The Snake in China’s Literary Garden

This May, a new film adaptation of the Cantonese opera “The Legend of the White Snake” hit theaters across China. Timed to coincide with the country’s unofficial May 20 Valentine’s Day holiday, the film was a dud at the box office, but those who did see it seemed to like it: The adaptation enjoys an average ranking of 8.2 on the hard-to-please social media and review site Douban, making it the highest ranked domestically produced movie of 2021.

“White Snake” is not the only White Snake-themed film slated to arrive in cinemas this year. “White Snake: Origins,” the sequel of the 2019 hit, is scheduled to premiere later this month — part of the recent wave of animated films based on traditional Chinese myths.

The story of the White Snake has many variations, but the version known to most contemporary Chinese goes something like this: After thousands of years of Taoist training, a white snake spirit gains the ability to transform into a beautiful young woman. In her new body, Lady White Snake falls in love with the dashing scholar Xu Xian and the pair quickly marry. During the Dragon Boat Festival, the spirit is tricked into consuming realgar wine, revealing her true form to a terrified Xu, who promptly dies from fright.

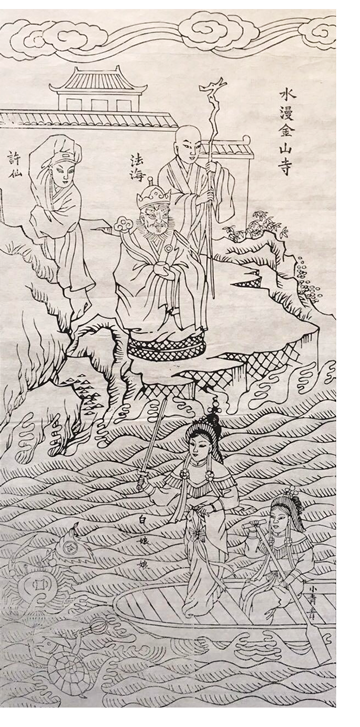

Distraught, Lady White Snake steals a magic herb that can bring the dead back to life and uses it to resurrect her husband. Believing that the union of humans and demons violates heavenly law, the monk Fahai forcibly separates the couple and takes a revived Xu Xian to Jinshan Temple. To rescue her husband, Lady White Snake floods the nearby mountains. Ultimately, however, the monk traps her in Leifeng Pagoda on the banks of West Lake in the eastern city of Hangzhou.

The evolution of the White Snake legend into something approximating a bittersweet story of star-crossed lovers is a recent development, but hardly unprecedented. The tale has always been adjusted to fit the morals and desires of contemporary audiences.

According to the early 20th century dramatist Tian Han, the seeds of the White Snake story were first sown in ancient India. Spreading west to Greece, they spawned the “Lamia and Lycius” legend. Moving the other direction, the story reached as far as Japan.

In China, a written version of the White Snake legend first appeared in the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD) collection of supernatural tales “Taiping Guangji,” or “Extensive Records of the Taiping Era.” In “Record of the White Snake,” Li Huang, a scholar from Longxi, meets a beautiful widow dressed all in white and accompanies her home for three days of bliss. Upon returning home, Li Huang feels weak and quickly sheds weight. A few days later, he dies suddenly, after which his body turns to pus, leaving only his head behind. Li’s family gets the address of the woman in white from his servant and travels there in search of answers, only to discover an abandoned garden known locally as the home of a large white snake.

For all its sensuality, the story was essentially a moral lesson: a warning to young men to beware of beautiful women of unknown origins and not to give in to their base desires.

A few centuries later, Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 AD) writer Feng Menglong added a few licks of black humor to the white snake story. In his version, titled “The White Maiden Locked for Eternity in the Leifeng Pagoda,” the snake spirit lures the poor clerk Xu Xuan (an early incarnation of the Xu Xian character) by claiming to be the newly widowed daughter of the local prefect. Unbothered by his background, she showers him with money and hires a matchmaker to propose marriage. When it turns out that the money she gave him was stolen from the county treasury, Xu Xuan is forced to flee to another city. To his great surprise, the White Maiden chases him and successfully persuades him to marry her. Her plans are foiled yet again when he goes out on the town wearing an extravagant outfit she had gifted him, only for a local wealthy man to recognize the clothes as his own.

Faced with two lawsuits, Xu Xuan feels remorseful and returns to his sister’s house. The White Maiden comes after him and viciously threatens him: If he doesn’t live with her, the streets of Hangzhou will run red with blood. With no salvation in sight, and ordinary Taoist priests powerless against her magic, Xu Xuan makes the decision to commit suicide by jumping into the lake. Just at this moment, the monk Fahai appears and collects the White Maiden in a bowl before locking her in the Leifeng Pagoda.

