Medicine and Meridians: A Chinese Artist’s View of Body and Spirit

Artists have been drawing inspiration from folklore and primitive beliefs to create murals, masks, and rituals throughout human history. Guo Fengyi, an artist from Shaanxi province, was one such artist who carried this time-honoured practice into the modern day. Although she never received formal training in fine arts, the talented artist produced hundreds of sprawling scroll paintings as an escape from her chronic illness and a way to express herself. Her work abounds with mystical elements drawn from Chinese mythology, ancient Taoist cosmology (such as the nine palaces and eight trigrams), and traditional medicinal diagrams.

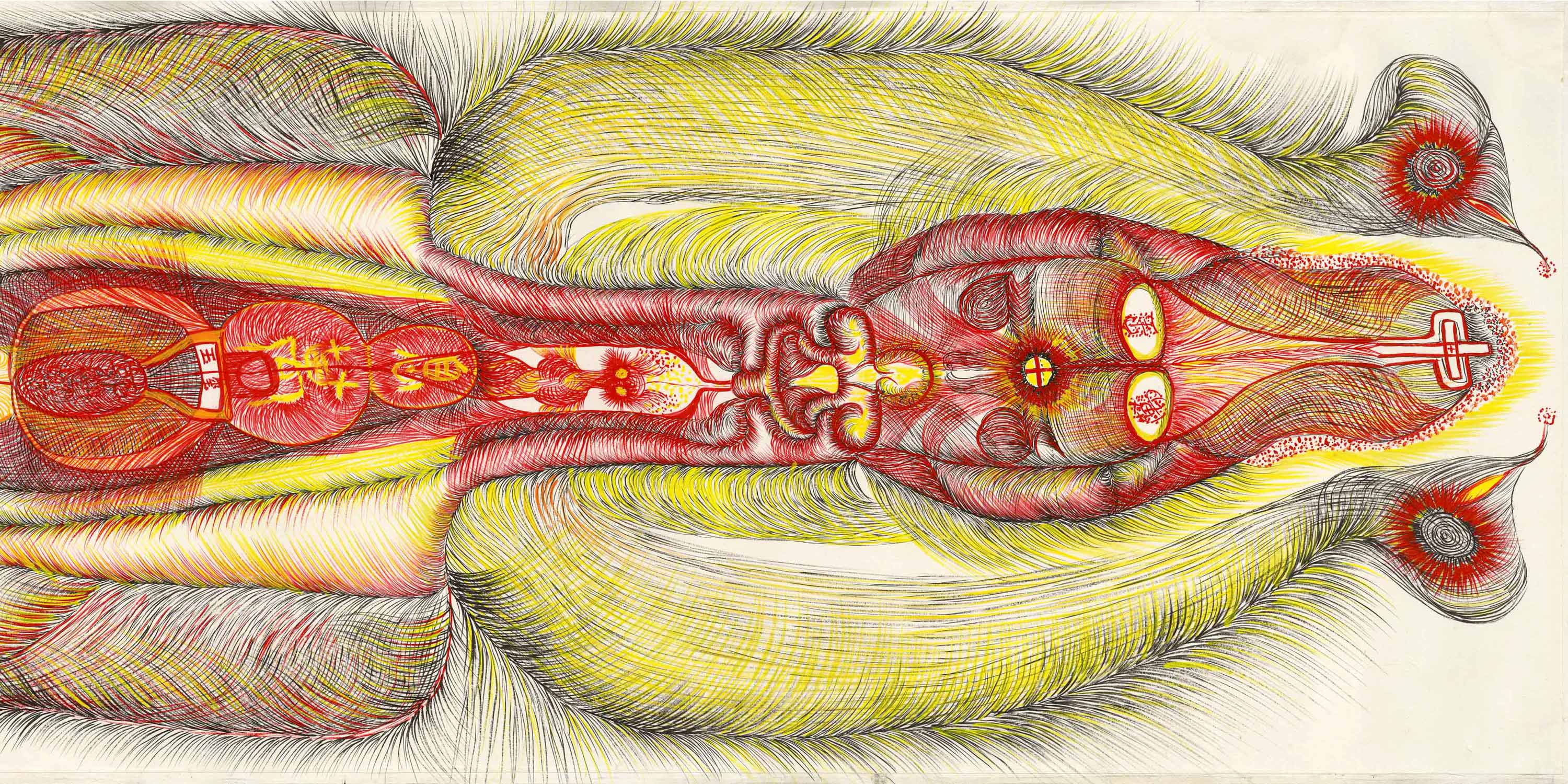

The artist’s works are now being showcased at an exhibition entitled “Cosmic Meridians” at Beijing’s Long March Space art gallery until March 26. The “Diagram of the Human Nervous System” series, with intricate line work that comes together to form peculiar-looking organisms, presents a down-to-earth conception of nature rooted in traditional culture. It comprises works named after natural elements, such as “Analytical Diagram of the Sun Seen from a Distance in the State of Qigong” and “Bagua Diagram of the Moon Seen from a Distance,” as well as works that mythologize real people, such as “Goddess Guo Fengyi” and “Suiren the Fire Maker.”

Guo’s work has left many intrigued since she passed away in 2010, as the mystery of her work will forever remain unresolved. Her humble background made her an outsider in the elitist contemporary art world. Guo was born in the city of Xi’an in 1942 and lost her father at the age of three. Though she aspired to study dramatic arts, harsh realities prevented her from pursuing her dream, leaving her with no choice but to take a menial job at a plastic factory. Due to the gruelling nature of her work, she developed severe arthritis and was forced to retire at the age of 39. As pain and prolonged insomnia weakened her body, she began to study traditional Chinese medicine, learning about the five agents from Yijing, or the “Book of Changes,” and the meridians of the human body while practicing qigong, a traditional Chinese medicine healing practice. These practices provided her with some comfort and relief.

