Electric Road Tripping Hits Speed Bumps in China

On a recent afternoon in July, a young couple driving a white BYD Tang drove up to a charging station in eastern China’s Zhejiang province.

Their car’s battery needed recharging — a seemingly routine task that soon became a struggle. First they needed to figure out how the charger worked. Then they discovered that to use it, they needed a prepaid card issued by State Grid, the national utility provider. Thoroughly defeated, the couple walked to a nearby service station to grab a coffee instead.

Fortunately for them, the Tang is a hybrid, meaning they could continue their journey using the gasoline engine. Had it been a pure electric car, though, they wouldn’t have been so lucky.

For drivers of electric vehicles (EVs) in China, there is no single standardized app or payment system, which means car owners need to be able to shift between various payment methods when they take their electric cars on the road.

China aspires to become a haven for electric vehicles, as the government sees EVs as valuable on several fronts. First, they improve the country’s energy security by reducing dependence on imported oil. Second, policymakers hope their continued success will help China’s automotive industry to achieve a dominate position in what appears to be the future of global personal transportation. But a key to this success will be the need for EVs to capture the popular imagination of the Chinese consumer.

Last year 331,000 electric vehicles or new-energy vehicles — a term that includes both plug-in hybrids and pure electric vehicles — were sold in China. But in general, sales of pure EVs have been low, largely because consumers tend to feel more secure with plug-in hybrids that give them the option of using either electricity or gasoline. This choice increases the driver’s sense of security, especially over long distances.

The most commonly cited reason for not buying a fully electric car is “range anxiety” — the fear of not being able to find anywhere to charge and running out of power.

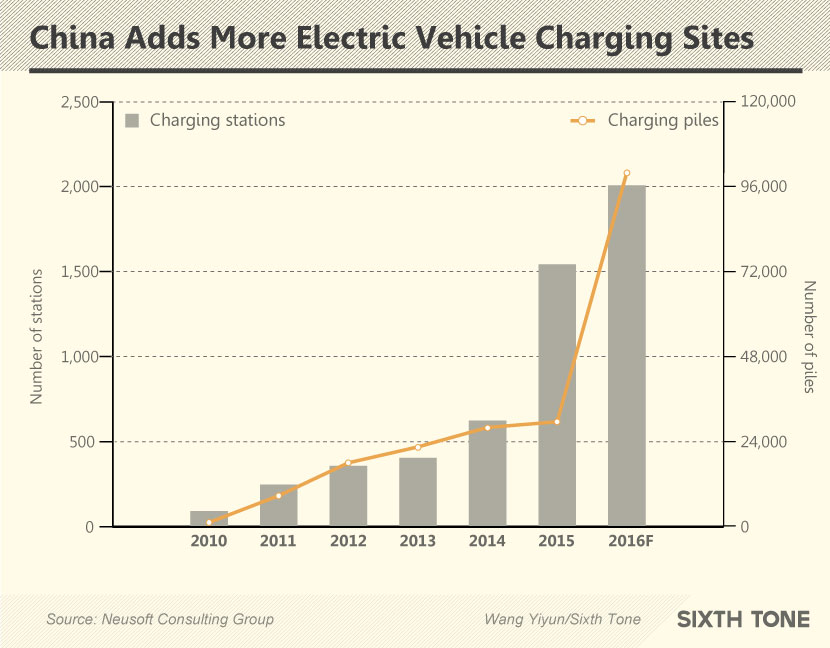

In early July, I set off with EV charging station expert David Zhang, a senior consultant at IT solutions company Neusoft, to test whether it was possible to drive from Shanghai to Hangzhou and back — a distance of about 400 kilometers — in an EV and, if so, to document the challenges we faced along the way. These two coastal cities also happen to be at the forefront of China’s push to electrify road transportation.

We used a Denza electric car provided by Deer EV, a rental company in Shanghai, for the test. Denza is a Shenzhen-based manufacturer jointly owned by Germany’s Daimler AG and Chinese battery and car manufacturer BYD.

