How Laos’ Black Market Undermines China’s Ivory Ban

VIENTIANE, Laos — As tour buses pull up in front of San Jiang Market, not far from Wattay International Airport, a guide beckons to a group of Chinese tourists. They soon disappear into the jungle of shops bearing signs in Chinese characters, many of which sell “local specialties,” or any illicit wildlife product imaginable.

From elephant tusk, rhinoceros horn, and tiger bone to shells of the critically endangered hawksbill turtle, most of these products are displayed openly on store shelves here, despite being subject to longstanding controls or bans on their trade.

“Bringing a few [pieces] back isn’t a problem: Just hang them around your neck or wrist, and customs won’t give you any trouble,” the owner of a shop called Hero Company told a reporter from Sixth Tone’s sister publication, The Paper, posing as a buyer. The shopkeeper, surnamed Wang, runs a store specializing in mahogany furniture but nevertheless had several small, carved pieces of ivory and rhinoceros horn exhibited prominently in a display case, visible from the entrance. Like many shopkeepers in San Jiang, Wang is Chinese and primarily sells to Chinese buyers.

For centuries, ivory and other wildlife products have been used both in medicine and as markers of wealth in China and elsewhere, and the demand for these goods has led to a rise in poaching. Since 2002, monitoring programs under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) — which seeks to protect endangered species by banning or controlling certain wildlife products — have identified China as the largest market for illegal ivory in the world.

The Chinese government has agreed to close all remaining domestic legal ivory markets by the end of 2017. This decision has been hailed as a milestone in Chinese efforts to combat elephant poaching, but the black market trade in illegal wildlife goods in a neighboring country may undermine such measures.

The proliferation of wildlife trafficking in Laos has been an open secret for some time. Although Laos joined CITES in 2004, the country has since received numerous sanctions for its inability to enforce the convention’s provisions.

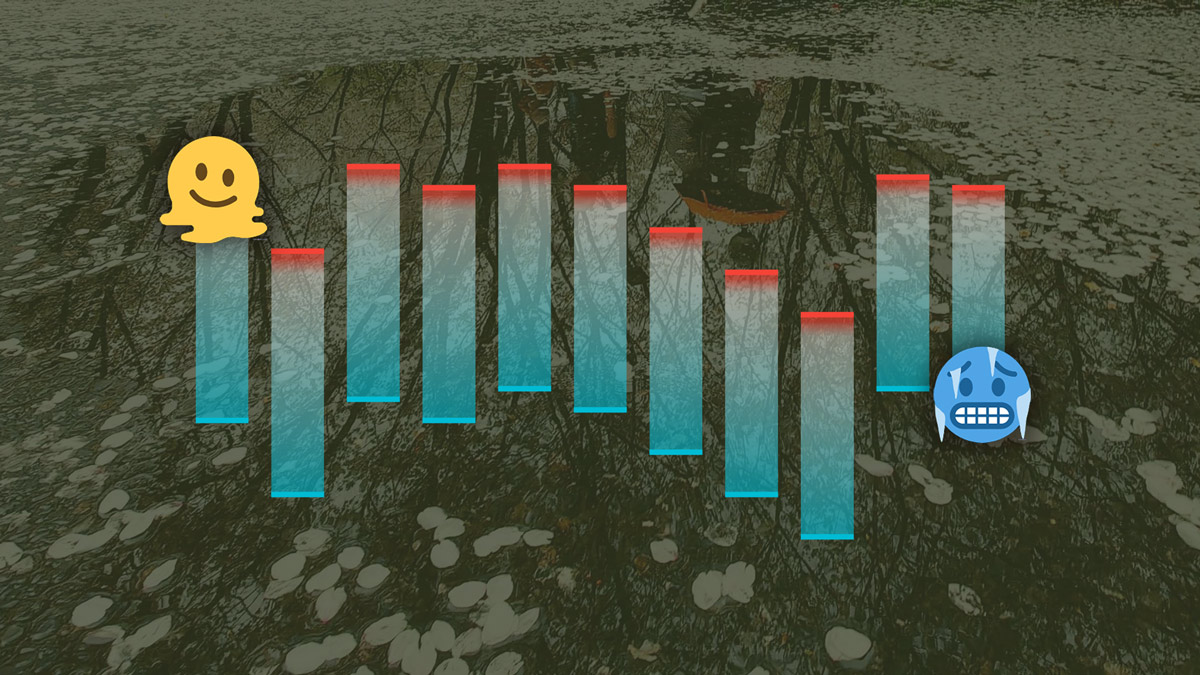

While Asian elephants are also poached for their tusks, environmentalists believe most ivory traded in Asia comes from Africa. Whether in Africa or Asia, poachers remain one of the greatest threats to the continued survival of elephant and rhinoceros populations. A survey of African elephants carried out in 2016 revealed that in less than 10 years, poaching and habitat destruction were responsible for the deaths of 140,000 elephants.

It is even harder to be optimistic about the fate of the rhino. In South Africa, which has the largest rhino population of any nation on earth, poachers have killed over a thousand rhinos every year since 2013, and the overall population has been shrinking at an annual rate of 10 percent. In Asia, rhino horns are often added to traditional medicines or used to make luxury goods. The international community banned the trade of rhinoceros horn as early as 1977, but on the black market, its price has surpassed that of gold.

