China’s Video Streaming Sites Embrace ‘Bullet Screens’

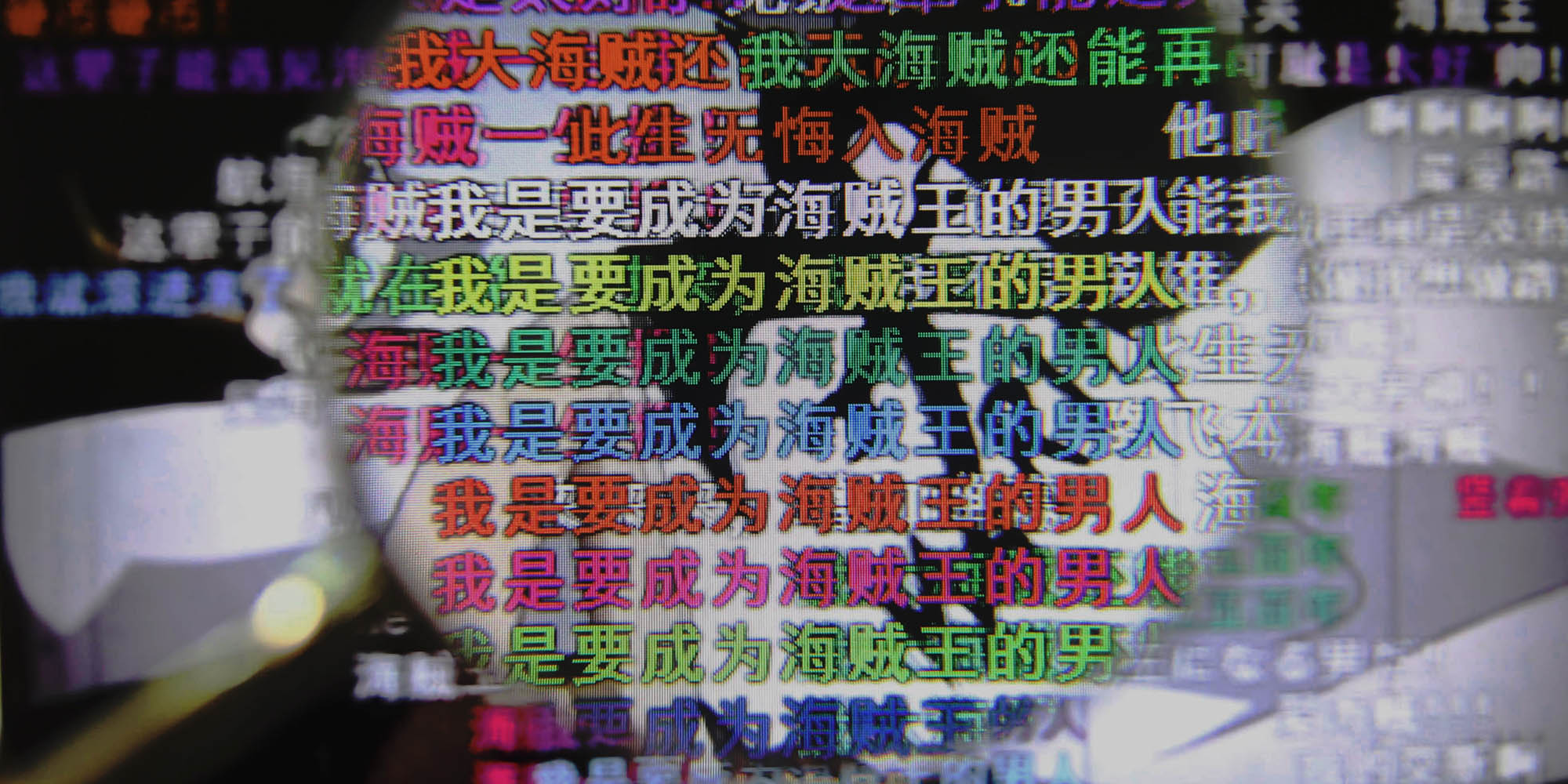

Watching a clip on Chinese video-streaming website Bilibili can be confusing — words in different colors suddenly appear out of nowhere and swoop across the screen, bombarding the viewer with jokes and snarky remarks about the video they are watching.

These messages are called danmu, which literally means “bullet screen” but can also be interpreted as a “barrage” — a more fitting translation seeing as the messages can become so numerous and intense that it becomes almost impossible to make out the underlying image.

