Titanic’s Chinese Survivors Resurface From Depths of History

SHANGHAI — More than a century after the Titanic sank in April 1912, few new stories surface from the wreck. When documentary filmmaker Arthur Jones and his team started work on “The Six” — their film about the ship’s six Chinese survivors — in 2012, they kept expecting to find that someone else had already told the story.

Yet the history of the Chinese passengers who escaped the Titanic has largely been forgotten, even in their homeland, as discriminatory U.S. immigration policies and a cultural imperative of self-effacement combined to obscure their tale.

“There is something that really is quite Chinese about that: Essentially, don’t raise your head too far above the parapet because you will get shot down,” Jones told Sixth Tone from his Shanghai studio. “I think that a confluence of these two factors means that out of several hundred people, they were the only ones who never told their stories.”

The odds were stacked against them: The average survival rate for men in third class was just one in six. But when disaster struck, being a poor sailor with limited English turned into an advantage for the eight Chinese men onboard — and six of them survived.

All eight Chinese men hailed from southern China. They had previously worked on cargo ships traveling between China and Europe, and they likely intended to migrate to the U.S. to start a new life. They boarded the Titanic in Southampton, England, on a single ticket listing eight names — a common practice for third-class passengers. Like other unmarried third-class men, they were housed in windowless cabins in the bow of the ship.

When the ship struck an iceberg, the men living in the least desirable conditions saw the gravity of the situation with their own eyes. Freezing water flooded into their living quarters, while on the upper levels, the crew were still reassuring first- and second-class passengers that nothing was amiss. Relying on their own survival skills, the Chinese sailors would have reacted quickly to evacuate the ship, Jones said — especially since they likely did not understand orders in English to stay in their rooms.

Five of the six Chinese survivors made it directly onto lifeboats, while the sixth, Fang Lang, was one of the few lucky people picked up by Lifeboat 14, the only vessel to return and search for survivors.

The six men’s lucky escape is little-known in China, despite the popularity of the Titanic story in the nation: James Cameron’s 1997 feature film, “Titanic,” was released in China the following year and earned close to $44 million at the Chinese box office — and soon, the southwestern province of Sichuan will have its own life-size replica of the ship. One theory to explain the film’s appeal in China, first put forward in a commentary in Party newspaper People’s Daily, claims that Chinese audiences are particularly drawn to romance between a poor man and a rich woman.

Jones estimated that 90 percent of the Chinese people he spoke to about his project didn’t know there were Chinese passengers on the ship. The remainder had another impression entirely: “Oh yeah, I heard about those guys; they were very dishonorable,” Jones recalled people saying.

A rumor that the men had disgraced themselves by sneaking onto a lifeboat meant for women and children persisted in China and abroad, and it was all that most people knew about the Chinese survivors. When Jones’ team reached out to the company building the life-size replica of the Titanic in Sichuan, employees were initially reluctant to help memorialize the six passengers, repeating the allegation.

The rumor may have originated with Titanic owner J. Bruce Ismay, who ended up in a lifeboat with four of the Chinese men. Ismay faced questions about the legitimacy of his own place on the boat, as he had declared that the ship was unsinkable and neglected to provide enough lifeboats.

At the post-incident inquiry in New York, Ismay claimed that the Chinese men were found stowed away under the seats after the lifeboat cleared the Titanic. But records show that the boat was guarded by an armed officer, with no opportunity for unauthorized passengers to slip aboard. Steven Schwankert, the lead researcher for “The Six,” told Sixth Tone that he believes Ismay’s insinuation was an attempt to “reinforce his own status as a gentleman.”

If this was the case, Ismay’s attempt to save his own reputation may have served to sully those of the six Chinese men for over a century. The team behind “The Six” hope that when their film airs on Chinese television in 2018, it will finally put an end to the doubt that was unfairly cast over the men’s characters.

Jones speculated that the men could have simply been squatting down between the seats. “That would make complete sense if you know anything about China or Chinese laborers,” he said, as it is common to see Chinese workers resting in a squatting position.

In fact, basic knowledge of China is an important element that Jones and his Shanghai-based team have brought to their research. Others who have tried to trace the men’s plight hit a stumbling block when they were unable to connect the individuals’ Chinese names with the misspelled transliterations that turned up in American and British records.

As Jones and a dozen researchers searched for descendants of the six men, they began to recognize a pattern: The survivors had not told relatives born outside of China about their experience.

