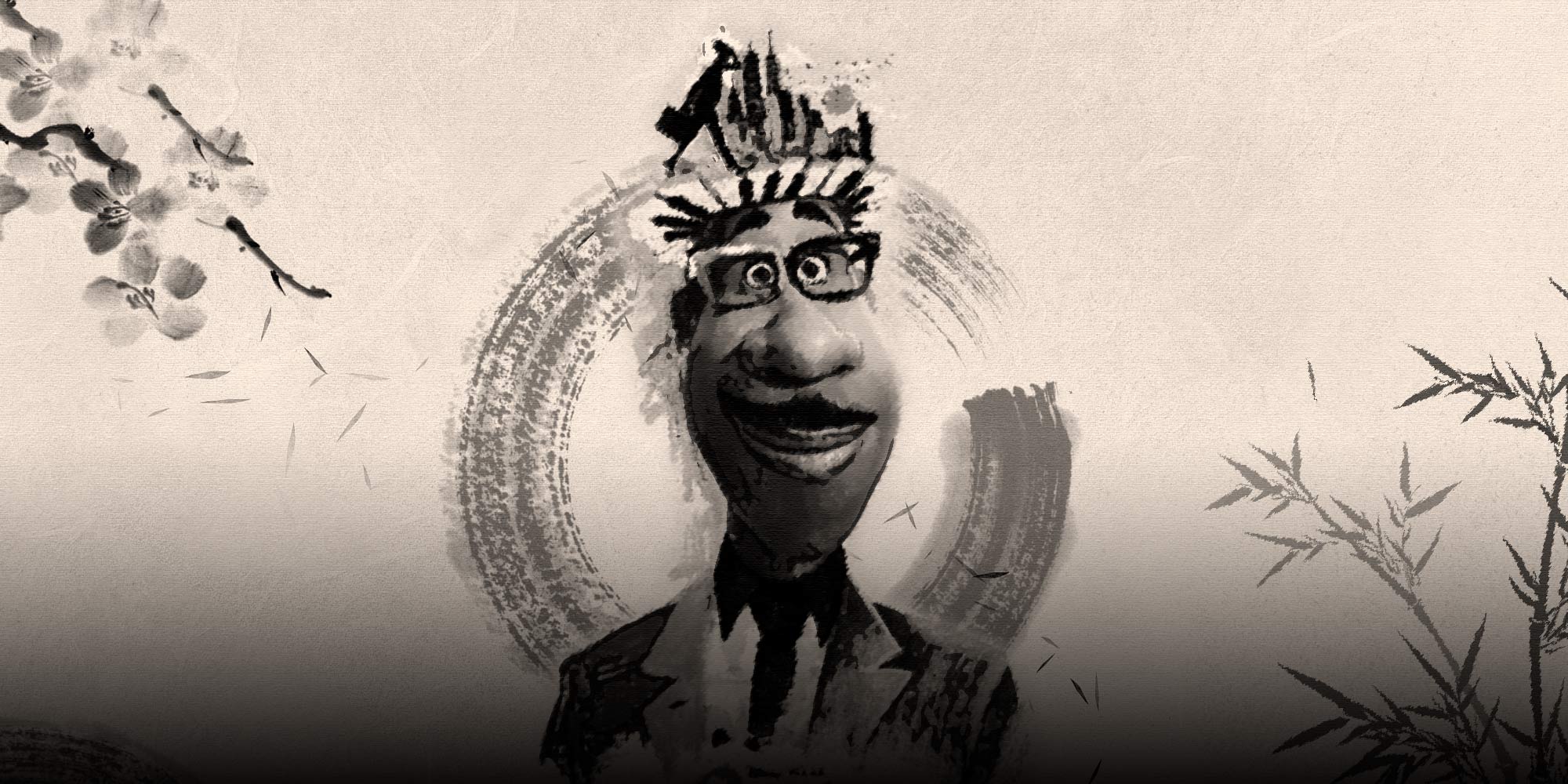

Is China Really Ready for Black Stories?

Since hitting Chinese theaters last December, the Oscar-nominated Disney-Pixar film “Soul” has pulled in more than 360 million yuan ($55.4 million) nationwide. Some people in the United States have cited this as evidence that the world — or at least China — is ready for movies featuring Black stories.

Well, maybe. It depends on the Black story.