In Feng’s story, the white snake spirit is contemptuous of the laws and ethics of the mortal world. She stops at nothing to achieve her goals, killing without batting an eye and threatening to endanger an entire community. Xu, meanwhile, is bumbling, incompetent, and lustful. It is only when Fahai saves his life that he finally stops indulging in his physical desires. For all the added humorous flourishes, Feng’s tale echoes its Tang Dynasty forebear’s call to control one’s unnatural desires. Yet the message here is broader: In the highly commercialized, marketized, and urbanized Ming, Feng satirizes not only those who succumb to the temptations of the flesh, but also to material and societal advancement.

The legend would evolve further in the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911 AD). On one of the Emperor Qianlong’s inspection tours of the south, local gentry sought to impress him with a great theatrical production of the White Snake story. The scholar Fang Chengpei was recruited to synthesize all the old tales about the spirit into a new drama, “Leifeng Pagoda.” It was Fang who overturned traditional depictions of Lady White Snake as a conniving, evil spirit and instead explains in great detail how she was tricked into revealing her true form at the Dragon Boat Festival, risked death to steal the herb that could save her husband, rushed to Jinshan Temple to face off against Fahai, and how the couple reunited on a broken bridge before Lady White Snake was imprisoned.

Although Fang emphasized the purity of Lady White Snake’s love, he couldn't completely do away with the original story’s moral baggage. His Fahai was no villain — just a servant of the Buddha sent to terminate this “misbegotten relationship.” In fact, of all the story’s characters, only Xu Xuan is truly unlikeable. He comes across as cowardly, self-interested, and fickle — eager to enjoy the benefits of being married to a spirit, but unwilling to take responsibility the moment difficulties arise.

Of course, the male protagonist of a popular theatrical production cannot be an ungrateful oaf. From one production of Leifeng Pagoda to the next, Xu Xuan’s character evolved. Over time, writers changed his name to Xu Xian and softened his cold temperament. Fahai took Xu’s place as the show’s “villain,” a man so caught up with enforcing “heavenly law” — tianli — that he failed to see how unreasonable he was being.

This shift in characterization paralleled growing calls in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that people be allowed to marry who they wished, rather than whoever their parents selected. As the famed writer Lu Xun wrote in his 1924 essay “On the Fall of Leifeng Pagoda”: “Who doesn’t feel that Lady White Snake is hard done by, and who doesn’t blame Fahai for meddling in their affairs? The snake spirit is truly infatuated with Xu Xian, and Xu Xian marries her of his own accord — how is that anyone else’s business? He shows up to impose his unsolicited view of right and wrong.”

In the 1950s, Lady White Snake’s tale would be updated again, this time to meet the needs of a newly socialist China. Tian Han — who also composed the People’s Republic of China’s national anthem — saw Lady White Snake as a symbol of beauty, purity and free will, and worried that portraying Xu Xian as a cold and fickle-hearted man would convey a cynical message about love. Echoing the tropes of socialist realism, Tian’s script has Xu Xian momentarily faltering, before being touched by the sincerity and bravery of Lady White Snake. Her love acts as a catalyst for his character’s growth from fickle and selfish to steadfast and kind.

When a young monk at Jinshan Temple warns Xu that his wife is a demon, he replies: “But her heart is true.” Tian completed this millennia-old legend’s evolution from a misogynistic cautionary tale into a love story with a moving message: “Demons” with kind hearts are better than most people and, unless they are kindhearted, people are no better than demons. He also drastically rewrote the end of the story to bring it in line with the era’s revolutionary, anti-traditionalist leanings: The monk Fahai, who locks Lady White Snake in the Leifeng Pagoda, is portrayed as a heartless oppressor; Xu defeats him and destroys his pagoda..

May’s film adaptation largely follows Tian’s story, but with one crucial change: It reverts the ending to Feng’s more conservative version. Fahai is not evil; he merely seeks to defend the ethical order and uphold the notion that “everyone must respect their place in society.” In exchange for the safety of her husband and child, Lady White Snake voluntarily accepts her unjust punishment.

This narrative decision was startling to say the least. Half a century ago, Tian used the Lady White Snake myth to call oppressive power structures into question. Today’s storytellers seem more bent on re-embracing tradition than questioning it.

Translator: Lewis Wright; editors: Wu Haiyun and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Wang Zhenhao.

(Vertical image: A woodcut print showing Lady White Snake facing off against the monk Fahai at Jinshan Temple. From Kongfz.com)

(Header image: A promotional image for a recent adaptation of “The Legend of the White Snake.” From Douban)