How the New Gaokao Made My Son More Stressed

A couple of weekends ago, my son, Xiao Yu, took two of the new gaokao elective exams: one in physics, and another in biology. We are currently waiting for his scores to come out, which should happen at the end of April.

This was not the first time Xiao Yu had taken one of the subject tests, which are similar in content to the American SAT Subject Tests or the British A-Levels and count toward his overall gaokao score, which will determine which colleges he can apply for. According to Zhejiang province’s gaokao reform plan, every student from the second year of high school onward gets to select three subjects, on which they are tested in elective exams held separately from the gaokao.

A student may take each of these exams twice, and their highest scores will be entered into their overall gaokao scorecard. Xiao Yu took the physics exam in the second semester of his second year and the first semester of third year, scoring a weighted 97 out of a possible 100 points. Afterward, he was able to drop his physics class and spend more time focusing on his other subjects.

Xiao Yu attends one of Zhejiang province’s “key” high schools, located in the coastal city of Wenzhou, and his grades place him among the top 20 students in his class. He’s always liked science, and in the second semester of his first year of high school, when he began considering which elective exams he wanted to take, he ultimately decided on physics, chemistry, and biology.

As both a parent and a teacher, I believe that the new gaokao was designed with the best of intentions. As part of the education reforms, the traditional humanities-sciences divide in Chinese high schools was abolished. Classes in Chinese, math, and English remain mandatory, but students can choose their remaining three courses from a list of seven subjects: ideology and politics, history, geography, physics, chemistry, biology, and technology.

The idea is to give students more choice and reduce their academic workload by letting them choose what they want to study. Once they have taken an elective exam, they can drop the corresponding class and concentrate all their energy on the three mandatory subjects that make up the new gaokao exam.

The reform’s implementation has been rocky, however. Which courses should you choose? When’s the best time to take the test? Some will ace the test on their first try; does taking it twice put you at a disadvantage? How should you allocate your time between all of the tests you have to take? The new gaokao is just as much a test of students’ prioritization and decision-making skills as it is of academic ability.

When it comes to time management, the gaokao has gone from a one-off event to something more gradual. Giving students more opportunities to succeed is good, but it also means more pressure. Ever since he began high school, Xiao Yu hasn’t been able to relax, even for a second. In fact, he’s told me he thinks the old system was better. It was like ripping off a Band-Aid: Best to do it all at once and get it over with. Now, everything is much more muddled, with students preparing for one test, then another, and another — over and over again.

My son also participates in extracurricular math competitions, the timing of which often conflicts with the elective exams, making everything difficult to schedule. If a student’s first attempt at an elective exam conflicts with a competition, it may be better to focus on the competition, even at the expense of the exam — because competitions only take place once, and are sometimes seen as more important than exams.

The new system also impacts how coursework is planned. Xiao Yu was able to stop taking physics last fall, after finishing the elective exam, but most technology-oriented universities require students to take a university-designed physics test in addition to the standardized exam. If students drop these classes too soon, the long gap in their studies could potentially have an impact on their ability to major in fields related to science and engineering or physics.

Students have a more relaxed schedule between April and June, and after finishing their last elective exams in April of their final year, they shift their attention toward the three mandatory courses that will appear on the gaokao. This strategy has drawbacks of its own, however. Some students spend too much time preparing for their subject tests and neglect their Chinese, math, or English coursework.

Their subject teachers complain that it’s impossible to cram the needed material into such a short period of time. Teachers of Chinese, especially, note that the knowledge of the language necessary to pass the gaokao takes years to learn. In addition, the work needed to prepare for the elective exams can have a negative impact on the ability of these teachers to plan their own curricula.

Furthermore, the use of weighted scores has caused additional controversy. Physics is a relatively difficult subject, and as an elective course, it tends to attract the strongest students. As a result, competition among those taking the exam is fierce, making a perfect weighted score harder to achieve. Meanwhile, far fewer students choose to take the technology elective exam, which is a new addition to the gaokao this year.

In other words, a strong student who chooses to take the technology elective exam has a much easier path to a perfect weighted score than one who opts for physics. This leads to questions of fairness when it comes to weighted scores. It is impossible to compare the different subjects, and yet the gaokao is ultimately based on a universal points scale, and all students, regardless of what subjects they choose, are measured according to the same standard.

Zhejiang’s new gaokao is at the forefront of a nationwide movement, one which aims to reduce student workloads, give them more control over their education, and get them started thinking about their future career path during their first year of high school. As part of this drive, significant changes have been made to the selection process for university majors, allowing students to choose up to 80 combinations of major and university — far more than the five schools and six majors they were allowed to request under the old system.