Danmu are nevertheless wildly popular. Bilibili, just one of many Chinese video-streaming websites to offer the feature, has 50 million subscribers.

[node:field_quote]

The appeal of danmu lies in the directness of the messages. Though the function can — thankfully — be turned off, for those who opt in by default, the messages are unavoidable, and the draw to join in is hard to ignore. During live broadcasts, the messages function as a sort of massive chat room.

To Gao Hanning, a researcher of animation, comics, and gaming subcultures at Peking University, “Socializing is the most important function of danmu.” In an interview with Sixth Tone, she compared the experience to watching a sporting event in a bar with strangers.

The messages are fleeting — most fly across the screen once and then disappear — and show up anonymously, which is another characteristic that explains their popularity. Dong Qiqi, a 27-year-old curriculum designer in Guangzhou, in South China’s Guangdong province, told Sixth Tone that because of the anonymity, danmu carry few consequences, so people feel free to express themselves without having to worry about judgment or retribution.

So far, the danmu phenomenon has received little attention from China’s Internet censors. Still, Chinese video websites self-censor, and users are encouraged to report messages that are politically sensitive, hateful, or — worst of all — plot spoilers.

For regular video clips, danmu are just like any other comment function, but by being superimposed on top of videos, and by allowing users to choose exactly when and where their comments stream by, they are a source of creativity.

Danmu can be used to obscure the faces of unpopular TV show characters or used for “special effects,” such as a string of O’s resembling bubbles when a character falls into water. Another humorous use is several messages in green to temporarily give a character a “green hat” — in China, a symbol that a man’s wife is unfaithful.

Messages range from the insipid to the insightful. Users sometimes add danmu subtitles to foreign movies, and “researchers” chime in when understanding a video requires specialized knowledge, said “gentleman of the end of November,” a Bilibili user and a fan of danmu who wished to remain anonymous because her real name had previously been exposed on the Internet. In text messages, she cited the 1980s BBC political satire “Yes Minister,” which can be viewed on video-streaming website AcFun. In the episodes, users have added danmu comments with historical or legal background information whenever the show makes references too esoteric for most to understand.

Some of the more popular danmu messages require explanation themselves — such as “23333” for laughter, or “666666” for “awesome.” One danmu fan favorite — “High energy ahead! Non-combat personnel, please evacuate!” — is an homage to the phenomenon’s roots in the so-called animation, comics, and games (ACG) community, and, further back in history, Japan. The line is a quote from a Japanese animation classic, and it is used to warn viewers that an intense scene is coming up.

The first website to feature danmu comments was Japanese streaming website Niconico. The messages, known as danmaku in Japanese, started flying across screens as early as 2006. The function was first brought to China in 2008 by AcFun and has since won over millions of fans. Many other video-streaming websites have followed suit in recent years.

Danmu has also gained the attention of Chinese investors. In January of this year, AcFun raised $60 million from SoftBank China Capital following a previous round of $50 million last August from the Heyi Group and other companies. Heyi, which operates the popular Chinese video platforms Tudou and Youku, merged with the Alibaba Group in April. Media reports last November raised the possibility of Tencent, another of China’s Internet giants, buying a stake in Youku Tudou competitor Bilibili.

In a 2015 report, Beijing-based Internet consultancy group iResearch estimated the ACG community to have 219 million members in 2015. They are predominantly millennials, and their ranks are swelling.

“The majority of ACG enthusiasts are students or young workers,” said a former employee of AcFun, known to members of the community as “Chen Yin Nai Nai.” “Subject to the control of teachers, parents, and chaperones, they are hardly ever free, except when they are in the two-dimensional world,” she told Sixth Tone.

“Danmu bears more information than the video itself. And it engages users to participate,” said Mo Ran, CEO of AcFun, in an e-mail about why young people are drawn to danmu.

According to researcher Gao, the danmu phenomenon is so popular because of a need among the one-child generation — now mostly in their twenties — to socialize. Wang Xiaoyu, a psychological consultant who sometimes watches danmu with her 15-year-old daughter, concurred. “The kids are lonely and crave company,” she told Sixth Tone.

Gentleman of the end of November disagreed, but says people do seek connection through danmu. “I like sharing something enjoyable with a group of lovely people,” she said. “Laughter flying across the screen makes me happy.”

(Header image: Danmu comments cover the screen of Japanese animated series ‘One Piece.’ IC)