Traditional Chinese Opera Plots to Charm Politicians

After a landslide takes the lives of his wife and unborn baby, village party secretary Wang Xing stomachs his grief and devotes himself to the cause of relocating villagers to safer lands.

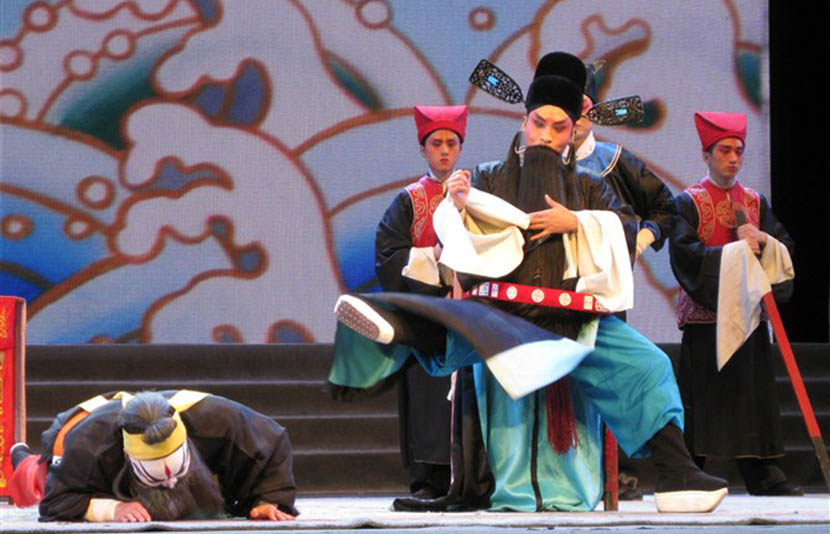

It sounds like a plot plucked from the dusty depths of communist mythology, but this is in fact the story of an opera set in the present day that premiered early last month. “Home,” a production by a small opera troupe based in the city of Weinan, in China’s northwestern Shaanxi province, tells the true story of an operation to relocate the habitants of Qiyan Village following a series of devastating storms.

“Home” is performed in the traditional operatic form qinqiang, a folk art form originating in Shaanxi province characterized by the sonorous wailing delivery of its vocal performers.

Competing with a booming movie industry and diversifying TV content, Chinese traditional operas face a crisis of dwindling audiences. While some operatic forms, like Peking opera originating in northern China and kunqu in the country’s south, still enjoy devoted, if small, audiences, many local traditional operas like qinqiang have been left fighting for survival.

In this situation, many local opera troupes have given up on the market, turning instead to the government for help. The strategy is simple: Create plots that follow the “main tune” — a euphemism for eulogizing the Communist Party, and, by extension, the government.

For the opera “Home,” the strategy seems to be working. Despite its humble proportions — the production team is made up of three small county-level opera troupes — its tale of the bravery of government officials has won the praise of China’s political establishment, in particular of Minister of Culture Luo Shugang. Luo’s admiration for “Home” has won it the honor of opening the 2016 China Art Festival set to be held in October.

To Chen Yongdong, an associate professor in opera studies at the Shanghai Theatre Academy, the reason many traditional opera troupes play up to the authorities is simply because they have nowhere to go. If a play is recognized by the government, he says, that means more performance opportunities, which in turn lead to more money.

To be successful, Chen tells Sixth Tone, an opera company must possess a lot of things, including market awareness, a promotional strategy, an understanding of audience demands, and of course quality in its performance. “Not a single one of these conditions can be neglected,” he says, “yet many local traditional opera troupes lack all of them.”

As such, the sudden catapulting of the small production team — made up of three smaller troupes from around rural Shaanxi — into the national spotlight has come as something of a shock to its members.

Of them, it is perhaps Jia Zhoufeng, the actor behind party secretary Wang Xing, who is most surprised about the play’s sudden trajectory into the limelight. The 38-year-old hails from Chengcheng County, an area in central Shaanxi whose economy has for years survived largely on China’s coal industry.

