How Potty-Mouthed Online Advertisers Target Young Chinese

Recently, in a bid to capture consumers’ attention, China’s online retailers have become more and more daring in their advertising. Online commercials are a far cry from their print media counterparts, often breaking long-standing taboos and embracing vulgar, violent, or sexual language.

One commercial that appeared on e-commerce platform JD.com around the Singles’ Day shopping festival last November read: “Any festival without gifts is a dark day indeed! People need clothes like a horse needs a saddle — are you worth less than a common beast?” Another, featured on a similar website called Tmall, blared, “Love: It’s not just how you say it, it’s how you do it.”

While China has relatively stringent regulations on language that can and cannot be used in advertising, the internet is notoriously hard to police. At present, however, following the continual expansion of online shopping and the increasing competitiveness of e-merchants, advertisers have begun to break linguistic taboos — phrases that cannot be freely spoken or written because they are inconsistent with public morals or what is considered good taste. Their commercial use, in turn, has led to the deconstruction of these taboos.

This deconstruction manifests itself in two ways. First, advertisers may directly use taboo language in their advertisements. One of the slogans above encourages people to buy clothes, drawing attention to words like jiri, or “dark day,” which is considered an inauspicious way of referring to the anniversary of someone’s death.

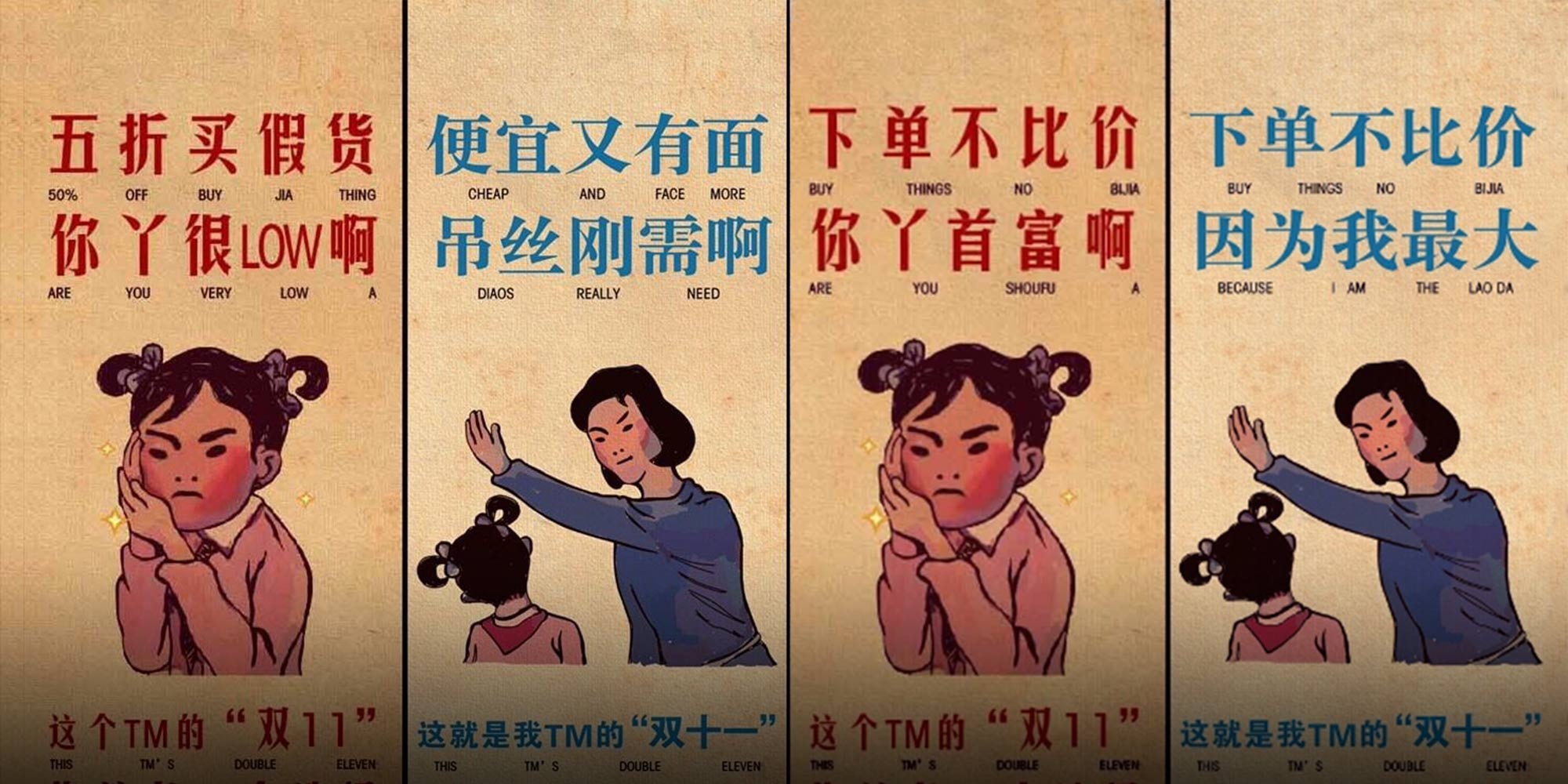

Meanwhile, chusheng — translated here as “beast” — is a personal insult. Playful appropriations of offensive language abounded around Singles’ Day, with electronics giant Suning “chastising” shoppers on online platforms Tmall and Taobao, two well-known haunts of purveyors of fake goods. “What, are you crazy?” the commercial lamented, repurposing the term niya, a condescending form of address. “Buying fake goods at half price? Damn, that’s a low move!”