According to surveys by international groups, a kilogram of illegal ivory sells for $150 in Africa. After being traded and carved, the ivory is worth 10 times the original sale price in China. Rhino horn can be sold for 400 times its original price.

The businessmen operating out of San Jiang Market are clearly familiar with the international and domestic regulations governing their trade, as well as the extent to which they can ignore the rules. Wang confided that all of the products on display at Hero Company were illegal, but said that “in Laos, no one cares.”

San Jiang Market is not the only place in Vientiane where this illicit trade is carried out in the open. Shops, mostly run by Chinese, can be found inside luxury hotels and in bustling downtown districts. These store owners are not only willing to provide detailed instructions to buyers on how to avoid customs inspections at airports and borders; they also do their best to expand their networks using popular Chinese messaging app WeChat, in hopes of attracting repeat customers. Through the app, buyers can view items that a shopkeeper posts and purchase or reserve the ones they like. The store will then ship the items directly to the customer’s door.

According to many involved in the trade, some delivery and logistics companies have their own channels for getting restricted items across the Chinese border. At Hero Company, a number of cardboard boxes are stacked by the entrance; according to shop owner Wang, they are filled with ivory bound for China, to be shipped to customers who either did not want to carry the ivory themselves or bought too much to wear all at once. “Shipping takes skill, but we offer door-to-door delivery and guarantee the goods against damage or confiscation,” said Wang. As he spoke, he pulled out a pile of completed delivery slips and waved them around, as if to prove the veracity of his words.

The owner of handicrafts shop Fuyuan Pavilion, surnamed Peng, said that most months, he ships about 20 kilograms of ivory products to China. During peak periods, he might ship as much as 90 kilograms.

Many of the international environmental groups that have conducted surveys of wildlife trafficking in Laos have expressed their disappointment at the situation there. As a link on this illicit trade chain, Laos is ideally located, sharing long, porous borders with China, Vietnam, and Thailand. Traditionally, all of these countries used wildlife products for medicinal purposes or in luxury goods.

“Laos is a transfer point on the supply chain,” explained Steven Galster, director of the Freeland Foundation, which campaigns against wildlife trafficking. Galster said that neighboring countries are the primary consumer markets, as the domestic market is limited by local income levels.

According to a long-term study performed by Galster’s organization and published by The Guardian in 2016, wildlife trafficking receives support from high-level members of the Lao government in return for a 2 percent “import tax.” This trade led to the deaths and injuries of 16,000 elephants, 650 rhinos, and 165 tigers in 2014 alone. The publication of the group’s study did not result in the investigation of a single wildlife trafficking organization.

It isn’t hard to find examples of wildlife trafficking within Laos. Wildlife trade monitoring network TRAFFIC, together with the London-based Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), revealed the widespread nature of wildlife trafficking in the Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone, located on the China-Laos border, as well as in northern Luang Prabang province. Businesses there openly offer tiger bones, elephant tusks, bear paws, and other products to thrill-seeking tourists, mostly Chinese.

After this illegal trade was exposed in 2015, the Lao government shut down a number of culprits and confiscated their wares. However, according to TRAFFIC and the EIA, wildlife trafficking in the region has already recovered.

The Paper requested an interview with the Lao government regarding wildlife trafficking, but as of publication time had only received a letter from the public relations department of the Lao Ministry of Foreign Affairs saying the request was under consideration.

On Laos’ eastern border, Vietnam is becoming an increasingly vital stop in the global black market for ivory, according to a 2016 survey conducted by Save the Elephants. The Kenya-based organization says that about two-thirds of poached African ivory will eventually end up in either China or Vietnam — but while the Chinese market for ivory products is gradually shrinking, Vietnamese demand continues to grow.

Numerous San Jiang Market store owners said they primarily purchased their raw ivory and rhinoceros horn from Vietnamese dealers, who either smuggled the goods across the border themselves or relied on relatives. One San Jiang shopkeeper said he had purchased two elephant tusks from a Vietnamese dealer a day earlier, but he would only show pictures. “I don’t dare keep pieces of uncarved ivory that large inside my store right now,” he said.

A young seller from Vietnam, surnamed Vuong, told The Paper that she joined the trade after coming to Vientiane four years earlier as a tourist. “When I realized how many Vietnamese were in the business,” she said, “I thought to myself, why can’t I make a little money, too?”

To expand her business, Vuong opened a new shop near San Jiang Market. Viewed from the outside, the shop is an inconspicuous purveyor of mahogany furniture — but once inside, Vuong locked the door, went behind the counter, and proceeded to pull out roughly a hundred amulets and prayer bead bracelets, all carved from ivory. Shipping to China was available, and she said she regularly sells to a buyer in Kunming, southwestern China.

“If you’re really looking for something, then go with this,” Vuong said, grabbing a box of ivory Buddhist amulets. “They’re small and perfect for gifts, and you can wear several at a time.”

A Chinese version of this article first appeared in Sixth Tone’s sister publication, The Paper.

Translator: Kilian O’Donnell; editor: Kevin Schoenmakers.

(Header image: A sculpture decorated with ivory stands near a pile of elephant tusks, Kenya, April 28, 2016. Thomas Mukoya/ Reuters/VCG)