Anhui’s Migrant Workers Choose Spain Over Shenzhen

This is the second in a three-part series of articles about ethnic identity in China today. You can find articles one and three here.

Early on a rainy morning in September, 67-year-old Wang Guoyan sits on a bench inside a grocery store in Huaitang Village, smoking and chatting with his neighbors, and looking like he was born to be right here, doing exactly this.

Only two days earlier, he was in Ibiza, the small Spanish island in the Mediterranean where he lives nowadays. But for Wang, Huaitang will always be home, and he effortlessly slips back into the habits of the town: waking up before dawn and gossiping with his friends in the store right after breakfast. “People in Ibiza get up late,” Wang tells Sixth Tone. “Over there, I normally wake up around 10 a.m., but here in my hometown, I can easily readjust.”

On the surface, Huaitang Village in southern Anhui province seems like everywhere else in rural China: Old folks take care of their young grandchildren, and much of the middle generation is missing, having migrated to bigger cities for more opportunities. But they’ve ventured a little further afield than most.

Huaitang has gained a moniker within surrounding Shexian County as China’s “Euro Village” because more than half of the 2,000 registered villagers are now living in Europe, according to the county’s Overseas Chinese Affairs Office. The office’s director, Xiang Yulan, says the vast majority of Huaitang people abroad continue to hold Chinese citizenship.

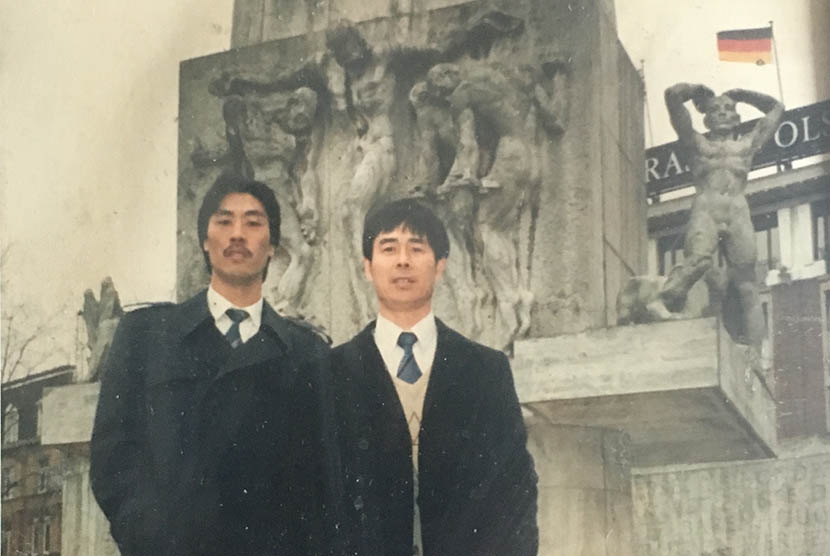

The first wave of Huaitang emigrants headed to Europe in the 1980s, and Wang was among them. The mid-1990s saw an even greater exodus of villagers, primarily to Spain, Italy, and France. But even after decades in Europe, many of them maintain extensive and regular contact with the village, sending their children there for school, or returning there after retirement.

For Wang, returning to Huaitang for holidays gives him a chance to reconnect with his old neighbors, play some mahjong, and voice his worries that his grandchildren — all born and raised in Ibiza — won’t know anything of their Chinese culture. He and his wife are determined to find ways to keep their descendants within the fold.

But Wang’s family is practiced at adapting to change, and at keeping their language and culture alive in a new environment. Like most of those who eventually made their way to Europe, Wang traces his ancestry back to Wenzhou, in Zhejiang province, a place known for bold and adventurous entrepreneurs.

A Hop and a Leap

Wenzhou natives have a reputation within China as a well-traveled bunch. The history of overseas migration from the city dates back more than 1,000 years to the Northern Song dynasty, when Wenzhou merchants sailed around the world with prized lacquerware and ceramics. By the mid-20th century, most Wenzhou people abroad were settled in Europe.

For those who remained, a major famine across Zhejiang province in the 1940s drove many to leave, and some traveled hundreds of kilometers to the fertile farmlands around Huaitang Village in Anhui province, where they could grow crops.

Now Anhui natives have become a minority in Huaitang, and the Wenzhou dialect — a branch of the Wu language tree, related to Shanghainese — is the dominant language in the village. Many of the families with Wenzhou origins are distant relatives, and a good portion of them have the surname “Wang.”

Wang Guoyan was born in Huaitang a few years after he and his wife’s parents settled down there, but their families had kept in touch with relatives who had stayed in Wenzhou. The inspiration to go to Europe came from his wife’s brothers, who had already set up catering businesses in the Netherlands.

Wang was 39 years old when he made the decision to go abroad in 1988. He had barely traveled outside the village before the long flight, but he said he channeled the fearlessness of his ancestors, and made his way abroad.

The early years were rough. The only languages Wang spoke were Mandarin and Wenzhou dialect, but it didn’t matter much, because like most of the other villagers, he only ever worked in Chinese restaurants run by Wenzhou relatives, washing dishes, preparing ingredients, and hoping to get promoted to cook.

Some of his co-workers from the village didn’t even read or write Chinese. Wang spent most of his Sundays off writing home to his wife, and penning letters for illiterate co-workers. Phone calls were reserved for major events. Wang’s wife, Zhan Mingying, recalls the ordeal required to make a phone call: “I had to cycle to the post office in the county, where one minute cost more than 30 yuan,” or around $4.50.

