Grad Students Treated Like Secretaries in Chinese Science Labs

As June comes to an end and summer vacation approaches, Ph.D. student Jessie, who would not give her real name because of possible repercussions in her professional life, reflects on her busy spring semester.

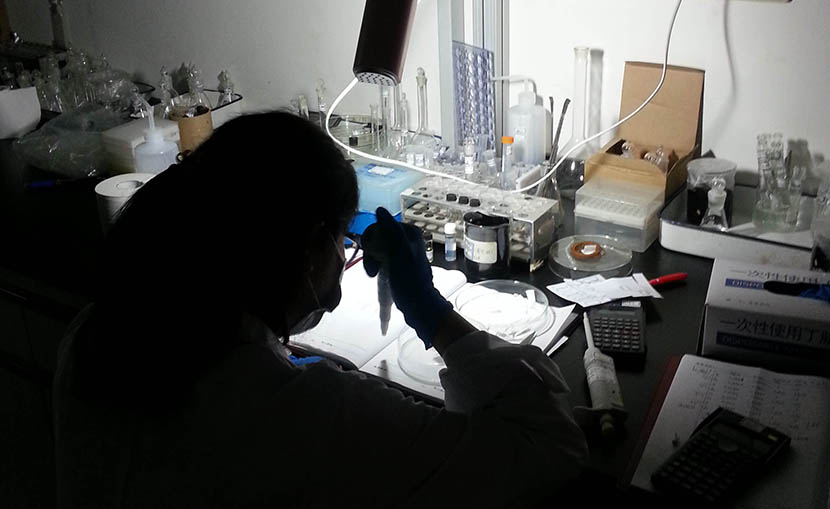

A 25-year-old grad student at China’s prestigious Peking University, Jessie hasn’t done any work on her research project for the past 20 weeks, but that hasn’t stopped her professor from keeping her occupied with other tasks.

Jessie spends her days doing administrative chores such as filing receipts for reimbursement, buying steamed buns with her student discount, making travel arrangements, editing PowerPoint presentations, fixing broken lab equipment, and purchasing bouquets of flowers on holidays. She does all of these things not for herself, but for her boss and his family.

“Whenever I see his office light on, I immediately feel depressed because it means he will give me more things to do,” Jessie tells Sixth Tone.

Peking University is one of the top two schools in China, yet Jessie doesn’t feel as though she’s working to her full potential in this elite environment — and she’s not alone.

In China science students working toward doctoral degrees are regularly called upon to perform mundane office tasks, from managing lab equipment to fetching mail for their supervisors. Universities rarely hire administrative support staff, so grad students are often expected to pick up the slack.

Students being used for cheap labor is a common phenomenon in Chinese higher education, according to Zhou Guangli, a professor at the Institute of Education Sciences at Beijing’s Renmin University. In 2010 Zhou surveyed 1,392 Ph.D. students, graduates, professors, and administrators for his book “Research on China’s Ph.D. Quality.”

But the issue of exploitation in China’s university laboratories came to a head earlier this year, when Li Peng died in a chemical explosion while working for his professor. According to Li’s sister, her brother’s supervisor, Zhang Jianyu, had forced the 25-year-old Master’s student to work in a wax factory that he owned. “I just need to hold on awhile longer; my bad luck is running out,” Li wrote in his notebook hours before the accident.

Li’s story is a prime example of how the relationship between student and supervisor can turn sour.

“It is certainly true that students in China have to do a lot of administrative work, and that some of them in fact act as secretaries,” says physicist Steffen Duhm of Soochow University. Duhm, who is originally from Germany, moved to China in 2012. He went on to point out that in contrast to Germany, Chinese professors are not provided with support staff.

China’s scientists are also under unique pressures that may affect their approaches to managing research teams. The central government’s focus on establishing dominance in the fields of science and innovation has led to an institutional obsession with getting published in reputable international journals.

“The university system in China is designed to value publishing in top-tier journals above all else, including the welfare of students,” says Kevin Huang, an American postdoctoral fellow in physics at Shanghai’s Fudan University.

Students like Jessie understand the pressure their professors face, but they have nevertheless become deeply disillusioned by the research environments at Chinese universities, to the extent that some of them are considering leaving academia altogether to pursue other careers.

For the past year, Jessie has met with her professor once a month. During these meetings, they discuss finances. Apart from these interactions, Jessie rarely sees him, though he is constantly in touch with her on messaging app QQ.

Having completed the bulk of her doctoral research, Jessie now spends most of her time writing grant applications, while her boss concentrates on networking: giving talks, attending conferences, meeting corporate representatives, and securing funds.

Jessie submitted her thesis in July of last year but is still waiting for feedback from her professor. “He’s only withholding my paper to maintain his control over me,” she says.

Renmin University’s Zhou says that there are currently no clear rules or regulations that stipulate or limit what supervisors can ask their students to do. “A key part of a supervisor’s role is to develop students’ talents, but what this entails exactly is a grey area,” he said.

When her professor asked her to manage his expenses last year, Jessie was hesitant. She refused the first time — citing her heavy workload as a teaching assistant — but felt unable to say no a second time. “My professor basically holds veto power over whether I graduate,” Jessie says. “Only when he looks at my paper and submits it can I graduate.”

In China, postgraduate requirements for students in the sciences are high. Science students at Peking University, for example, told Sixth Tone that they were required to publish at least one paper with a “high impact factor,” while Ph.D. students in science at Shanghai Jiao Tong University have to publish at least two high-quality papers, with at least one acceptance from a journal in the Thomson Reuters Science Citation Index, an authoritative listing of the world’s peer-reviewed scientific journals.

In almost all cases, professors have the final say in the submission process: If they refuse to sign off on a completed thesis, then the student cannot submit it for publication — and no publication means no graduation.

A third-year Master’s student surnamed Cheng, who is studying engineering at Tsinghua University, tells Sixth Tone that students who show more respect to their professors risk making themselves more vulnerable to exploitation. “I thought we were all equal, but I ended up organizing files for him on weekends,” she said.

Duhm suggests that the hierarchical nature of Chinese working culture might also contribute to detached relationships between students and professors. “Students generally do not question the requests of professors, and this lack of communication can lead to misunderstandings about research,” he tells Sixth Tone.

On Chinese social media, there is general discontent among postgraduate students regarding how they feel they are treated by professors. On Quora-like Q&A platform Zhihu, more than 300 users have posted angry anecdotes about their professors, with the most popular responses relating how students feel that their mentors are exploiting them and abusing an unbalanced academic system. “Thanks to my supervisor, I now know six ways of scamming funds,” one anonymous user wrote.

Fudan’s Huang points out that while the system might sound harsh to outsiders, professors tend to view their students as unskilled, cheap labor for good reason. “Lots of laboratory equipment is highly specialized, so it’s common to assign menial tasks to new students while they’re becoming more familiar with the laboratory,” he says. “That way they can learn from senior researchers and acquire necessary skills.”

Huang tells Sixth Tone that the time-consuming and difficult nature of lab work should also help students to better appreciate secretaries and lab technicians in the future. “Back in the U.S. I’ve met so many students who take the staff who support their scientific efforts for granted,” he says.

But to Jessie, the system has come to feel abusive and unfair: “If I had known getting a Ph.D. would be like this, why would I have come? I could have found a more satisfying job.”

“I came here with a dream of doing meaningful research,” she says. “But I think real breakthroughs in science can only occur in an environment where students have a genuine passion, where they are nurtured by their mentors, and where there is less pressure to find funding.”

(Header image: AMV Photo/VCG)