Developers Draw Shanghai Residents Back to the Waterside

Shanghai used to be a city crisscrossed by waterways, and dozens of street names still pay homage to the canals and creeks that run through its urban sprawl. Lying in the swampy Yangtze River Delta, this former fishing village witnessed an industrial boom following the establishment of its treaty port after the Opium Wars.

Though the city’s name literally translates as “on the sea,” these days the Yangtze’s immense forces of sedimentation have pushed the coastline well out of town. In addition, large-scale land reclamation projects since the 1950s have made great tracts of marshland suitable for human habitation, though with negative side effects for ecology and flood protection.

Until the middle of the last century, the spatial and economic development of the Yangtze Delta was propelled by an efficient network of waterways and canal towns. In “Farmers of Forty Centuries,” his tremendous 1911 travelogue across China, the Korean Peninsula, and Japan, F.H. King describes how more than 3,000 kilometers of waterways provided an ingenious transport system that simultaneously supported soil fertility and irrigation. This in turn prevented soil erosion and increased crop yields, turning the delta region into a veritable rice bowl.

King also predicted that China would become a world superpower, as “tilling the earth is the bottom condition of civilization.” To improve the fertility of the land, a great deal of mud was dredged from the canals and creeks and spread across farmers’ fields. At the same time, night soil from the cities was transported to the fields by boat to be used as natural fertilizer. To a large extent, these techniques contributed to the self-sufficiency of the region and of China as a whole.

Later, under Mao’s leadership, the Chinese government adopted policies that imposed human engineering on the surrounding landscape. In Mao’s bid to conquer nature, many natural waterways were transformed into canals, while others were dammed or filled in completely.

The eastward shift in the world’s economic center of gravity at the end of the last century has made highways, railroads, and airports the new currency of Shanghai’s development — a process accelerated by mass migration to the city from rural areas. Many remaining waterways and canal towns have been subsumed by the city’s rapid urbanization, and this has severed the long and fruitful relationship between the city and the water systems sustaining it.

Until recently, living by the waterside in Chinese cities was rarely an attractive option. Industrial development made many of them dirty and smelly, while others became repositories of household waste. As a result, aside from the few remaining traditional canal towns, there are very few high-quality riverside housing developments in Shanghai.

Fortunately, the 2010 World Expo played a key role in redefining Shanghai’s relationship with its waterfronts. Since then, authorities have made an effort to clean up the banks of the Huangpu, the main tributary of the Yangtze running through the city. Shanghai’s ports, wharves, and shipyards are being outsourced to new locations across the delta region, well away from the downtown area.

