China’s Drug Monopolies in Regulators’ Crosshairs

China’s top economic regulator is stepping in to ensure that people with illnesses can continue to get their hands on potentially lifesaving medications.

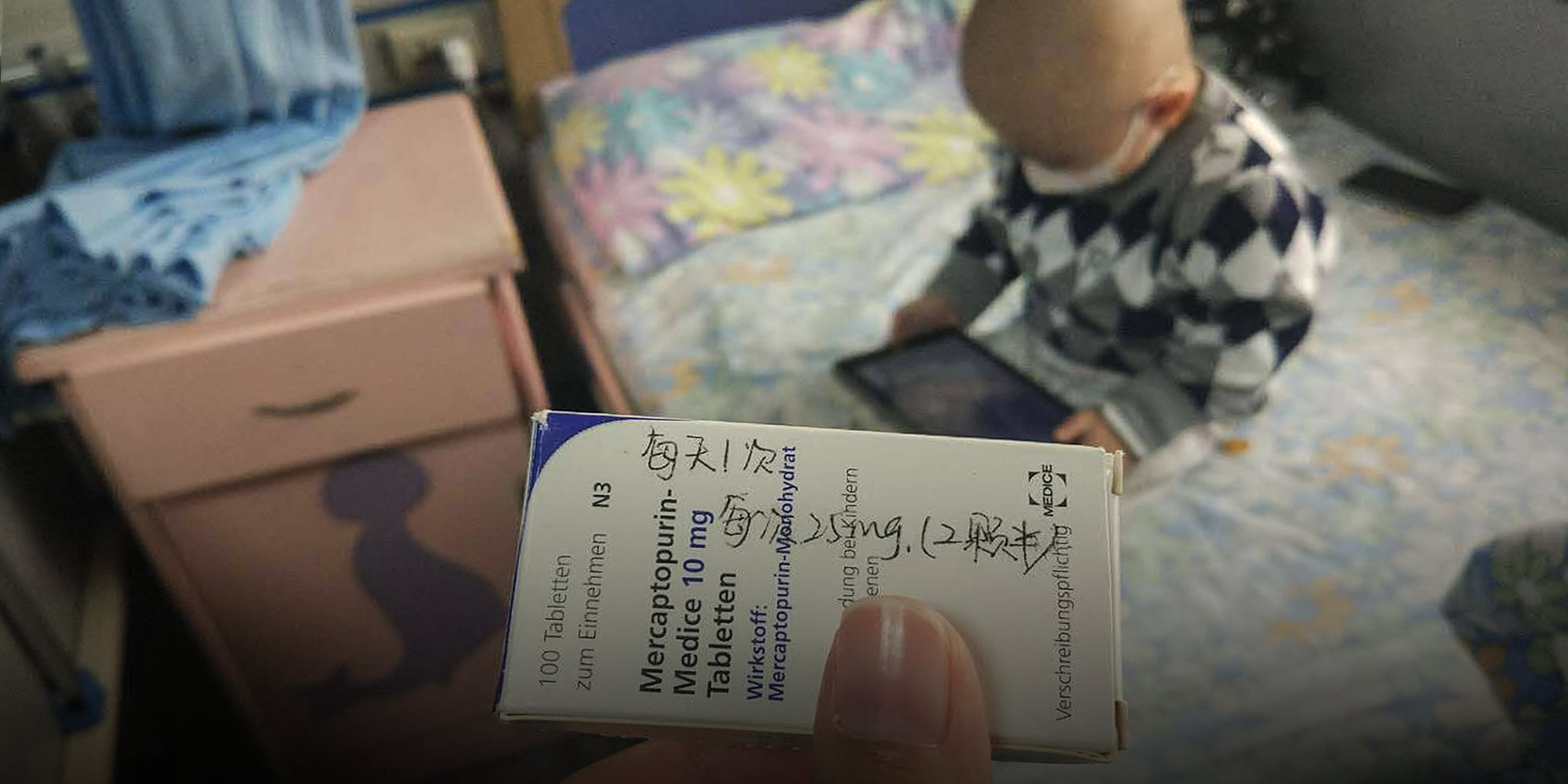

On Aug. 30, Sixth Tone reported on the critical shortage of mercaptopurine, which treats patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, the most common form of leukemia in children.

One week ago, Premier Li Keqiang urged drug manufacturers to increase their supplies of the drug. Days later, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) issued a guideline forbidding the market’s biggest players from pricing drugs too high, scooping up rare ingredients on the cheap, or attempting to influence the market in their favor.

Mercaptopurine was once widely available in Chinese hospitals, where a bottle of 100 pills could be purchased for 100 yuan ($15). But as these supplies inexplicably began to run dry at the end of 2016, bottles of 50 pills for 200 yuan — a fourfold price hike — started appearing in private pharmacies. Even those who could still afford the medicine had a hard time getting it, as its manufacturers had exclusive contracts with a handful of pharmacies in Guangdong and Anhui provinces, in southern and eastern China, respectively.

Apart from the drugs themselves, prices for rare ingredients are spiraling out of control. Last week, state broadcaster China Central Television reported on retozide, an active ingredient in tuberculosis drugs. As recently as 2014, retozide could be purchased for 150 to 200 yuan per kilogram; in August 2015, however, its price had soared to 3,800 yuan per kilogram. Monopolistic practices by pharmaceutical companies in Tianjin and Zhejiang were reportedly to blame.

Even after being fined a total of 16 million yuan over the years for restricting access to certain drugs or ingredients, some pharma companies continued to operate in a legal gray area, according to CCTV’s report.

“Some businesses had managed to control the market through underground channels,” said Xu Xinyu, chief of the NDRC’s anti-monopoly division. Xu was quoted by CCTV as saying that these companies had been unfairly selling commodities at extraordinarily high prices, or had purchased ingredients for suspiciously low prices by exerting influence over smaller, third-party suppliers.

The new guideline aims to restore a “fair market environment” by prohibiting such monopolistic behavior. The rules also stipulate that businesses cannot spread rumors, collude, hoard, profiteer, or engage in any other practice that would influence the market in their favor.

The NDRC has identified several categories of medical components that are in short supply in China, including vaccines, blood and blood products, radiopharmaceuticals, and traditional Chinese medicine ingredients.

When nine departments of the central government released a joint guideline addressing these shortages in June, Zeng Yixin, deputy head of the National Health and Family Planning Commission, revealed that of the 3,000 or so drugs approved for clinical use in China, around 130 are hard to obtain from time to time — whether due to small profit margins or stiff competition from larger manufacturers.

Editor: David Paulk.

(Header image: The mother of a boy with leukemia shows a prescription label for mercaptopurine in the pediatrics ward of a hospital in Chengdu, Sichuan province, Nov. 16, 2017. Yu Zunsu/Chengdu Business Daily/VCG)