After three years in the Netherlands, where he worked without a legal permit, Wang moved to Spain in 1991 in the hope that he’d be able to benefit from a more liberal immigration policy. It took him until 1997 to secure a residency permit, which allowed him to return home after a nine-year separation from his family. Soon after, he brought over his wife and children. They built their own restaurant business, and later moved into running a store selling everyday goods and small appliances.

The Wenzhou Spirit

Like many of his peers in the village, 36-year-old Wang Zhen had only a middle school education. When he moved to the coastal city of Alicante in 2000, it was a hub where 80 percent of the Huaitang villagers in Spain congregated, mostly working in catering, but he was determined to break out of the mold.

After a year laboring in the kitchen of a Chinese restaurant, Wang volunteered to become a waiter so he would have more opportunity to converse with locals. At first he had to rely on body language, but gradually he picked up Spanish. He slowly built up his own restaurant business, and has recently begun to expand into hotels and the auto detailing industry.

Wang attributes his business acumen to his Wenzhou roots. He says he employs workers from many different Chinese provinces in his restaurants, although their attitudes and goals vary.

“After four or five years, those from Zhejiang province always leave to start up their own businesses,” Wang says, while those from China’s northern provinces tend to stay on as employees. “Most northern people just want to save a certain amount of money and then go home,” he tells Sixth Tone.

Wang’s success and ambition were no surprise to his mother, Wang Meixiang, who looks after his children in Anhui. “When he was 8 years old, he bought a box of popsicles for 0.01 yuan each and peddled them all throughout the villages for 0.02 yuan each,” she tells Sixth Tone. “He knew at a young age how to profit from a price difference.”

Keeping Culture Close

These days, Wang Guoyan’s family enjoys a comfortable life on the small island of Ibiza, where they are the only family from Huaitang among fewer than 1,000 Chinese immigrants, and a total population just over 130,000. In 2014, when he turned 65, Wang started to receive an old-age pension from the Spanish government – 600 euros a month — though he remains a Chinese citizen.

But though life in Europe has grown easier, Wang and his wife Zhan are anxious at the thought of their grandchildren assimilating completely and losing their Chinese identity.

“They can only speak a little Mandarin, and the way they speak and think are completely foreign,” Wang says. “I’m worried that if they marry foreigners, my family will completely lose not only the Chinese way of thinking, but also the Chinese appearance.”

Zhan adds that she and Wang try to educate their grandchildren about their origins and traditions. “We’re always trying to brainwash them,” she says, “but sometimes they show no interest at all.” She hopes that her grandchildren will at least find Chinese partners in the future, if they don’t marry people with Wenzhou ancestry.

For Wang Zhen, part of the second wave of Huaitang immigrants in Europe, the only way to guarantee that his children would acknowledge their culture was to send them back to China.

He made the decision after seeing that his cousin’s son had grown up barely able to communicate in Chinese, and with no emotional attachment to the country at all. “He considers himself Spanish,” he says. “It would be unacceptable to me if my children thought that way.”

Though Wang Zhen has lived in Alicante for 16 years, his children will complete their primary and middle school education in Anhui province. “I have to make sure that they speak standard Chinese and understand that they are Chinese,” he told Sixth Tone from his European-style villa in Huaitang.

Left Behind, Sent Home

Many other emigrant parents share Wang Zhen’s views, which is why a primary school remains open in Huaitang despite the aging population. Most of the students were sent back to live with their grandparents when they were only a few months’ old, and typically they join their parents in Europe after they turn 10.

The school’s old-fashioned two-story campus is a sharp contrast against the flashy new residences surrounding it. There are only two classes, one for kindergarten-aged children, and another mixed class for first- and second-grade students. Often there are no qualified teachers available, and older students have to move into the city to continue their studies.

Wang Guoyu, a local villager, told Sixth Tone that in June this year, he and his wife sent away their grandson to be reunited with his parents in Spain. The boy had lived with his grandparents for more than 10 years, and 64-year-old Wang Guoyu wept to think of him.

“Luckily we now have smartphones, so I can often see him,” he says. “I spent a lot of time figuring out how to use the app after my grandson left. We normally call around 8 p.m. Beijing time.”

The old couple’s life is quiet without the boy. Some days they visit neighbors who have grandchildren sent back from Europe. During the daytime, Huaitang is almost silent except for a few trucks carrying construction materials.

The villagers love to build and renovate their homes, whether in a European style or the local Anhui style. Many of the village’s residential buildings have manicured gardens and private swimming pools funded by villagers working overseas. But with so many young people living and working abroad, most of these gorgeous structures stand half-empty, guarded by the elders who remain.

Yet these days, the allure of Europe is fading as China develops. “The income gap between China and other countries is becoming smaller and smaller,” Wang Zhen says. He plans to return to Anhui province when he retires from his job in Spain.

As the only son, Wang Zhen feels responsible for his parents, who are more accustomed to life in China. He also appreciates Chinese family values, and the strong, close sense of interconnectedness and responsibility between generations. “People in Spain will split the bill with everyone, even their parents,” he says.

Like most of his peers, Wang Zhen still holds Chinese citizenship, although his children will have the freedom to choose Spanish or Chinese citizenship when they turn 18. “That will be their own decision,” he says.

As for himself, Wang is unequivocal in his identity. “Wherever I am, I always consider myself Chinese,” he says. “Blood can never be changed.”

(Header image: A senior resident sits alone in her home in Huaitang Village, Anhui province, March 23, 2014. Her whole family lives in Europe while she stays in their hometown with a caregiver hired by her children. Wu Fang/VCG)