. In the words of one: “Whose family hasn’t fallen on hard times before? They (Taole) lack humanity — they won’t allow you to place even a single order on credit.”

Of course, that’s not to say all rural e-commerce efforts are doomed to fail. Over the past half-decade, China’s rural e-commerce push has produced a wide range of results: Some projects have successfully boosted the local economy and contributed to poverty alleviation; others have been launched to a chilly reception.

What sets the successful projects apart is how well they integrate their business into local communities. Doing so requires e-commerce firms to move in two directions simultaneously: selling industrial products into villages, and moving agricultural produce outward into cities. In practice, many rural e-commerce platforms focus on the former to win over the rural consumer market, while ignoring the importance of the latter. This only makes farmers feel inferior, as though they have nothing of value to sell, and further deepens the divide between urban and rural markets.

E-commerce has real potential to break down barriers between urban and rural markets. However, as the example of Gumu County shows us, ignoring the traditions of rural economies and consumption culture while attempting to transplant a fixed business model from the city to the countryside is not a recipe for success.

Translator: Lewis Wright; editors: Cai Yineng and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Zhang Zeqin.

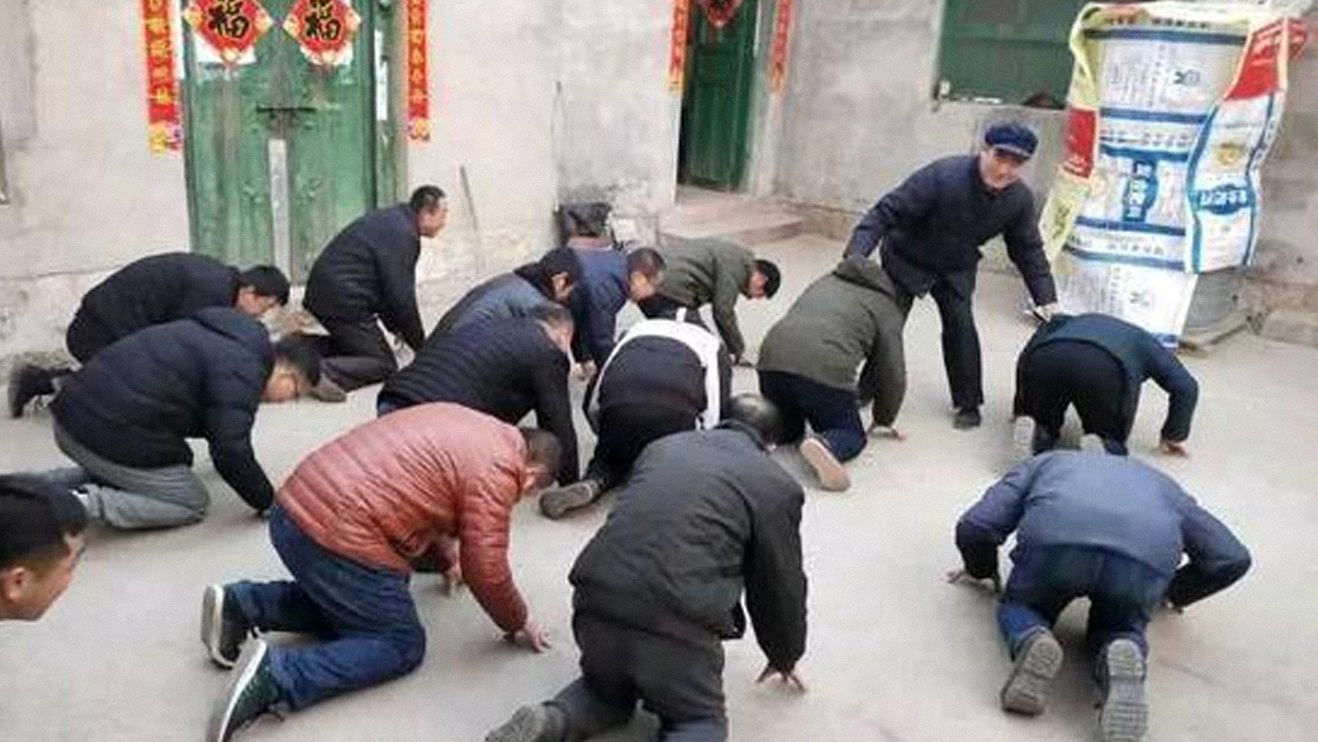

(Header image: Villagers take a break outside an e-commerce store, 2016. Courtesy of Zhang Wenxiao)