For Blind Students, Braille Exams Pave Way to Higher Education

Zheng Rongquan didn’t want to be a masseur or a musician. But in China, those who are born without eyesight have very limited career options and traditionally train in one of these two fields.

Zheng, however, was one of the first students who was able to take a different path. Last year, for the first time ever, blind students were offered the chance to take the gaokao — the national college entrance exam — in braille.

Having scored well on the test, Zheng, now 21, started studying education in 2015 at Wenzhou University in eastern China’s Zhejiang province. “This is what I want to do,” Zheng, now one year into his university studies, told Sixth Tone.

More than 9 million Chinese students sit the gaokao each year, but in the past, blind students were exempt because the test wasn’t available in braille. There are no exact figures on how many blind students are currently enrolled at schools across China. In the U.S., however, the American Printing House for the Blind reported 60,400 blind students at elementary and high schools in 2014. Given that China’s total population is four times that of the U.S., about 240,000 students could benefit from the braille gaokao.

For these students, the only option in the past was to take a special gaokao for the blind — a simplified version of the exam — which enabled them to enroll in special higher education programs that typically limited class offerings to music and massage therapy. The doors of China’s general universities remained closed to the blind, no matter how intelligent or gifted the students were.

“Since 2004, blind students have tried to apply to take part in the gaokao,” said Cai Cong, the head of YouRen, an online publication focusing on disability in China.

When China ratified the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2008, the national disability law was amended, and change seemed within reach. Blind people, the law stipulated, should be able to take any entrance test, whether it be a professional qualification examination or a service exam.

“China committed to offering a braille gaokao ... but it wasn’t easy to achieve,” said Zhong Jinghua, who serves on the administrative commission of the National Research Center for Sign Language and Braille. Major hurdles included concerns over leaked test documents and difficulties in finding suitable braille translators for the exam, Zhong said.

In 2014, rumors speculating that the law might finally take effect spread among China’s blind community. “I felt excited and nervous when I heard blind students might be able to take part in the gaokao,” said Lai Jiajun, who sat the grueling exam last year along with Zheng, answering the same questions as non-disabled students. “I’ve been preparing for this day since middle school,” Lai added.

Lai’s family moved from Hangzhou in Zhejiang province to Beijing in 2005 because the capital offered the best education for their blind son. They crammed two pianos into their 40-square-meter apartment — an investment in Lai’s future, his father said.

Lai originally planned to study the piano at one of the few universities in China that accepts blind students. But after he sat the braille gaokao, he was able to aim higher. He was granted admission to the Central Conservatory of Music, China’s most prestigious music school.

The school told Sixth Tone that he was the second blind student to ever study there. The first had been accepted into the conservatory’s middle school due to his exceptional musical talent and therefore did not have to take the gaokao to continue his studies at the university level.

In 2015, a total of eight students took the braille gaokao, according to government figures. The government did not release figures for 2016, but — citing state broadcaster CCTV — the China Disabled Persons’ Federation said that six people sat the exam this year.

Experts said they weren’t surprised that the number hadn’t increased. Although thousands of blind students could potentially take the braille gaokao, such students still face uncertain futures regardless of how well they score.

People with disabilities face significant obstacles throughout their lives, and are being discriminated against in the education system as well as in the workforce. A quota system gives companies tax breaks for hiring people with disabilities, but they are often not fulfilled. Generally, the income gap between employees with a disability and those without is growing, and, recently, people with disabilities have struggled even more to find jobs than in the past, the China Disabled Persons’ Federation found.

On top of that, many blind students seem ill-prepared to compete in the highly selective two-day exam. Several blind students interviewed for this story said that their blind classmates from special high schools decided to take to the traditional education path and sit the special, simplified gaokao for the blind. Most of them have spent the majority of their lives in the sheltered environments of schools specifically for blind students. If they risked taking the braille gaokao and failed, they’d have to wait a whole year to try again.

A look at Meng Jie School for the Blind in northern China’s Hebei province reveals why only a handful of students out of the potential thousands are taking the braille gaokao.

While other students in China might dream of becoming astronauts or politicians, most of the teenagers at the school were surprised to be asked about their career plans. Those who did respond said they wanted to be massage therapists – a common career for China’s blind.

When questioned further about why he wants to be a massage therapist, Hou Yaxuan, 13, said that it was the only career for blind students that offered a stable wage. “I want to survive on my own,” he said. When asked if he had thought about studying something more academic or considered other options, he fell silent.

At general universities that have not accepted blind students in the past, barriers to such students’ admission remain. Both blind students and experts in the field have asserted that administrators at many universities cannot fathom how blind students will fit in with their peers or even find their classrooms on campus.

