Plain Stories: The Tibetan Director Eschewing the Exotic

SHANGHAI — For many outsiders, be they from China or abroad, Tibet is either an unearthly paradise sitting atop high mountains and shrouded in mist, or a region defined by an ongoing rift with the central government. But to Pema Tseden, a Tibetan filmmaker who made China’s first Tibetan-language feature film, there’s another story to tell.

Born to a nomadic family in Qinghai province’s Hainan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in northwestern China, 47-year-old Pema Tseden has devoted more than half his life — first as a novelist and then as a director — to telling stories of Tibetans’ everyday realities, no matter how quotidian they may be. “My films are told from the perspective of my own people,” Pema Tseden told Sixth Tone in his Shanghai hotel room, where he was staying during the city’s international film festival in June.

Frustrated with the prevalence of movies that either romanticized Tibet or glossed over its complexities with China’s mainstream political correctness, Pema Tseden began making films in 2002, seeking to offer an insider’s view of the struggles that his people face. Since then, his documentaries and feature films — the latter often starring untrained actors in leading roles — have revolved around a common dilemma: the simultaneous desires to preserve traditional culture and modernize.

Seen by many as the face of a new wave of Tibetan cinema, Pema Tseden’s standing in domestic and international film circles has risen, and he has shouldered a new responsibility: encouraging more young talent from his homeland to pick up the camera and tell stories of Tibet in their mother tongue.

With this mission in mind, Pema Tseden attended this year’s Shanghai International Film Festival not as a director himself, but as the executive producer for two young Tibetan directors’ movies: one a documentary about three Tibetan girls trying to make it as hairdressers, and the other a drama about a killer’s search for forgiveness through Buddhism. Such Tibetan-language films face significant challenges when trying to enter the mainstream market, which favors Mandarin Chinese movies, says Pema Tseden.

The surprising box office success this year of director Zhang Yang’s “Paths of the Soul,” a film made in 2015 that documented 11 Tibetans’ 2,000-kilometer pilgrimage on foot, bolstered hopes for the mainstream market potential of Tibetan-language cinema, with the film raking in almost 100 million yuan (around $15 million). Pema Tseden appreciates Beijinger Zhang’s efforts to immerse himself in the culture he was documenting, but he speaks less favorably about the addition of certain plotlines. “I think it would have been better if he had just stuck to documenting reality,” he says.

Pema Tseden spoke to Sixth Tone about the need for cinematic storytelling from the perspective of Tibetans themselves, the opportunities and challenges facing Tibet’s young filmmakers, and the threat that cultural assimilation poses to artistic exploration. The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Sixth Tone: Your movies have been celebrated as heralding a “new wave” of Tibetan cinema, one that speaks from the perspectives of Tibetans themselves. How do you feel about this term?

Pema Tseden: I think it’s hard to form a “new wave” — it’s nothing like the French New Wave [of the ’50s and ’60s] in terms of scale and thinking.

Movies about Tibet used to either belong to the politically correct mainstream or come from the perspective of outsiders, be they from China or further afield. My films are told from the perspective of my own people. If everyone thinks that this is something different, then it’s OK for them to use the word “new.”

No matter whether it’s through writing novels or making films, my ultimate goal is to create. Dealing with the topics that concern you personally makes you want to both express yourself through your work and document the way of life of Tibetans accurately. These things make my movies different from other films, but I don’t seek that contrast intentionally.

I think that other movies essentially seek the exotic. They have a similar mindset to many tourists: They go for a fleeting glimpse of a place, with neither real understanding of the culture nor emotional attachment to the people who live on the land. But in the past few years, I have seen some changes in the creators themselves. They might not be able to immerse themselves deeply, but nonetheless, they are sincere in their intentions and are able to observe in a calm and collected way.

Sixth Tone: What, then, do you make of the hugely popular film “Paths of the Soul” by Zhang Yang, which tells the story of Tibetan pilgrims?

Pema Tseden: I think that regardless of whether he truly understands the phenomenon and was able to enter their hearts, Zhang’s attitude is sincere. I appreciate that he was able to buckle down and stick with these people throughout their spiritual journey.

He also did something experimental with this documentary in that he added a storyline. As I see it, the additional plot stood out and added a sense of artificiality. I think it would have been better if he had just stuck to documenting reality.

Sixth Tone: Does your decision to make all your films in the Tibetan language mean that Tibetans are your target audience?

Pema Tseden: I don’t shoot films to be viewed by Tibetan people alone. With “Tharlo,” for example, I wanted the film to reach more people, and so I found suitable audiences through channels like film festivals.

Things have changed. When you make movies today, you have to embed an international perspective. It’s no longer the case that film festivals will want you as long as your movie is about Tibet. If you want to go to a good festival, you have to demonstrate innovation in cinematic languages and global expression.

Sixth Tone: You attended this year’s Shanghai International Film Festival not as a director but as an executive producer in support of young Tibetan directors. What are your thoughts on the future of Tibetan cinema?

Pema Tseden: It’s still early days for Tibet’s movie and TV business. Many people are developing an interest in it, including some very talented young people. I have seen some good screenplays — and that’s why I’ve focused on production this year.

In terms of storytelling, both knowledge of our ethnic group and professional skills are of equal importance. It worries me that some Tibetan kids grow up entirely in cities and are no different from Han people. Assimilation is a problem not only with metropolitan kids. Children will choose whether to focus on the Tibetan language or whether to focus on Mandarin Chinese or English based on practical concerns — it’s possible that you’ll have more opportunities if you study Mandarin or English.

I hope young filmmakers can have breakthroughs and achievements in their art. If they take the path of making commercial films, they will face many more restrictions. There are challenges at every level of the creative process — pressure comes from both censorship and the need to raise funds. The domestic market is essentially a Mandarin Chinese market; for ethnic minority films wishing to enter it, there are challenges.

We are off to a good start. There will be more opportunities to come.

Editor: Owen Churchill.

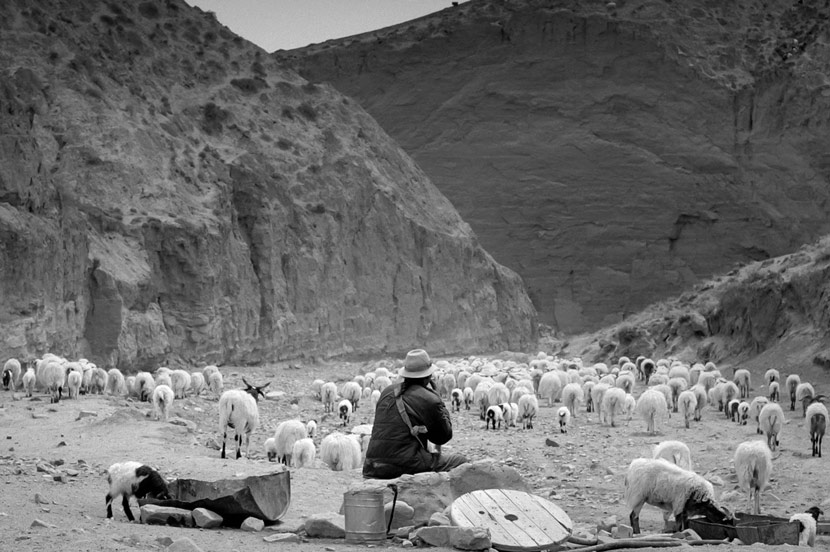

(Header image: A still frame from the film ‘Tharlo.’ Courtesy of Pema Tseden)