China Hopes CRISPR Can Beat Cancer

This month a team of doctors in China will become the first in the world to begin human testing of a controversial new gene-editing technology which could eventually be used to create so-called designer babies.

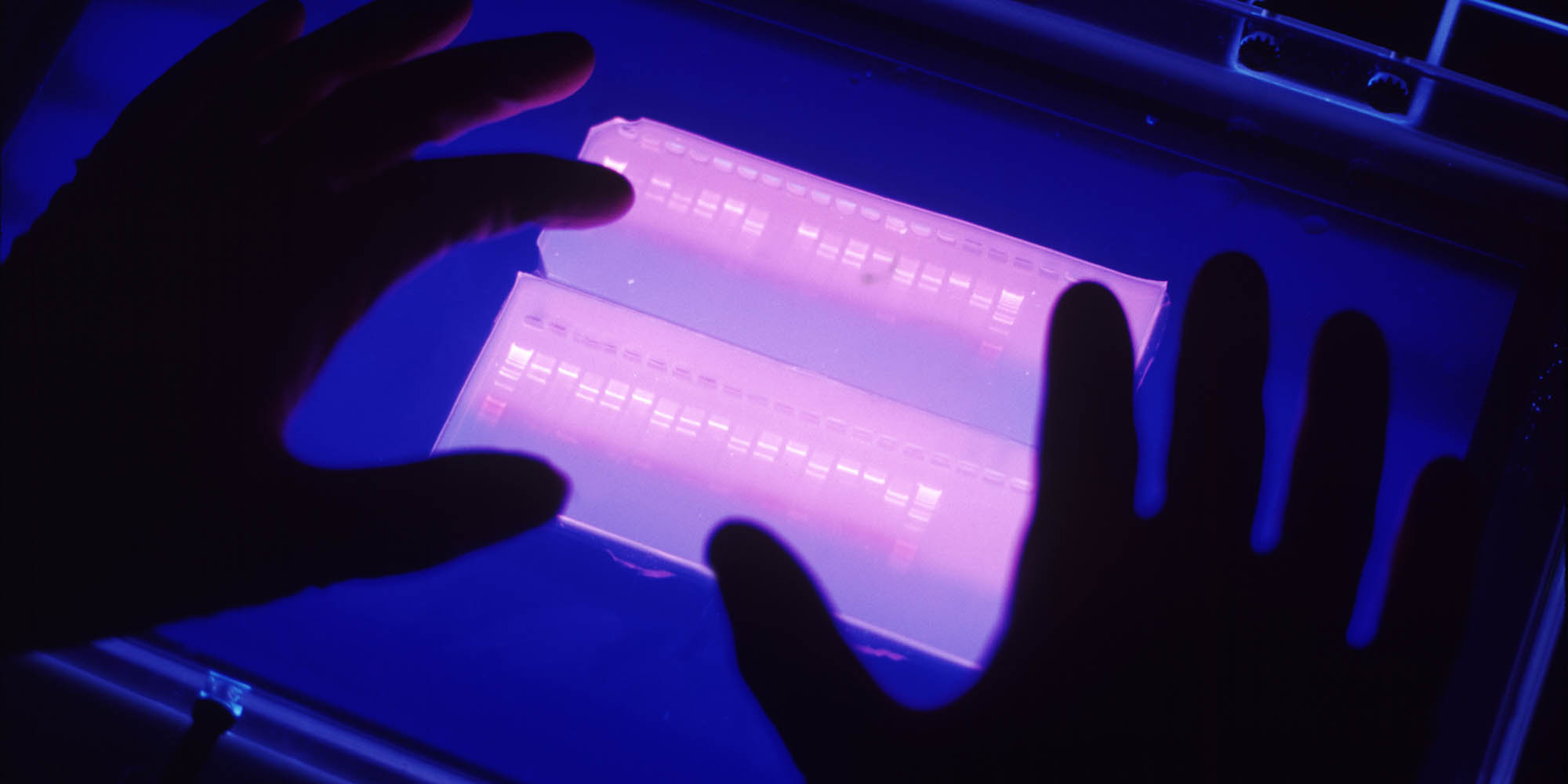

The new technology, called CRISPR-Cas9, will be used by scientists at Sichuan University’s West China Hospital to snip and replace specific sequences of DNA, according to a report in the scientific journal Nature. The scientists will add a new genetic sequence to the immune cells of patients with terminal lung cancer in an effort to create more powerful cells capable of effectively targeting and eradicating the cancer. If the trial is successful, CRISPR could soon be used to treat other diseases, and, in the future, even be used to modify the DNA sequences defining eye color or intelligence, paving the way for genetically engineered humans.

Although genetically modifying human genes is controversial, China has foisted itself to the forefront of the groundbreaking technology. In 2014, Chinese scientists became the first to use CRISPR in non-human primates when they engineered twin monkeys with two targeted cell mutations. Last year, researchers at Guangzhou’s Sun Yat-sen University used CRISPR to edit the genes of human embryos.

That China will now also pioneer CRISPR in humans is due not only to a different take on whether changing human DNA is ethical, but also to the country’s relatively quick and lax approval process for human trials, experts said. Qiu Renzong, chair of the Academic Committee at the Center for Bioethics at Peking Union Medical College, told Sixth Tone that the clinical trial for CRISPR only had to go through one approval stage.

“This project is in fact a regular trial, and not much different from a new drug trial,” he said, explaining that the only requirement for drugs to be tested on humans was an endorsement by the institutional review board (IRB) of a hospital.

Few hospital boards, however, have strict protocols for clinical trial applications. “Some IRBs are just stamps of approval, with no formal review,” Qiu said.

In other countries, similar trials have to be approved by several authorities, resulting in a lengthy process that includes IRBs, ethics committees, and national authorities.

In the U.S., for example, a similar trial was approved by the National Institutes of Health in June, but scientists who proposed the trial for 15 cancer patients won’t be able to start for several more months. Currently, they are still waiting for a green light from the Food and Drug Administration, as well as from the IRBs of the three centers where the research will take place.

Chang Liang, a Chinese researcher who works in the oncology department of MD Anderson Cancer Center, one of the three centers where the trial will be conducted, said that the U.S. approach ensures the decision won’t be made by a single review board. “The U.S. regulations are much tighter, and the FDA literally oversees everything,” Chang told Sixth Tone. “There are clear guidelines and protocols for development and approval of new therapies.”

Peking Union’s Qiu said that although he does not believe the trial to be ethically controversial, China needs to improve it’s review and approval process and bring it up to international standards.

“The review process for clinical trials — whether they meet scientific and ethical standards — should be enhanced,” Qiu said. He added that doctors’ evaluations of risks and benefits also need to improve, and that trials should be “conducted with patients’ consent and under transparent conditions.”

For all this to happen, though, Qiu believes the system must be reformed.

(Header image: Robert Essel NYC/Corbis/VCG)