For Chinese Women, Getting Pregnant Can Be a Fireable Offense

BEIJING — When Li Mengyuan walked out of the labor arbitration office on a Monday in October, the 32-year-old didn’t feel like a winner — even though the dispute with her former employer over maternity benefits had been decided in her favor.

Now with a 1-year-old in tow, Li belongs to a group that Chinese companies are increasingly reluctant to employ: new moms. “I have to look for another job, and potential employers might be concerned about my new mother status, and whether I’m considering a second child,” Li told Sixth Tone.

In the past two decades, China has strengthened its employment protections for new mothers, prohibiting companies from terminating contracts or reducing salaries of employees who take time off to get married or have children. Employers are also required to provide a maternity allowance that varies based on salary, as well as 98 days of maternity leave — in accordance with International Labor Organization (ILO) standards — though most local governments stipulate 128 days of leave.

Yet this legal progress has placed a significant financial burden on employers, leading to labor disputes over compensation and even dubious hiring tactics to sidestep maternity costs altogether. Some companies have become more selective in hiring, grilling employees about their marital status and pregnancy plans — or giving preference to male applicants outright.

In the first eight months of 2016, a large proportion of the 1,273 cases female employees filed with the labor arbitration office in Beijing’s Dongcheng District had to do with being underpaid or getting fired during the pregnancy, maternity leave, or breast-feeding periods, according to the All-China Women’s Federation. “Supporting the salaries and welfare benefits of a new employee who will be absent from the office for at least four and a half months is no small expense for any company,” explained Xu Rongxing, a human resources manager at a medium-sized multinational company in Shanghai.

In Li’s case, all seemed to go according to procedure at first. She was forthcoming about her plans, announcing her pregnancy seven months after she joined the private media company in early 2015. She was given 128 days of maternity leave and was able to collect a maternity allowance — part of a social security fund including pensions and health insurance that companies are required to set aside for every employee. The state helps fund the latter benefits but not maternity allowances — unlike in countries such as Sweden, whose government subsidies for maternity benefits account for a whopping 1.8 percent of total government expenditure.

In theory, China ranks reasonably high in international assessments of maternity provisions. The nation was among the 45 percent of countries included in a 2014 ILO report that provide benefits amounting to at least two-thirds of earnings for at least 14 weeks. But in practice, some Chinese employers will do anything to circumvent their legal responsibilities.

For Li, the problems began after her maternity leave ran out and she hadn’t yet found a child care solution. She decided to extend her absence, taking additional unpaid leave for around five months. The company was less than pleased but had no choice but to keep her on their books: Chinese labor law also stipulates that companies cannot fire female employees during the breast-feeding period, defined as the child’s first year.

Li returned to work in May of this year. Two months later, when her son turned 1, her contract was terminated, and she was ordered to pay the more than 30,000 yuan ($4,500) in social insurance contributions that the company had provided over the previous year. Though the labor arbitrator ultimately determined that she didn’t have to compensate the company, the decision was little comfort to Li. “I’m not the first woman to be treated this way for giving birth,” she said. The native of northern China’s Hebei province has yet to find a new full-time job.

Neither is her case unique in terms of its verdict, according to Li’s lawyer, Wu Pengyi. “It’s common for labor arbitrators to protect the interests of individuals over employers unless companies have written rules or legal evidence to prove the faults of their employees,” Wu, who specializes in labor disputes, told Sixth Tone.

Some companies hope to pre-empt such disputes altogether by including marriage and pregnancy plans in their informal hiring criteria. This scrutiny has become a greater concern for women in their 20s — the average age to have children in China is 28 — since the nation’s two-child policy took effect last year.

“The upgraded legal protection for female employees has made employers more cautious when they recruit,” said Xu, the HR manager.

As much as 54.7 percent of women reported being asked about their marriage and baby plans during job interviews in an All-China Women’s Federation survey of nearly 10,000 families from the beginning of this year. In the same survey, 12.5 percent of the women said they were fired shortly before proceeding with pregnancy plans.

Some women hide their family plans from employers to secure a position — in rare cases, even hiding an existing pregnancy. HR manager Wen Xinran recalls one such case involving a receptionist at her company, a Sino-German creative design firm in Beijing with around 30 employees. Weeks after the 24-year-old joined in early 2016, she began asking for sick leave. When the woman announced she was four months pregnant, she had been at the company for less than two months. The rest of the staff were shocked, said Wen.

“At small companies and startups, we need to maximize the efficiency and value of each of our employees. We cannot afford to spend money on someone who joins and immediately takes one year of paid leave,” Wen explained.

As Chinese law doesn’t require female employees to give advance notice of a pregnancy — and the company hadn’t asked during the application process — the woman hadn’t technically done anything wrong. But staff felt they had been duped. According to Wen, the receptionist decided to quit shortly after her maternity leave. “We did use some methods to ‘convince’ her to resign,” Wen admitted: The new mother was warned that she would be transferred to another post in the administration department that would require frequent business trips.

Now, though the firm does not officially discriminate during its application process, it has a different outlook on hiring. “We now tend to recruit male applicants or women who are already married with children,” said Wen.