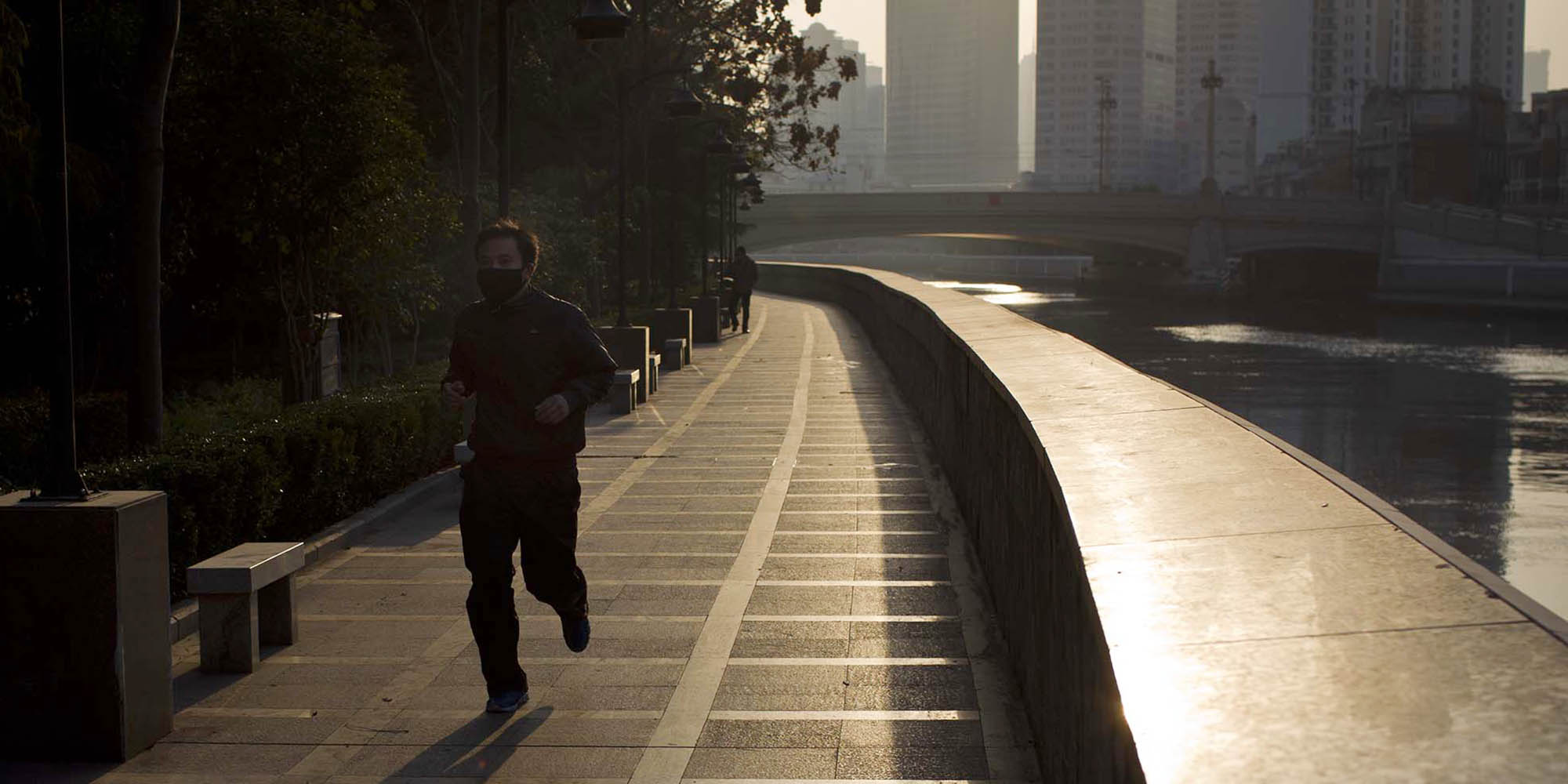

The redevelopment of Suzhou Creek, until recently one of the city’s most polluted water outlets, is indicative of a sea change in official attitudes. Luxurious new housing complexes have sprung up along its banks, overlooking the newly odor-free river. Meanwhile, ambitious projects seeking to rejuvenate the Huangpu’s riverbanks indicate that Shanghai is starting to embrace its position at the mouth of one of the country’s most iconic waterways. Planners have reimagined waterfronts as recreational spaces, with one initiative culminating in a recent design competition for 21-kilometer stretch of waterfront in Pudong, east of the river.

However, one still-unaddressed issue is the fact that most waterfront projects have so far taken the form of offices and high-end apartment buildings. While they sit in very attractive public spaces, they are the preserve of only a small proportion of citizens and are often relatively inaccessible, being far from metro and bus lines. The Cool Docks, a redeveloped area along the South Bund, is one example of an area where glitzy restaurants, hotels, and penthouses remain relatively unfilled by virtue of their remoteness from the beating heart of the city.

Additionally, the high water level means that, in many places, barriers prevent people from interacting directly with the water. While the dangers of swimming or fishing are clear, cities like London, New York, Rotterdam, and Hamburg have proved that a wide range of design solutions exist to bring people closer to the water safely, whether that be by introducing green slopes or providing riverbank walkways.

It is positive that Shanghai’s rivers are no longer an assault on the senses, but its new relationship with water still seems slightly platonic and superficial. However, with miles of canals still waiting to be developed, authorities will have many more opportunities to explore the city’s bond with its waterfront history. Hopefully, future projects will continue to see water as something to be protected, not neglected.

(Header image: A man runs along the bank of Suzhou Creek in Shanghai, Dec. 30, 2013. Kou Cong/Sixth Tone)