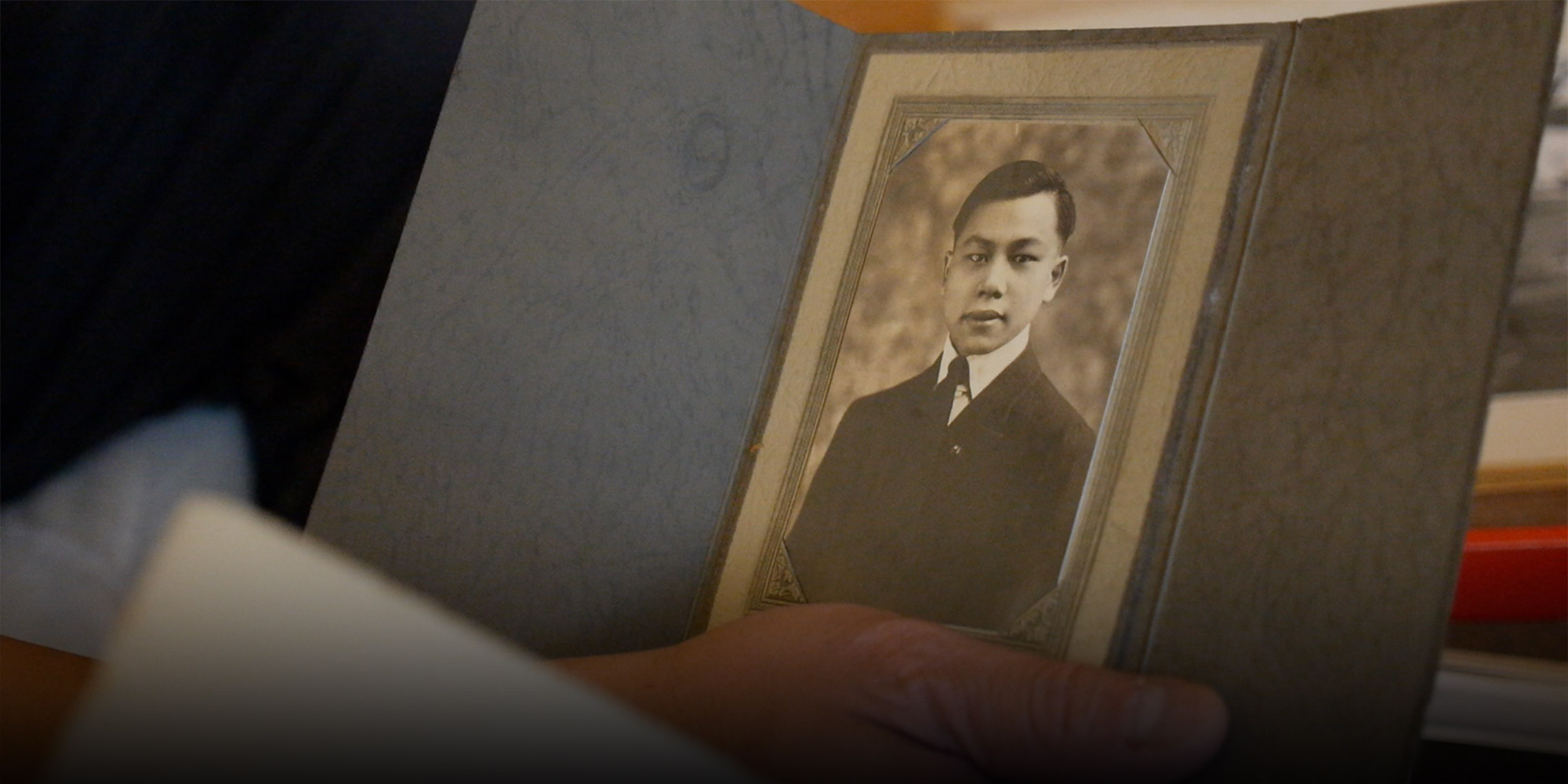

Fang’s story is particularly harrowing: He was found floating on a door to which he had tied himself. After he was pulled — freezing — from the wreckage, he tirelessly rowed the lifeboat to safety and was praised for his efforts, according to accounts that Jones and his team collected. The 1997 film recreated Fang’s rescue, but the scene was not included in the final cut. He never said a word to his son, Tom Fong — who appears in “The Six.”

The six men survived the sinking of the Titanic only to arrive in the U.S. during the Chinese Exclusion Act. The act, which stretched from 1882 to 1943, prohibited immigration of Chinese laborers to the States and cast Chinese workers as scapegoats for the nation’s economic woes. While other passengers were welcomed in New York and given the opportunity to recount their stories to the press, the six Chinese survivors only made it as far as Ellis Island before being deported within 24 hours and disappearing from the record — though some, like Fang, eventually made their way back to North America.

“One of the side effects of the way that they were treated was that they were always in fear of being found out, being deported,” said Jones. “It just appears that Fang Lang never felt safe enough to tell his story.”

Editor: Qian Jinghua.

(Header image: A still frame from the documentary ‘The Six’ shows a photo of Fang Lang in his youth. Courtesy of LP DOCS)