Transgender Discrimination in Spotlight

On Monday in the southwestern Chinese province of Guizhou, a labor arbitration court heard China’s first case of unfair dismissal on the basis of transgender discrimination. Although the hearing was inconclusive — a result should arrive in late April — it has succeeded in bringing wider attention to the issue.

Mr. C, a 28-year-old transgender man, was fired from his job as a sales consultant at a health inspection company, Ciming Checkup, after only seven working days. He claims that, although his superior was satisfied with his work performance, he was told by a human resources manager that his attire reflected poorly on the company.

As a transgender man, Mr. C wears male clothing, but his identity documents are still marked female, as per his assignation at birth. He says that he’s pushing his case for the sake of recognition rather than compensation. Mr. C and his lawyer, Huang Sha, are asking for 600 yuan ($93) in unpaid wages, 2,000 yuan in compensation, and a formal written apology.

Though he was dismissed in April 2015, Mr. C wasn’t aware of his rights until he attended a seminar held by Wider Pro Bono Legal Center in Shenzhen. The center agreed to support his case and introduced him to Huang, an attorney who is part of a loose network of law professionals working on LGBT cases, known as the “Rainbow Lawyers.”

Mr. C filed the case on March 7 and the labor arbitration committee accepted the case on March 14. On March 30, the two parties underwent mediation in which Ciming agreed to pay wages but refused to apologize. According to Huang, in the hearing on Monday, the company confirmed that it expects female sales consultants to wear skirts and males to wear suits, but the company denied wrongdoing. Ciming Checkup declined to comment when approached by Sixth Tone.

A result is expected by April 28, as per the labor dispute mediation and arbitration law that has been in effect since May 2008.

Mr. C hopes that his case will bring awareness to the issues facing trans groups in China, as well as support the campaign for an independent national anti-discrimination law, which does not currently exist. China’s labor law contains an anti-discrimination clause which includes ethnicity, religion, and sex, but not sexual orientation or gender identity.

Liu Xiaonan, an associate professor at China University of Political Science and Law in Beijing, who has led the push for an independent anti-discrimination law, thinks the current laws are ineffective. “They just repeat very basic and generic statements that make it difficult for anyone to actually pursue a case,” she said to Sixth Tone. There is neither any specific detail nor a clear definition of what constitutes discrimination. Even when cases are successful, the compensation awarded is low — 2,000 yuan in a couple of recent sex discrimination cases. “That’s not enough to be a practical deterrent,” Liu said.

For Mr. C, his dismissal from Ciming was his first experience of workplace discrimination. He said his parents and peers are supportive and respectful of his gender identity. “My parents feel I’ve always been this way, so to them it only matters that I’m happy,” he told Sixth Tone.

Others say that trans discrimination is rife. Ms. Zhang, who is queer and transgender and works as an academic researcher in Beijing, told Sixth Tone that she has experienced discrimination often. “In every company,” she said, “there will be one or two people who show their disgust and make you feel like you can’t stay.”

Xu Bin, the head of sexual orientation and gender rights organization Tongyu, told Sixth Tone that some large companies in China have strong diversity policies and conduct human resources training on transphobia and homophobia. But so far it’s mostly private, foreign companies. She feels trans people experience even more discrimination than gay, lesbian, and bisexual non-transgender people because it’s more difficult for them to conceal their identity. “It’s very common for trans people to be mocked or bullied at work, sometimes to the point where people become afraid to go out in public at all,” she said.

But Xu said that the experience of trans people working in China also varies widely. “At first, most of the trans people who were in contact with NGOs were sex workers, because at that time HIV prevention was the main advocacy focus,” she said. Nowadays, she meets trans people in all fields, from Internet technology professionals and freelance graphic designers, to small business owners. It’s easier, of course, if you can be your own boss, or if you work in a more open-minded industry, Xu said. She pointed to Jin Xing, a contemporary dancer who has become the most famous and successful trans woman in China, now with her own primetime television show.

Sexism also complicates the attitudes that trans people encounter. Xu said that if they can endure being seen as women, female-to-male (FTM) trans people will face less harm or hatred than male-to-female (MTF) people, as Chinese culture is quite accepting of androgynous or masculine women. “In fact, there is a sort of stereotype that masculine women are very competent,” Xu said. But it is very difficult for FTM people to be recognized as men at work.

As well as workplace discrimination, trans people in China face issues with relation to healthcare and legal recognition. Though it’s possible for trans people in China to change their gender on identity documents, the application process is legally complex, and also requires the applicant to have undergone gender reassignment surgery.

Guidelines implemented in 2009 govern the approval process for trans people seeking gender reassignment surgeries such as mastectomy, chest contouring, hysterectomy, and genital surgeries. Each candidate for surgery must be over the age of 20, heterosexual, and with no criminal record. They must then apply to the police, tell their family about their plans for surgery, and obtain consent from their partner if married. The guidelines have been criticized by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) as “prohibitive, discriminatory, and incompatible” with international health standards.

An article in the medical journal, The Lancet, five Chinese surgeons estimate that there are 400,000 trans people in China, but fewer than 800 have undergone reassignment surgeries at approved hospitals in the last 30 years. Surgery is prohibitively expensive for many, and not desirable for all. Mr. C said of the genital surgery options available to trans men, “I think it’s a waste of money; the results aren’t that impressive.” He pointed to Taiwan, where since December 2013, trans people have been able to change their legal gender without undergoing any medical procedures.

Access to hormones is another issue. Mr. C said doctors refuse to prescribe hormones like testosterone and estrogen to trans people. The UNDP’s recently published Asia Pacific Trans Health Blueprint — a health reference document for trans communities in Asia — says that trans people in China often have to rely on purchasing hormones from unqualified manufacturers.

