Police Crack Down on ‘Hongbao’ Hackers

Given the sheer volume of funds transferred through WeChat on a daily basis, it’s perhaps not a surprise that the messaging app has become a prime target for scammers.

Police in the eastern Chinese province of Jiangsu recently uncovered a swindle centered on the increasingly popular virtual hongbao, or cash-filled red envelopes, according to local newspaper Modern Express on Thursday.

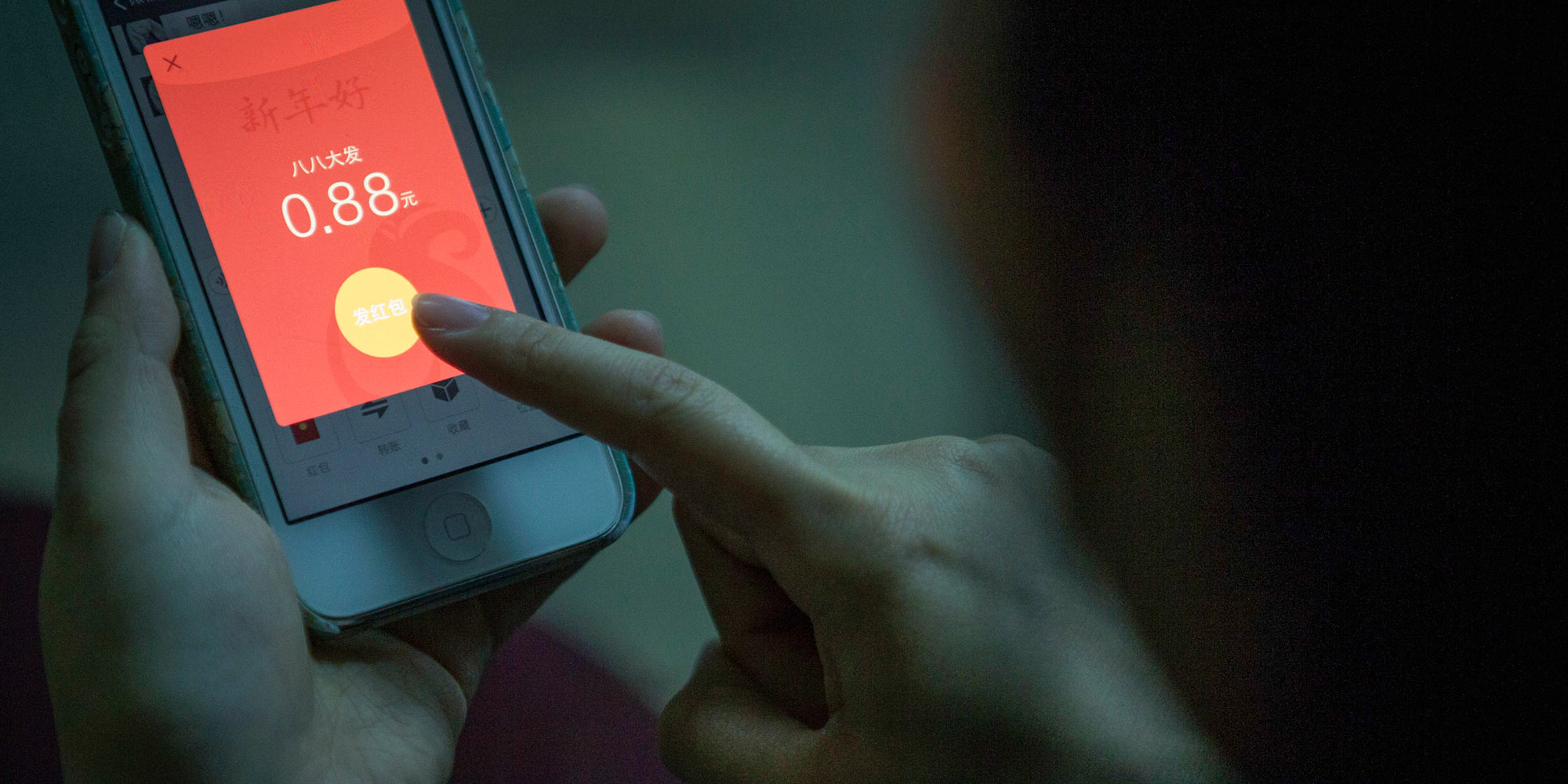

Gifting hongbao to family, friends, or co-workers has long been a common practice in China, especially around Chinese New Year. In 2014, Chinese internet giant Tencent took that practice online, allowing the now more than 800 million users of its WeChat app to send money electronically. Other players such as Alipay, Alibaba’s online payment platform, have since developed similar functionalities.

The 10 suspects rounded up by the authorities had allegedly written software that illegally listened in on data sent between users’ phones and WeChat’s servers. This way their app could detect when a user had received a hongbao and open it automatically.

On WeChat, giving away virtual red envelopes to a group of people turns into a money-grabbing game, with the other group members rushing to click on and “open” the red packet icon. When the money runs out, laggards and the inattentive are left empty-handed.

The scammers’ software apparently found its appeal to people, such as one victim surnamed Liu, who felt that he always missed out on tapping the hongbao in time to receive money.

After searching on the internet, Liu found an application called “King of the Hongbao-Grabbers” and paid the 800 yuan ($115) for a basic package that promised to put him among the quickest to snatch up the ephemeral prizes. Additional features, such as the ability to “see” inside the hongbao and determine the amount of money inside, cost Liu 1,000 yuan extra, he told Modern Express.

In total, the suspects had earned 30 million yuan from more than 600,000 customers.

Modern Express said that the scam had come to the attention of police following reports from people who installed these types of apps only to discover their phones started crashing frequently, leaving the buyers with the suspicion that they had been hacked.

Though the apps might work, they also present a security risk for users, as they could potentially steal personal information and even transfer money from users’ bank accounts, Modern Express said.

A spokesperson at Tencent’s security center told Sixth Tone in a written statement that the company issues warnings to people who use such apps, and in serious cases even closes their accounts completely.

Apps for the hongbao hungry are nevertheless widely available on Chinese internet sites, including Taobao, the country’s largest online marketplace, and they can be bought for as little as 36 yuan.

One seller from Taobao who offers such products told Sixth Tone that after installing the app and logging in, it would automatically discover hongbao and open them for the user.

The number of cases involving WeChat scams and frauds has been growing rapidly in recent years. According to Tencent’s list of the 10 most common scam tactics on WeChat, some nefarious individuals impersonate users after stealing their WeChat accounts and ask for money from their friends and relatives.

Others require users to scan QR codes that promise various products at low prices. In these cases, the QR codes can contain viruses that access the users’ personal information, including bank accounts and passwords.

Still others have been cheated by scammers who stick malicious QR codes on shared bicycles. When a would-be cyclist unlocks the bike by scanning the QR code with their phone, the money intended for the bike-sharing company is instead transferred to the scammers.

Despite a minefield of possible scams, WeChat’s virtual money features are wildly popular: One estimate says 46 billion virtual hongbao were given out during this year’s Spring Festival, up 43.4 percent from the previous year.

Editors: Colum Murphy and Kevin Schoenmakers.

(Header image: A mobile phone user opens an electronic red envelope on messaging app WeChat, Feb. 18, 2015. VCG)