Beijing Divorce Court Values Wife’s 5 Years of Housework at $7,700

In a legal first under China’s new civil code, a Beijing court has ordered a man to pay his divorce-seeking wife thousands of dollars in compensation for shouldering five years’ worth of household chores, a case that has sparked heated discussion online.

According to China Women’s News, the official publication of the state-backed All-China Women’s Federation, the plaintiff, surnamed Wang, had filed for divorce from her husband, surnamed Chen, last year. She said her husband “didn’t care about or participate in any kind of chores around the house,” and would go to work each day, leaving her at home to care for their child. Beijing’s Fangshan District court ruled in her favor, ordering Chen to cough up 50,000 yuan ($7,700) for neglecting his share of the domestic duties.

“The division of a couple’s joint property after marriage typically entails divvying up tangible property. But housework may constitute intangible property value … not reflected among their physical assets,” the presiding judge, Feng Miao, told domestic media on Monday. The case is now awaiting appeal, though it’s unclear which side objected to the verdict.

Under China’s civil code, which came into effect in January, if one spouse bears more responsibility for raising children, caring for elderly relatives, assisting with chores, or performing other necessary but often thankless duties, they are entitled to seek compensation from their partner should they pursue divorce.

China’s marriage law, which the civil code replaced, stipulated that a divorce-seeking spouse could only request such compensation if both partners had signed a prenuptial agreement that included the relevant provisions — an uncommon practice among Chinese couples.

While some online have suggested the court’s verdict is a positive step toward recognizing the value of domestic duties within the family unit, others have said the proposed sum is insultingly low, given the often disproportionate burden borne by China’s housewives. According to a media outlet’s online poll, 93% of more than 400,000 respondents said the plaintiff deserved more than 50,000 yuan for her years of work.

“I feel that the job of a full-time housewife is underestimated. In Beijing, hiring a nanny costs way more than 50,000 yuan per year,” read the most popular comment under a related media post.

Still, Zhang Yan, the secretary-general of the Shenyang Lawyers Association’s marriage and family law committee, told Sixth Tone the new compensation law can better protect homemakers’ rights.

“The homemaker not only must undertake a lot of chores, but (without a job) also faces the problem of long-term disconnection from society,” she said. “In terms of the dynamics of the husband-wife relationship, the latter is typically in the more vulnerable position.”

But Zhang feels there may still be issues related to the implementation of the current law, which doesn’t specify how compensation should be calculated and doesn’t suggest how a spouse should provide evidence of the value of their domestic work — a problem Wang, the plaintiff in the Beijing case, said she hopes will be rectified in the future.

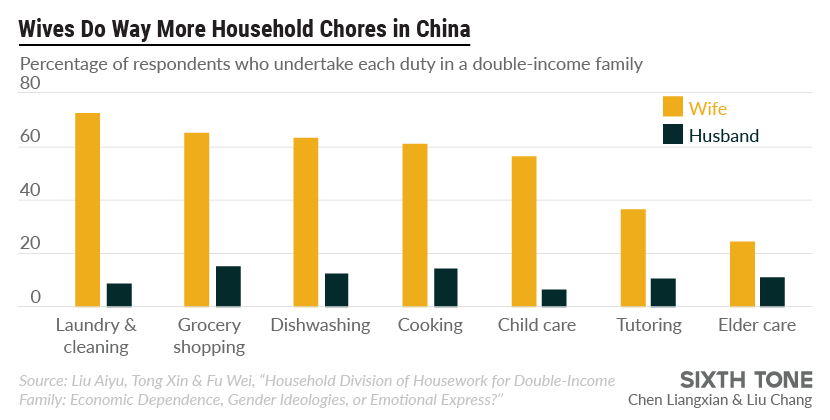

National trends make a strong case for why more attention should be paid to domestic work. According to data from the Geneva-based International Labour Organization, the rate of female employment in China is diminishing, from 63.9% in 2010 to 59.8% last year. Meanwhile, research from China’s National Bureau of Statistics suggests that in 2018, married women were doing three hours and 20 minutes of housework per day on average, an hour and a half more than their husbands.

In recent years, the housewife’s role has been a much-debated subject on Chinese social media, as well as in TV and film. Last year, Zhang Guimei, the well-known founder of China’s first free school for girls in the southwestern Yunnan province, raised eyebrows by saying she wouldn’t want to see her graduates become housewives, sparking discussion about whether they’re properly valued in Chinese society. Meanwhile, the so-called no kids, no ring lifestyle is becoming increasingly popular among young Chinese women who are reluctant to marry if it would mean stepping into a subordinate role.

Editor: David Paulk.

(Header image: Westend61/People Visual)