Legal recognition is spotty. For those who do manage to change the gender on their identity cards, the fact that the gender shown on school certificates and university degrees cannot be amended creates barriers to employment as they would be forcibly outed by presenting documents that don’t match. The UNDP has advocated for the government to allow such changes.

James Yang, a regional program analyst for the UNDP on sexual orientation and gender identity rights, told Sixth Tone the organization has been working with trans communities and governments across Asia to improve legal gender recognition. In the last decade, some of China’s neighboring countries have granted legal status to the MTF gender identities that have a long history in the region. However, FTM trans identity is less recognized.

Mr. C thinks that increased awareness and understanding of the trans community will help advance rights and recognition. But, he said, others disagree.

“I am standing up for our rights, but they ask, ‘Why are you making us visible? People will think you stand for all of us,’” Mr. C said. He admits that as one individual, there is a risk he will be seen to represent the whole diverse trans community. “There are trans people who are gay, who are bisexual, so if the public only sees me, they might think we’re all heterosexual,” he said.

There is also a belief among some that remaining hidden may prove safer than fighting for change. Mr. C said his critics are worried about being discovered. But he is hopeful that Chinese society is ready. “People may not accept those who are different to themselves, but I hope they can respect them.”

Additional reporting by Li You.

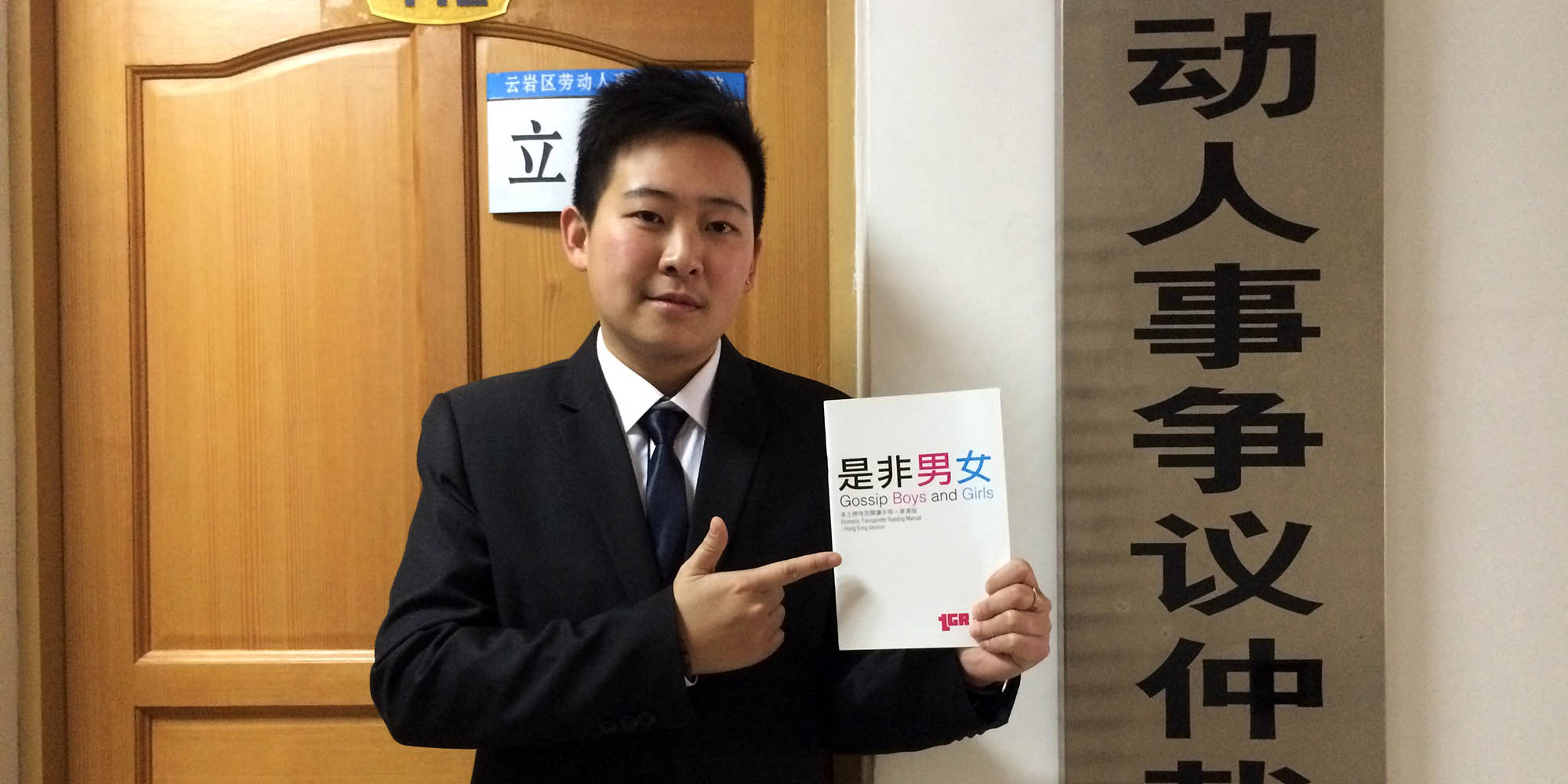

(Header image: Mr. C poses in front of the courtroom holding a copy of the ‘Domestic Transgender Reading Manual,’ in Guiyang, Guizhou province, April 11, 2016. Yang Xingbo, Li Jian/Guizhou City News for Sixth Tone)