Boasting a range of 300 kilometers, the Denza can travel farther than just about any electric car on the market not made by Tesla. Yet the model has failed to make even the slightest dent in the domestic market, selling just over 3,000 cars in China by the end of 2015. By comparison, more than 21 million passenger cars were sold in the country in the same year.

On this road trip, two aspects of China’s EV charging stations stood out. The first was the number of players elbowing their way in to corner charging-related payment systems. With the government handing out subsidies in exchange for building charging piles, a raft of companies have flooded the market, with each vendor using a different system. For example, State Grid uses a prepaid card, whereas Teld, the largest private operator, uses an app to control both the charging process and payment. All of this means that a typical electric-vehicle driver in China needs multiple apps, and often different prepaid cards, to find and operate charging stations provided by different vendors.

The other issue we encountered was finding charging points and, in some cases, the difficulties of using them once they were found.

On the outbound leg from Shanghai, we managed to reach Hangzhou with 42 kilometers to spare after a pit stop in Wuzhen, where we hooked the car up to a fast charger at an EV car-sharing station. When we tried to check the charging progress using an app, however, the pile abruptly cut off after charging 3 kW.

Like Tesla, Denza offers free charging at its own name-brand charging stations. On the morning of our return trip from Hangzhou to Shanghai, we hooked up the car to one of these stations at a shopping mall on the outskirts of the city. Charging in China can be a confusing process: There are two types of connectors, one fast and one slow, and the time required to charge depends on the power supply used. A full charge using the standard alternating current found in most electrical outlets takes about 15 hours, while a direct current charge can take less than five hours.

After we had waited nearly five hours, the battery charge read 89 percent. As we set off for Shanghai, the car projected a maximum range of 240 kilometers, but when we got on the highway, this range dropped to 200 kilometers. Before long, the range had fallen below the distance needed to get to Shanghai — meaning we would need another charge at some point along the way.

Most electric cars rely on regenerative braking to at least partially replenish their batteries. This means that when you take your foot off the accelerator, there is a noticeable reduction in speed, as if you were applying the brake. When this happens, the car is taking the kinetic energy of forward motion and converting it into electrical energy. But with highway driving, you are generally traveling at a near-constant speed, so there are fewer opportunities for the car to recharge itself via regenerative braking.

When we arrived at a service station later, the EV charging area was not in the main parking lot. Instead, we found a charging station in an area reserved for trucks. State Grid had installed four fast chargers, along with space for four more, under a covered area. But the area was cordoned off, and we had to move part of the barrier to plug in. We quickly charged around 5 kW of electricity and were on our way again. The full capacity of the Denza is 47.5 kilowatt-hours, which takes less than an hour using a fast charger.

At a service station called Jiaxing, we found a more accommodating setup for EV drivers. There was another covered area, another four State Grid chargers ready for use, and another four spots designated for future piles. But this time the station was sandwiched between two main parking lots. Although we still had enough power to get us back to Shanghai, David wanted to test a few more piles, so we charged the Denza for 5 yuan ($0.75).

Our last stop before reaching the city center of Shanghai was along the highway near the town of Fengjing. We followed signs to a service station, but when we arrived we found it was still under construction. With a shrug of the shoulders, we headed to the rental agency to return our EV. Its remaining range when we parked it for the last time read 70 kilometers.

Range anxiety continues to be a universal concern for EVs. However, in some European countries such as Norway and the U.K., where hybrids and electric vehicles have achieved a degree of popularity, people do not regularly go on journeys of over 200 kilometers. And while Chinese drivers are generally less likely than their American or Australian counterparts to embark on long journeys by car, there is a growing affinity among the Chinese for road trips. Until recently, most of the EVs sold in China had an advertised maximum range of 200 kilometers.

Despite the limited range of China-manufactured EVs, owners are finding that, with careful planning, they can be legitimate options for intercity travel. And as prices decrease and ranges increase, EVs will only continue to appeal to a wider spectrum of Chinese consumers.

(Header image: Charging stations line a parking garage at Beijing West Railway Station, Dec. 10, 2015. Hao Yi/VCG)