Art curator Lucienne Peiry found that Guo began drawing in her journal as early as 1989. Her early works mostly consist of continuous, repetitive lines resembling heart rates, which together form vague silhouettes. In addition to her journal, Guo would also doodle on old calendars and her child’s exercise books, using just one or two felt tip marker pens. When she needed more than one page to extend the thin and dense lines, she would stick multiple sheets together to form a scroll so that she could keep on drawing.

By using everyday items such as calendars and notebooks, Guo demonstrated a strong desire to create. She once said: “I don’t feel any pressure to create art, and I don’t long for approval or compliments from anyone.”

In her 20 years of artistic creation, Guo produced thousands of drawings. Those showcased in the exhibition were created between 1989 and 2006. Her unique style creates the illusion that the characters in her drawings are constantly mutating and expanding, as if they could leap off the wall at any moment. After gaining recognition in the contemporary art world, Guo was invited to take part in the Long March project in 2002 and subsequently held her solo exhibitions there. She then began to use better quality materials, such as coloured inks and xuan paper, a type of rice paper. Her drawings feature irregular, continuous lines like body meridians that radiate outward from a fixed point. In these drawings, faces are usually vertically symmetrical and, like poker cards, can be looked at upside down. The theme of each piece — such as duality represented by traditional cultural symbols like the sun and the moon, or yin and yang — is often rendered explicitly in text that lies between the lines.

Much like her practice of qigong, Guo’s creative process was akin to a ritual. Her drawings depict visions inspired by these mythical practices. These drawings resemble labyrinths or historical artifacts, though the audience will never be able to find answers to the mysteries. One can only let their imagination run amok based on the fragments. By touching on mystical tradition, Guo’s highly distinctive artwork reminds us of the relationship between human and nature.

Translator: Lewis Wright; editors: Elise Mak and Ding Yining.

(Header image: “Level of Guo Fengyi’s Qigong Practice,” by Guo Fengyi, 1992. Courtesy of Long March Space)