In Defense of the Cicada

The East Coast of the United States is currently witnessing the rise of Brood X, the region’s largest brood of periodical cicadas. After spending 17 years underground, trillions of cicada nymphs have surfaced from their burrows, shed their skins, and flown out across 15 states to mate, lay eggs, and die — all within a span of a few weeks.

This noisy arthropodal orgy has been referred to by various U.S. media outlets as “head-splitting” and an “infestation” — a veritable biblical plague. Whether by being a deafening nuisance during a stroll in the park or unwelcome crashers of outdoor wedding parties, swarms of screaming cicadas and the carcasses they leave behind are threatening to ruin people’s plans for what could be their first post-pandemic summer.

Their revulsion is understandable. Although the emergence of Brood X is a regular occurrence, cicadas do not feature significantly in America’s cultural imagination. As with most bugs, they are treated as irritable pests and nothing more.

For someone who grew up in southern China, however, cicadas are so ubiquitous that they are scarcely noticed. Their mating calls serve as background noise on summer days, and children climb trees to pick the vibrating critters for fun.

Apart from being a source of amusement, the cicada is one of the most familiar insects in Chinese culture and history. Jade carvings of cicadas have been found among artifacts from the Neolithic Liangzhu and Shijiahe cultures, which date back more than 4,000 years. Scholars revered the cicada’s ability to rhythmically reemerge into the world after spending years seemingly dormant underground. Their status was not so different from the mythical importance of scarabs in ancient Egypt, and the ancient Chinese ascribed supernatural powers like resurrection and regeneration to cicadas.

Because of this, cicadas played an important role in the funeral rituals of Chinese elites for thousands of years. The ancient Greeks placed coins in the mouths of their dead to help them pay the ferryman Charon to take them across the river to the underworld. The Chinese used jade cicadas instead, not to pay a toll, but because they believed that the cicadas would guide the dead through their process of rebirth back to the world of the living.

As Chinese philosophy developed, the cicada’s symbolism evolved from purely physical to moral. Various aspects of their life cycle were noted to be embodiments of gentlemanly virtue. Sima Qian, one of ancient China’s most eminent historians, used the cicada as a metaphor for the incorruptibility of the poet Qu Yuan: “Cicadas molt out of the filth, they float beyond the dust, and keep themselves from being stained by the world. They are truly beings who can wallow in mud and not be soiled.” Their diet, which consists solely of tree sap, was seen by the fourth-century historian Xu Guang as a sign that they do not partake in the sullied substances of the world: “The cicada takes from what is pure and virtuous, for they only drink dew and consume nothing else.”

But perhaps the greatest use of the cicada as a metaphor for ideal moral conduct comes from the fourth-century scholar Lu Yun: “The pattern on the cicada’s head signifies its erudition; its diet of air and dew signifies its purity; its refusal to consume crops signifies its incorruptibility; its lack of nests signifies its frugality; its punctual reappearance signifies its trustworthiness. Surely we must crown it and win its blessings!”

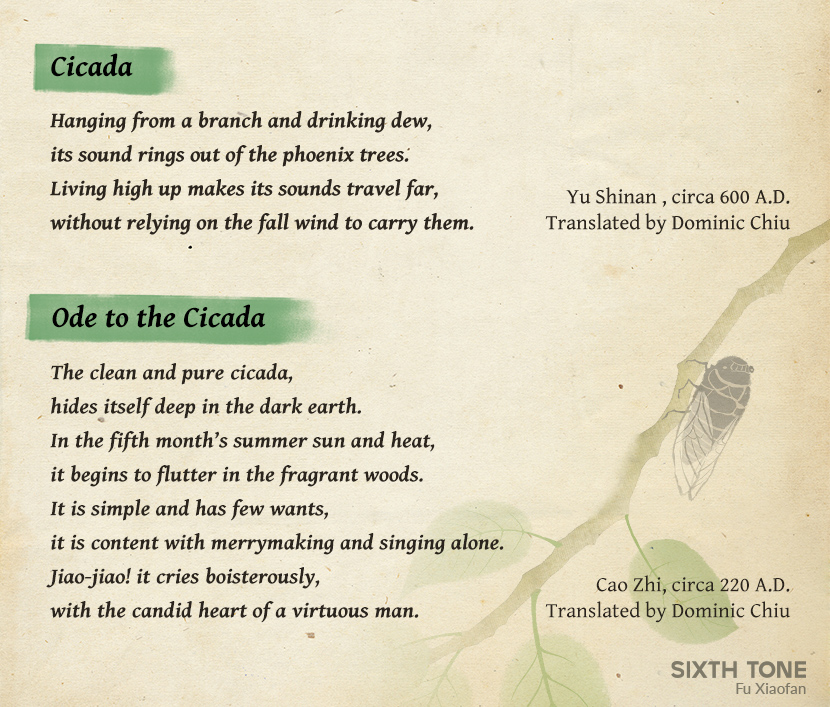

Poets like Cao Zhi and Yu Shinan also drew connections between cicadas and Confucian righteousness, but cicadas’ popularity wasn’t restricted to elite circles. They feature in popular idioms and proverbs like “(to escape) like a cicada shedding its golden shell” or “to be as silent as a cicada in winter.” And while not commonly eaten, cicadas are still seen as a delicacy by many in China today. Only, compared to the ornamental cicadas used as jade tokens in the mouths of the dead, the mouths of the living prefer their nymphs stir-fried. Cicada husks are even used in traditional Chinese medicine to treat a variety of conditions ranging from sore throat to tetanus.

More recently, the cicada has been the subject of public policy debates, with people either calling to cull or preserve it. Because of how cicadas damage the trees they feed on, in 2018, authorities in the eastern city of Hangzhou called on the public to hunt and eat them to reduce their numbers. Last year, complaints about noisy summer cicadas in urban areas of the southwestern Sichuan province led the state-run Xinhua media to issue an impassioned defense of the insect. The article reminded readers of the cicada’s prominence in traditional Chinese culture and made several ecological arguments for its appreciation.

Unfamiliarity with cicadas may have bred contempt among some Americans for the Brood X surge, but while some modern Chinese have lost their mythical sense and reverence for the insect, it is never far away from China’s cultural imagination. Whether as a viaticum, aphorism, food, or medicine, the cicada has and will forever remain on the tip of China’s tongues.

Editors: Lu Hua and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Wang Zhenhao.