How Weibo Reflects China’s National Pride and Shame

This is part three in a series about how Weibo affects our memories. You can find parts one and two here.

Over the past seven years, wildly popular Chinese microblogging site Weibo has shown the complex, ever-changing face of China to the world. Today, global media outlets scour Weibo in their research on China-related issues, while users themselves — aware of the site’s subjection to international scrutiny — modify what they post accordingly.

While Weibo posts cannot be boiled down to give a single overarching image of China, two key themes still emerge. First, Chinese Weibo users often display an acute sense of shame, which mainly stems from their previous failures to respond to news of global issues in acceptable ways. Second, netizens often take to Weibo in order to express national pride, especially when the Chinese government responds swiftly and reliably to humanitarian disasters in foreign lands.

In a previous article, I wrote about how Weibo users publish commemoration posts on the anniversaries of major disasters — posts that often take on highly ritualistic, conventionalized forms. A further aspect of this phenomenon sees users reflect on initial reactions to the event in question. Perhaps the best example of this comes from 2011, when Weibo users commemorated the 10-year anniversary of the Sept. 11 attacks on the World Trade Center in New York City.

For some, thinking back to 9/11 was an opportunity to express, in retrospect, the shame they felt for the callous reactions of fellow citizens at the time. On the day of the attacks, certain groups of Chinese netizens posted messages reveling in the perceived assault on American global power. Ten years later, many of the people who witnessed such heartlessness at the time logged on to publicly air their regrets.

One user described how, as a “brainwashed youth,” they had seen a group of classmates cheering the collapse of the Twin Towers. “That was a really important moment in my life,” they wrote, “because I then knew that I couldn’t let my [future] children become such coldhearted lapdogs.” This theme of personal growth was echoed by others advocating universal empathy, compassion for the suffering of fellow human beings, and a de-escalation of anti-foreign sentiment. One post went so far as to say that “narrow-minded nationalism is modern China’s greatest enemy.”

The following year, in the midst of the anti-Japanese protests that broke out in several Chinese cities following the escalation of the Diaoyu Islands territorial dispute, many Weibo users expressed national shame upon witnessing the protesters’ violent actions, which included destroying Japanese-branded cars and Japanese-owned businesses. This time, however, netizens focused more attention on China’s national image. In a post dated Sept. 15, 2012, one media columnist wrote: “In an era of advanced internet technology, these violent activities can reach worldwide audiences in just a few seconds, leading to international resentment of China which may actually put us in a disadvantaged position in the territorial dispute.”

Against the background of political crises, groups of Weibo users have co-opted the online platform to preach restraint and respect on the grounds of national image-building. For many, abandoning xenophobic attitudes toward foreigners and cooling the more explosive forms of Chinese nationalism are essential for China to stand proudly among the community of nations. At the same time, users also call for officials to value human life in ways propounded by liberal Western democracies. In the aftermath of the 2011 Wenzhou train collision, for example, users complained of the scant casualty information, describing the lack of news updates as “unimaginable” and praising the reputation for well-managed rescue operations in neighboring Japan.

More recently, however, Weibo users have taken to the web to celebrate China’s growing power, particularly on occasions where national resources are deployed to protect citizens traveling abroad. Following the April 2015 earthquake in Nepal, the search-and-rescue efforts undertaken by Chinese relief workers trended on Weibo for several days. During this time, some comments reflected warmly on having a reliable motherland, one that is “always by your side whenever you are in need.”

In November last year, a 7.8-magnitude earthquake struck Kaikoura, on the east coast of New Zealand. The consular assistance provided to Chinese tourists as they were evacuated from the local area created headline after headline on China’s social networks. These stories, in turn, became perfect illustrations for many Weibo users of how they could always rely on their country — and by association, their government — in times of crisis. One particular story, about a foreigner receiving help from Chinese authorities because his wife was a Chinese citizen, sparked a wave of patriotic posts.

The interaction of national shame and pride on Weibo reflects complicated perceptions of what Chinese citizens think their country ought to look like in the modern world. In order to become a civilized, respectable nation, many users demand that citizens reject blind patriotism, take a tolerant attitude toward other cultures, and look after each other in times of need. Memories of failing to live up to these ideals — on either an individual or collective level — inform the “shame posts” that drive online opinion further toward realizing those goals. Taken together, the chaotic mosaic of social media posts forms a rather incoherent, self-contradictory national image — one that is often painfully self-aware.

