Three Xie Jin Films to Watch

This year marks the 100th anniversary of Xie Jin’s birth. Arguably the first Chinese director to become a household name in China, the Zhejiang-born, Shanghai-raised Xie was responsible for some of the country’s best-loved films, from the upbeat paean to socialist sport, “Woman Basketball Player No. 5,” to “Hibiscus Town,” a searing depiction of the Cultural Revolution’s excesses.

Although early Chinese filmmakers produced a number of classic works in the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s, films only became widely accessible in China after the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949. Few directors were more successful in translating the abstract political concepts of the era into everyday terms than Xie. His wildly popular “woman trilogy” — 1957’s “Woman Basketball Player No. 5,” 1961’s “The Red Detachment of Women,” and 1964’s brilliant, controversial “Two Stage Sisters” — made him China’s most famous living director.

It also made him a target. “Two Stage Sisters” was criticized by the ascendant left-wing, and Xie spent most of the next 15 years in the political and professional wilderness. He wouldn’t fully recover until the 1980s, when he directed a series of “scar dramas” about the physical and psychological costs of the previous decades, including “The Legend of Tianyun Mountain,” “The Herdsman,” and perhaps his best-known work, “Hibiscus Town.”

In honor of Xie’s centennial year, the Shanghai International Film Festival — which Xie helped found — has organized a forum and career retrospective. For those not able to attend, here are three lesser-known films that highlight the qualities that made Xie a legend: his humor, his natural cadence, and his unusual eye for intimacy.

Big Li, Little Li, and Old Li (1962)

Xie’s only comedy — the director later referred to the genre as “difficult” to film in the 1960s — tells the story of Shanghai workers who must come together for a physical fitness. A rare film from the era to be shot in Shanghainese, Xie makes it accessible to a wider audience through the liberal use of silent film-style physical comedy. But its setting, a meat-processing plant overflowing with fresh pork, must have seemed impossibly luxurious to audiences only barely removed from the famine of the previous three years.

Watch it on 1905 (Chinese only).

Ah! Cradle (1979)

A personal favorite, the often overlooked “Ah! Cradle” was Xie’s last pre-“scar drama” film. Starring Zhu Xijuan, who played Wu Qionghua in Xie’s “The Red Detachment of Women,” it works as a spiritual successor to that film. Tired of being treated as a tool for reproduction, Zhu’s character strives to suppress her femininity after taking part in the revolution. But when she finds herself in the company of a gaggle of children, her maternal instinct unexpectedly resurfaces. The film’s underlying message — that the purpose of revolution isn’t revolution itself, but rather to give us the freedom to choose who we want to be — is characteristic of Xie, the warmest of China’s socialist-era directors.

Watch it on Bilibili (Chinese only).

The Herdsman (1982)

Adapted from Zhang Xianliang’s novel “Body and Soul,” “The Herdsman” is Xie’s most romantic film. On the surface, it tells the story of a man who has lived a life of hardship and the choice he faces between two families: one that can meet his material needs, the other his spiritual ones. In theory, it is a difficult choice, but Xie discards the tension to focus on the man’s catharsis as he realizes that his body and soul are one. For those who held to their principles over the previous three decades, the advent of “reform and opening-up” was cleansing — a fresh beginning, rather than a sad ending.

Huang Yong is a film critic who writes in Chinese under the pen name Sairen.

Translators: Lewis Wright and Kilian O’Donnell; editor: Wu Haiyun.

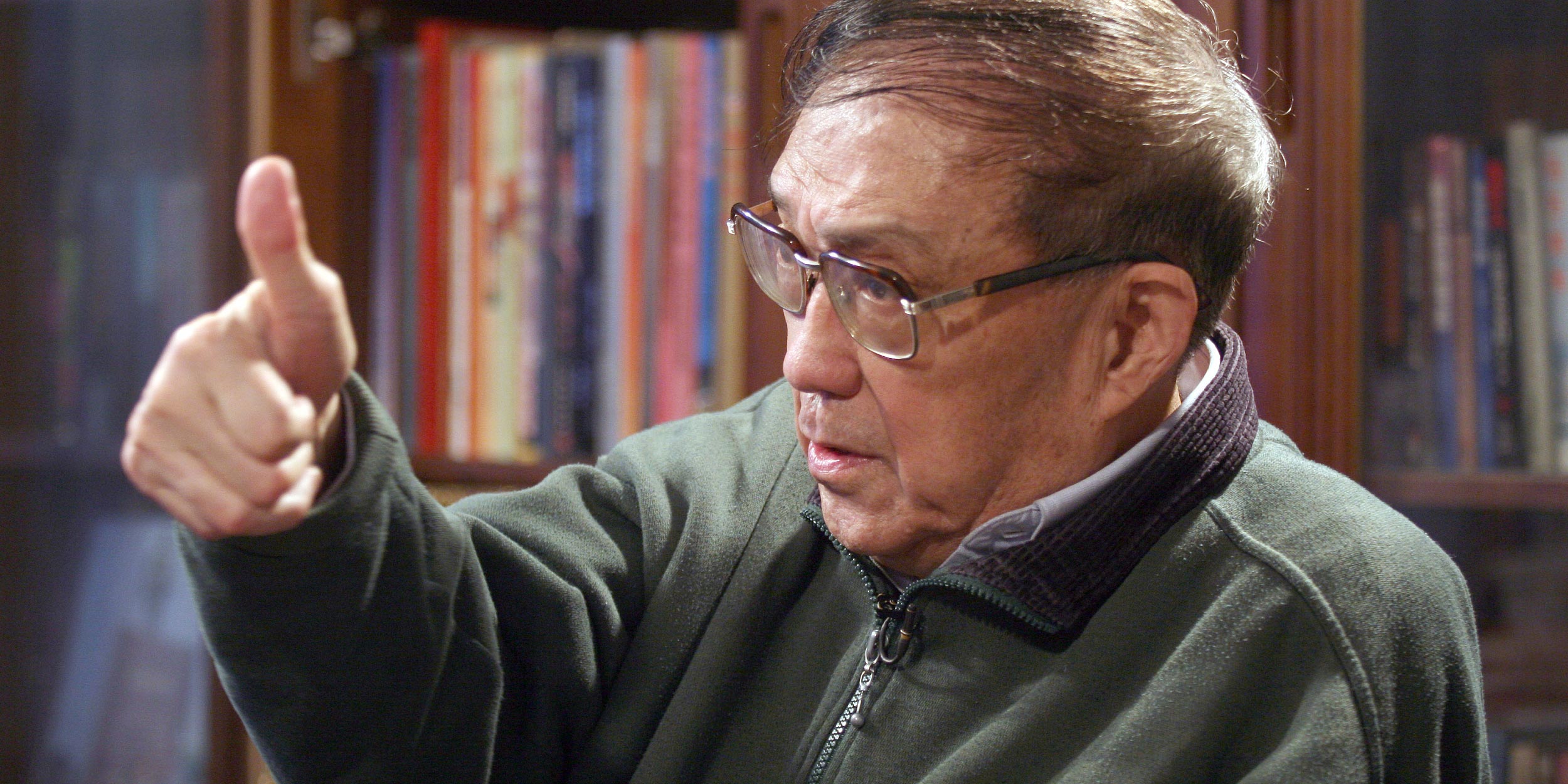

(Header image: Xie Jin in Shanghai, 2008. VCG)