Other ads went even further. “Taking 618 by storm!” declared a banner on JD.com, referring to the inaugural shopping festival hosted by the platform last June as a competitor to Singles’ Day. The internet behemoth’s erudite wordsmiths finished with an expletive flourish: Wo kao, qiang a! — roughly meaning “Fuck, click while you can!”

By showing flagrant disregard for linguistic taboos and breaking with established etiquette, advertisers have exploited the positive functions that these taboos can serve in our social interactions. First of all, breaking taboos is a great way to seize consumers’ attention. Second, their use shortens the perceived social distance between consumers and advertisers, because taboo language is generally used between close friends and often denotes a degree of intimacy between speakers. Finally, when used in the right context, linguistic taboos can make certain phrases sound more emphatic and impressive.

Another way in which linguistic taboos have been deconstructed in advertisements is when, instead of directly using explicit language, advertisers use puns or double entendres to hint at taboo notions and make consumers laugh. This is the case with another abovementioned slogan, “Love: It’s not just how you say it, it’s how you do it.”

This advertisement plays on the dual connotations of the verb zuo, “to do” or “to make.” It simultaneously hints both at the notion of sex and at something much more innocuous. Puns allow advertisers to convey the erotic connotations of intimate or taboo sexual language without explicitly using it in their advertisements. Beyond merely marketing a product, their purpose is to convey fashionable, innovative ways of thinking.

Three Gun, a men’s underwear brand whose Chinese name is pronounced san qiang, adheres to linguistic taboos in some commercials but breaks them down in others. One of the company’s more innocent commercials reads: “100 percent cotton, classic fit, long-lasting material. A trusted brand.” Another ignores practical information about the product completely: “Chinese bros who buy local always go for Three Gun. Bang, bang, bang!”

The second advertisement draws attention, unsurprisingly, to the onomatopoeic phrase “bang, bang, bang.” Its Chinese form — pa pa pa! — is, like the English phrase “banging,” a vulgar term mimicking the sound of vigorous sexual intercourse, commonly used online and popular among young people.

The proliferation of taboo-breaking advertisements is hardly surprising given the leading demographics of online shoppers: young, white-collar professionals with mid-range incomes, as well as high school and university students. In everyday communication, these groups tend to look down on linguistic conventions and seek to subvert them by creating new and surprising turns of phrase. Advertisers try to desensitize consumers to taboo language in order to cater to the linguistic preferences and social norms of these groups. As far as these young people are concerned, subversive language expresses their individual identities and provides them with a sense of belonging.

When I was a graduate student, I undertook a survey to research how advertisers broke deep-seated linguistic taboos and which groups of consumers found them socially acceptable. I found that traditional advertising that does not make use of taboo language is generally accepted by more than 90 percent of both young and middle-aged consumer groups. Online advertising that explicitly uses taboo language, meanwhile, is acceptable to just a little over 20 percent of people in the same groups. On the other hand, commercials that rely more on rhetorical devices such as double entendre are far more acceptable among young consumers — more than 60 percent of them, in fact — while only 30 percent of middle-aged consumers tolerate them.

Taboo-breaking advertisements tend to be released around made-up consumerist holidays such as Singles’ Day and 618. For this reason, young consumers take part in these shopping festivals with a greater degree of enthusiasm than their older counterparts. Therefore, advertisers compete with one another to create slogans that will attract young people, while at other times of year, such advertisements are far less common.

But why is it that so many young people prefer innuendo-based advertising? The answer may be that advertisers have underestimated just how deeply entrenched linguistic norms are in Chinese society. Despite the partial subversion of these linguistic taboos, the older generation still feels constricted by rules governing what can and can’t be said. Words such as jiri, chusheng, niya, and wo kao already tend to make people feel uncomfortable in private conversations. Their social functions can only be exploited within the context of an extremely intimate relationship, one that fundamentally cannot exist between a business and a consumer.

Advertising that challenges our deep-seated taboos is the product of a postmodern consumerist society and culture. The language used in these commercials hints at a grassroots rebellion by young people who wish to subvert traditional culture. However, the possibility remains that by blindly exploiting the shock value of linguistic taboos and by attacking cultural and moral values through language in ads, advertisers will lock themselves in a race to the bottom that alienates — rather than attracts — the very young people whom they are courting.

Translator: Lewis Wright; editors: Lu Hua and Matthew Walsh.

(Header image: A 2014 advertisement for electronics giant Suning, which contained some Chinese curse words. Courtesy of the author)