Over the 23 years since Jia began studying qinqiang at the age of 15, almost all his performances have been played out in rural communities around Chengcheng County, with a simple stage beneath his feet and a handful of villagers seated before him.

“Who could imagine an actor from the country could have such a beautiful voice?” asks Shi Yukun, the opera’s director.

Jia believes, on the contrary, that his country background has prepared him well for the role. All county-level opera actors like him, he says, have a “voice of gold” that is honed through countless performances at funerals.

Across vast stretches of China’s rural northwest, people will hire professional “mourners” to cry and sing at ceremonies for the dead. The grueling performances, nine hours at a time and stretched over seven days, result in strengthened vocal chords and improved tonal control.

“We have to do this to make a living,” Jia tells Sixth Tone, pointing to the inadequate income that performing with a local opera troupe would have brought him in former times. It is unclear what monetary benefits his new role in “Home” will bring him, but Jia can expect it to surpass the 260 yuan (around $40) he was making each month in 2001 or the 780 yuan per month he made in 2010.

Jia is lucky to find himself in a position where he will be performing on a national stage, says the opera’s artistic director Yu Qingfeng. Yu tells Sixth Tone that a great number of Chinese traditional opera actors, even of the smallest troupes in the remotest of areas, are as talented as Jia. As for who makes it big, it’s just a matter of chance, he says.

Attempts by the opera to garner government recognition and stimulate interest come decades after the country began encouraging state-owned drama troupes to move towards market-oriented business models. The movement, known in official jargon as the “structural reform of drama troupes,” began in the 1980s and came to a head in 2011 when the Ministry of Culture called on arts organizations around the country to speed up the process of decentralization.

Yet as dwindling interest in qinqiang illustrates, the liberation of such troupes from the hands of government hasn’t necessarily been good for the survival of the art forms themselves. Concurrently, the willingness of the government to give productions like “Home” the proverbial rubber stamp suggests that the government’s attempts to distance itself from the arts are not absolute.

Some experts think that becoming aligned with the government would be a death trap for the arts. Lu Xiaoping, a professor of dramatic arts at Nanjing University, tells Sixth Tone he believes free creation is the only path for traditional drama to reach true prosperity.

“Today’s system is co-constructed by the authorities and some artists,” Lu says of the troupes that pander to politics for financial security. “People with vested interests are sucking up all the resources from the government in this area, therefore killing the future of traditional drama.” There are plenty of other areas of the arts, he believes, that are just as if not more deserving of the government’s attention and checkbooks.

Naturally, those involved in “Home” disagree. Scriptwriter Xie Yanchun argues that the notion of toeing the party line doesn’t undermine the creative value of the work. “We are not engaging in flattery,” Xie tells Sixth Tone. “The play is adapted from a real event. In this case, there is no contradiction between artistic creation and political duty.”

The real event Xie refers to is a huge resettlement project of 3 million villagers across Shaanxi province, of which the story of Qiyan Village in “Home” is but a small part. The colossal migratory project began in 2011 as part of the government’s poverty alleviation campaign, relocating villagers to newly built towns at an overall cost of 100 billion yuan.

“This resettlement project is twice as large as the Three Gorges resettlement, yet far lesser-known,” director Yu says, referring to the mass relocation of over a million people to make way for the controversial dam in central China’s Hubei province. “As an art worker, I think it’s our obligation to represent this kind of beautiful thing in real life.”

For actor Jia, his ambitions are much less lofty. All he cares about is his performance being appreciated.

“Over the years, I have looked out at the audiences from the stage,” he says. “Audiences are shrinking, and audiences are aging.”

“I cannot help thinking that one day, there will be no one watching qinqiang at all.”

(Header image: Actors perform the ‘qinqiang’ opera ‘Home’ in Xian, Shaanxi province, 2016. Courtesy of Jia Zhoufeng)