The lawyer, Wu, sympathizes with women who aren’t forthcoming about their plans to have a child. “Hiding one’s pregnancy status can be regarded as a dishonest act, but it can also be interpreted as the way a woman protects her employment rights,” Wu said. Maternity benefits are only provided to employed women and are often the only source of income for young mothers during this period. In Shanghai, maternity benefits range from just over 10,000 yuan to more than 60,000 yuan per pregnancy, calculated based on the employee’s pay and the average salary at the company.

The apparent clash between employers’ interests and women’s employment rights can be resolved, according to professor Li Mingshun of China Women’s University — but it could take an overhaul of the country’s maternity allowance system. “The cost of women giving birth should be the responsibility of society as a whole, not individual companies,” Li Mingshun — no relation to Li Mengyuan — told the official judicial newspaper Procuratorate Daily.

The government should cover most of the cost of maternity benefits for all women regardless of employment status, said Li Mingshun. Other measures to reduce employment discrimination against female applicants could include offering tax incentives to companies that recruit a certain percentage of female employees or leveling the field by providing more paternity leave — which currently varies from seven days to one month, depending on the province.

“Any woman,” said Li Mingshun, “employed or not, should enjoy subsidies or allowances for giving birth, if we all recognize the social value of new lives.”

Editor: Jessica Levine.

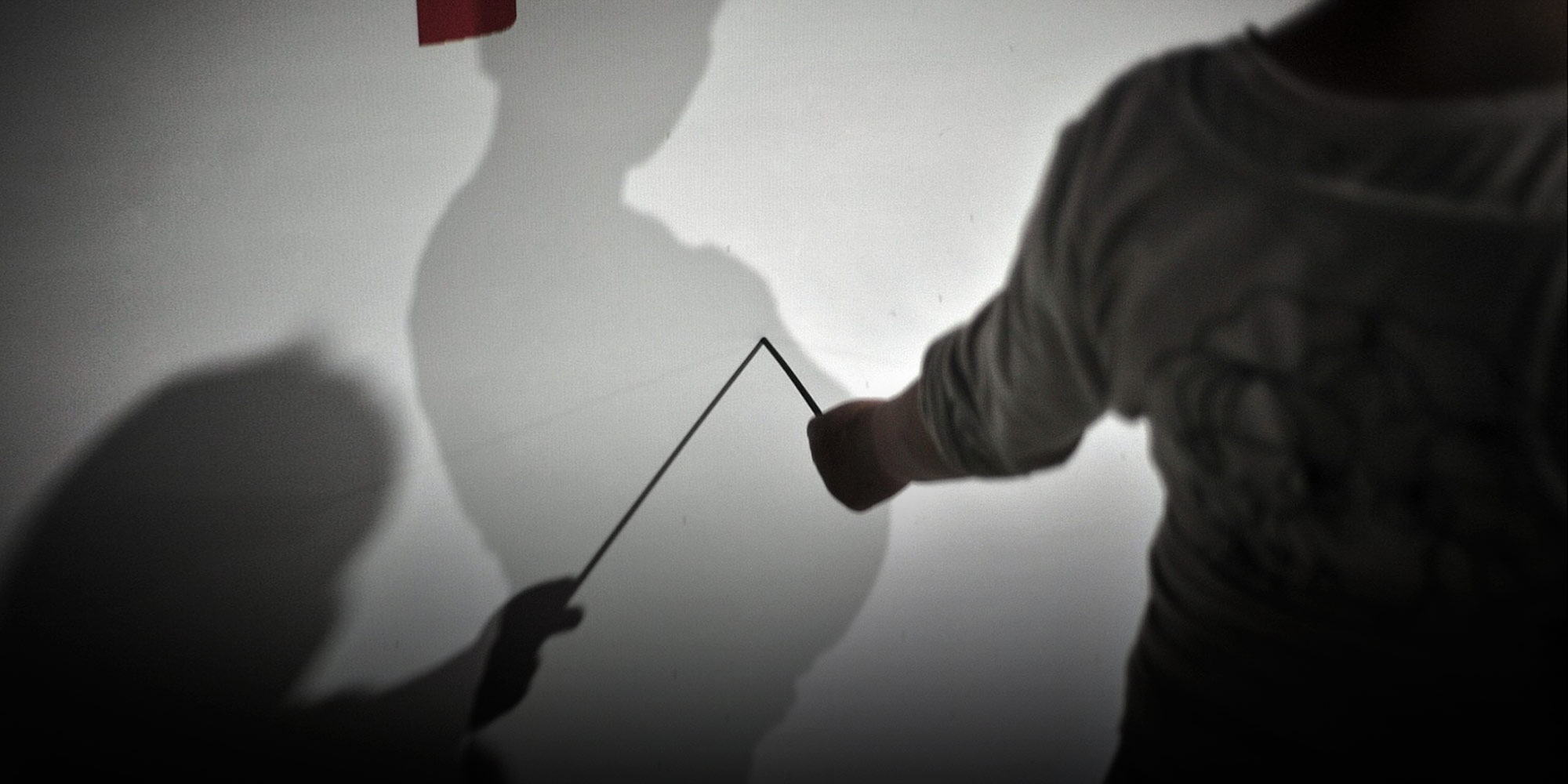

(Header image: A pregnant woman points at her shadow projected on the wall in Mianyang, Sichuan province, June 6, 2014. Liu Zheng/VCG)