As a parent, I applaud this initiative, but I also hope that education officials will move quickly to fix any problems that pop up in the new system. While every new reform has teething problems, it’s essential to prioritize the education and well-being of our children above anything else.

Translator: Kilian O’Donnell, editors: Yang Xiaozhou and Matthew Walsh.

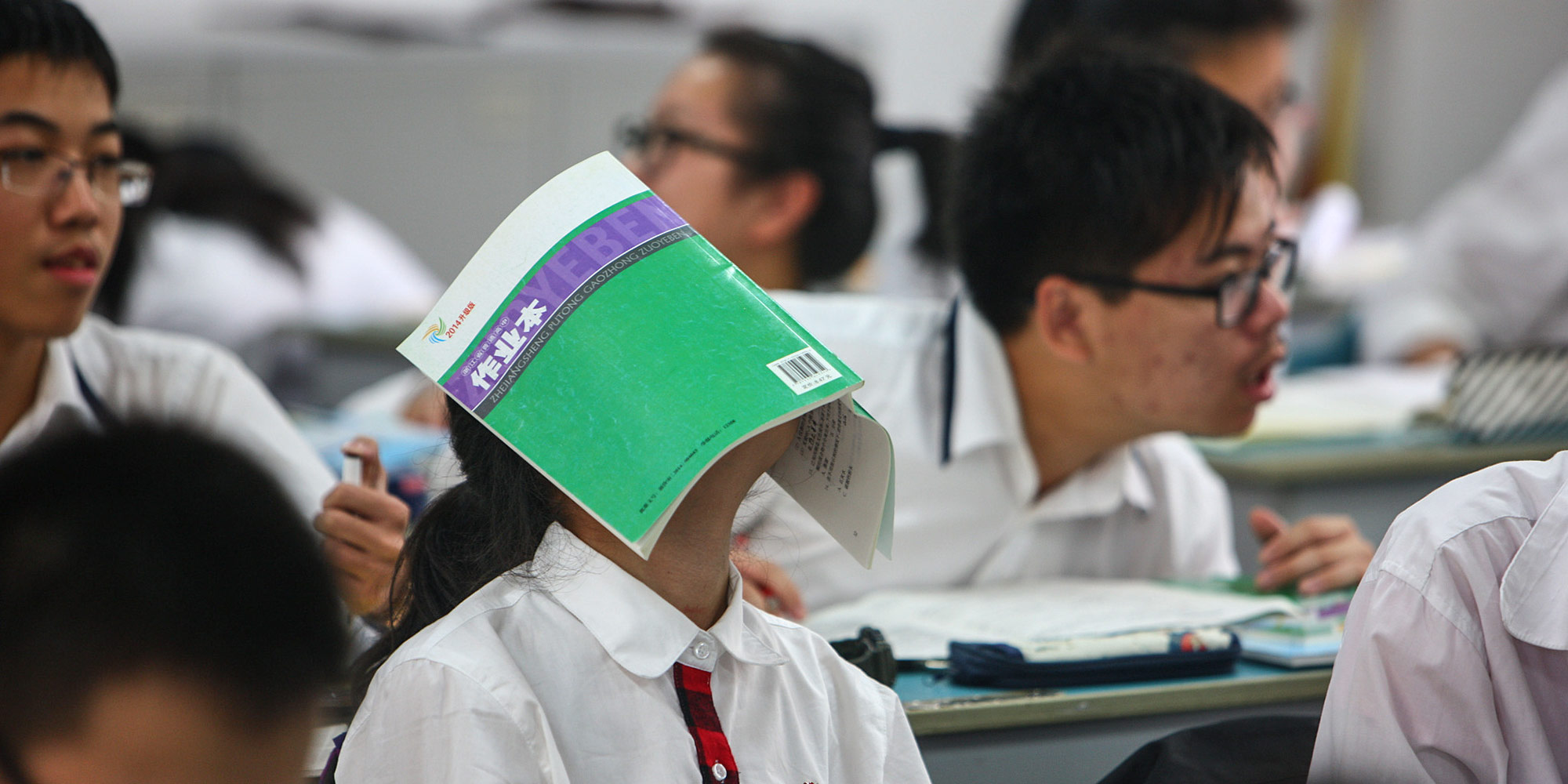

(Header image: A student rests with an exercise book covering her face at a high school classroom in Ningbo, Zhejiang province, Sept. 24, 2014. Zhang Peijian/VCG)