“Soul” tells a touching story with deftness and care. Writer-director Pete Docter, together with cowriters Mike Jones and Kemp Powers, the latter of whom also co-directed, draw the viewer into an adventure of self- and world-discovery that almost anyone can relate to. In particular, the story and visuals portray life, not so much as we want it to be, but as we experience it. One user of the popular Chinese rating site Douban wrote that, “the crummy subway, the yellow taxi, the majestic Brooklyn … this is New York at its finest.” Another called the film “a dose of a healing cure for all the dagong ren out there,” using a word for “laborer” popular among overworked white-collar professionals. “Soul” uplifts at a time when pandemic-weary audiences in China and elsewhere want to see and feel swept up in a positive story.

Of course, another factor in the film’s favor is that Pixar films, in general, do well in China. Pixar’s previous release, “Coco,” raked in over 1.2 billion yuan in Chinese theaters with its story of family solidarity.

But “Soul” also benefitted from good word-of-mouth. The film bagged an opening-week score of 9.2 on the notoriously hard-to-please Douban, and while its score has since fallen slightly to a still-respectable 8.8, the movie gained momentum over time, from a so-so opening weekend of 36.17 million yuan to 90.18 million yuan its second weekend, and another 41.61 million yuan its third. To use a term from Hollywood’s past: The film had “legs.”

Given this success, does “Soul” represent a new opening in China for Black-themed or Black-led films? Again: It depends. Films featuring a Black protagonist still face headwinds in China. Colorism, which has roots in traditional Chinese class-based aesthetics as well as imported theories of scientific racism, is one source of resistance. Darkness means, in general, lower status. This plays out in all sorts of ways: from the stink eye Africans get to people’s choices on dating apps.

What may matter most, however, is that Chinese audiences see the Black cultural elements at the heart of a movie like “Soul” in ways totally distinct from how Black folk would see such content.

In sifting through the commentary on social media sites like Douban, streaming platform Bilibili, question-and-answer site Zhihu, and the box office aggregator Maoyan, those who praised “Soul” generally liked it for the following reasons: the design of the whimsical, Picasso-esque characters in the middle section of the movie; the classic Pixar-style attention to detail; the uplifting, warm-hearted music; and the overall sense of optimism. Very few reviews mentioned anything about Blackness. “Pixar” and “animation” were among the most commonly used tags on Douban, just as “Marvel” and “superhero” dominated the tags for 2018’s “Black Panther.” The message here is that, for Chinese viewers, these two films were first and foremost Pixar or Marvel films, and then genre films; the aspect of Blackness just didn’t ring any bells with Chinese audiences.

In 2015, when the #OscarsSoWhite campaign gained momentum in the U.S., Chinese audiences reacted coolly to the effort. Many netizens complained that the push for inclusion was too politically correct, a phrase that’s invoked frequently when Chinese netizens discuss movies with obviously “Black” features. This came to a head when “Black Panther” premiered. Chinese audiences lashed out at the film’s depiction of fictional kingdom Wakanda as a blend of high-tech utopia with traditional African elements like lip plates. The meaning and significance of these elements eluded them, registering merely as technicolor outfits or generic ceremonial dances.

Another theme emerges in the comments about prominent Black-themed films: a resistance to blending politics with art. In general, those making these comments understand the idea of political struggle and embracing a cause in the fight for true equality. But that fight belongs to Black people — others. It’s not the fight of Chinese people — us. Solidarity is one step too far.

It’s worth noting that audiences in China do not reject Black representation in films like “Green Book,” “The Pursuit of Happyness,” or “Soul.” These uplifting, warm-hearted stories appeal to a broad audience, with the box office results to show for it. However, once a film focuses on anti-Black oppression or anti-Black racism, it becomes imbued with a raw political tone that many Chinese audience members reject. The audience perceives the politics as getting in the way of the storytelling.

Mixing politics and storytelling makes sense for many filmmakers in the U.S., however. Rising racial tensions in American society since the 2016 U.S. presidential election have seen films like “Get Out” and “BlacKkKlansman” find wide audiences for their timely, relevant commentary on the sociocultural moment. These films have an entirely different tone and feel than “Green Book” and “The Pursuit of Happyness,” even though they, too, touch on the problems of racism.

Sidestepping politics in favor of focusing on the possibility for harmony and solidarity, compassion and empathy, helped “Soul” appeal to Chinese audiences. But its appeal was grounded in its “warm-heartedness,” rather than its Black themes. To be fair, the audience still gets exposed to Black culture, just not in a way they perceive as didactic. But like the other films featuring Black lead actors or key thematic material, a pattern emerges: Black-themed films can succeed in China — as long as their Blackness remains in the background.

This article was co-authored by Titus Levi, an associate professor at the USC-SJTU Institute of Cultural and Creative Industry.

Editors: Cai Yiwen and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Zhou Zhen.

(Header image: Visual elements from @皮克斯官方微博 on Weibo and Sino View/People Visual, re-edited by Ding Yining/Sixth Tone)