Students like Zheng and Lai are now challenging these prejudices. Although their fight for equal educational opportunities is slow, they are making progress. Currently, Zheng is preparing for College English Test (CET). As for most other exams, he had to request special exam papers in braille from the Zhejiang education department.

“In addition to creating a new channel for blind students, the braille gaokao policy will lead a new trend and push more exams to open up to blind students and prepare braille papers for them,” YouRen’s Cai said.

Zheng feels that he has achieved a small victory simply by taking the general gaokao in braille and studying at the same university as non-disabled students. “Now my options are based on my grades,” he said, “not on my disability.”

With contributions from Li You and Denise Hruby.

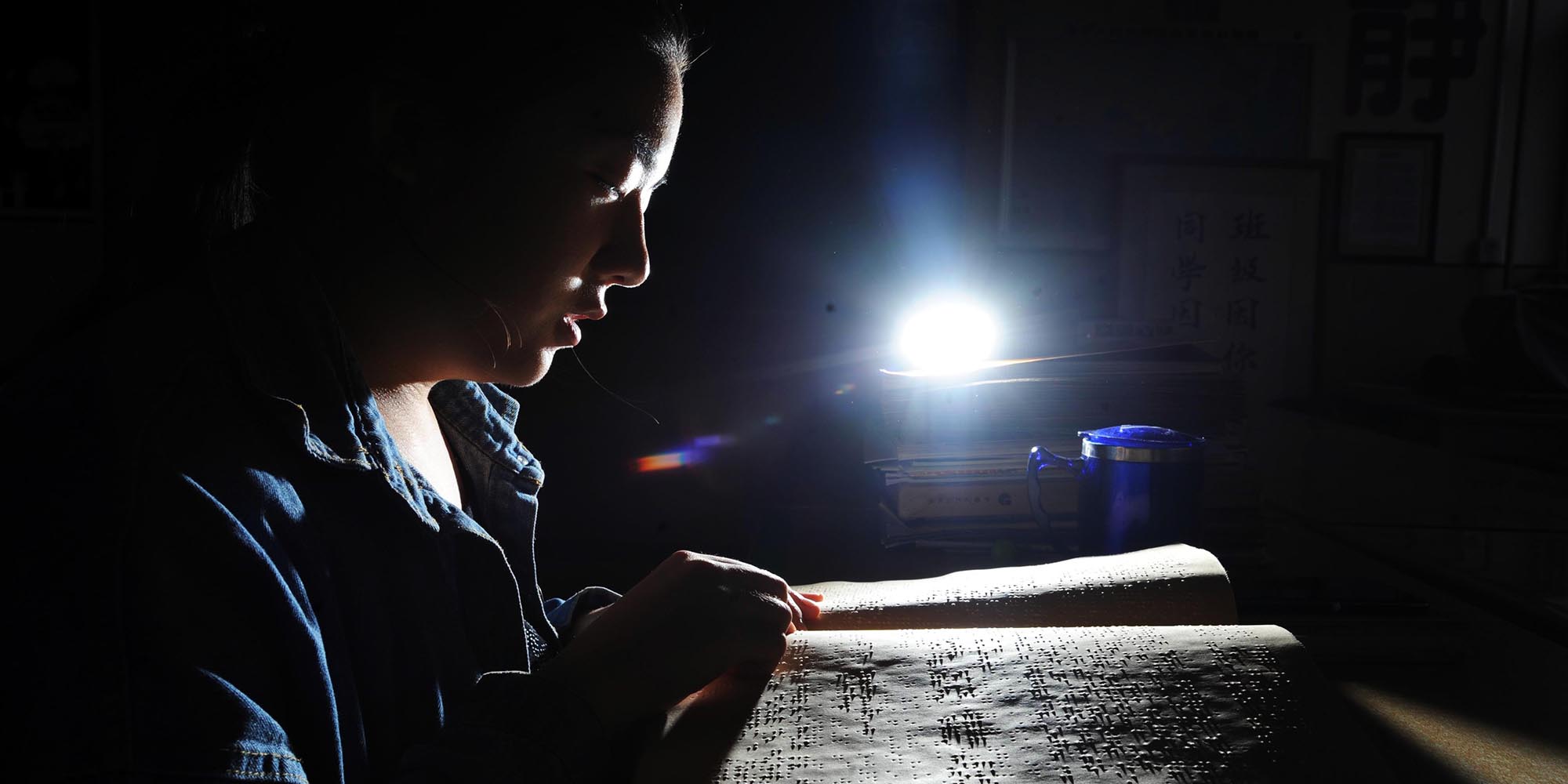

(Header image: A blind student reviews for the national college entrance exam, Qingdao, Shandong province, May 27, 2016. Mu Jiang/VCG)