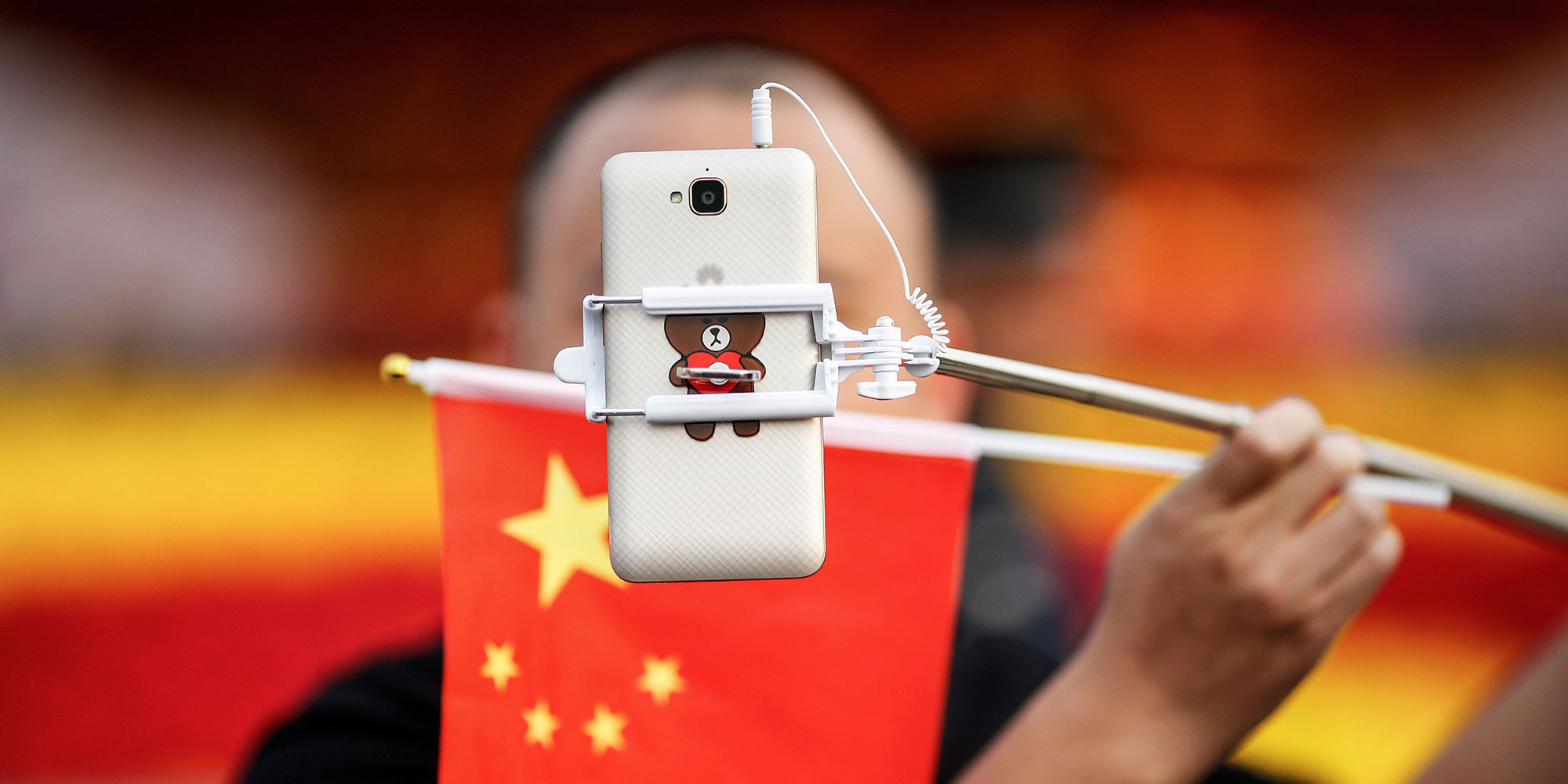

(Header image: A man holding a Chinese flag poses for a selfie in Tiananmen Square in celebration of the National Day holiday, Beijing, Oct. 1, 2016. Damir Sagolj/VCG)