Gay or Nay: China’s Changing Attitudes Toward Homosexuality

This is the second article in a series on gender and sexuality in China. The first article can be found here.

As a scholar of sexuality, I am often asked the same hackneyed questions: Just how many of China’s 1.3 billion people are gay? Are there more gay men or gay women in China?

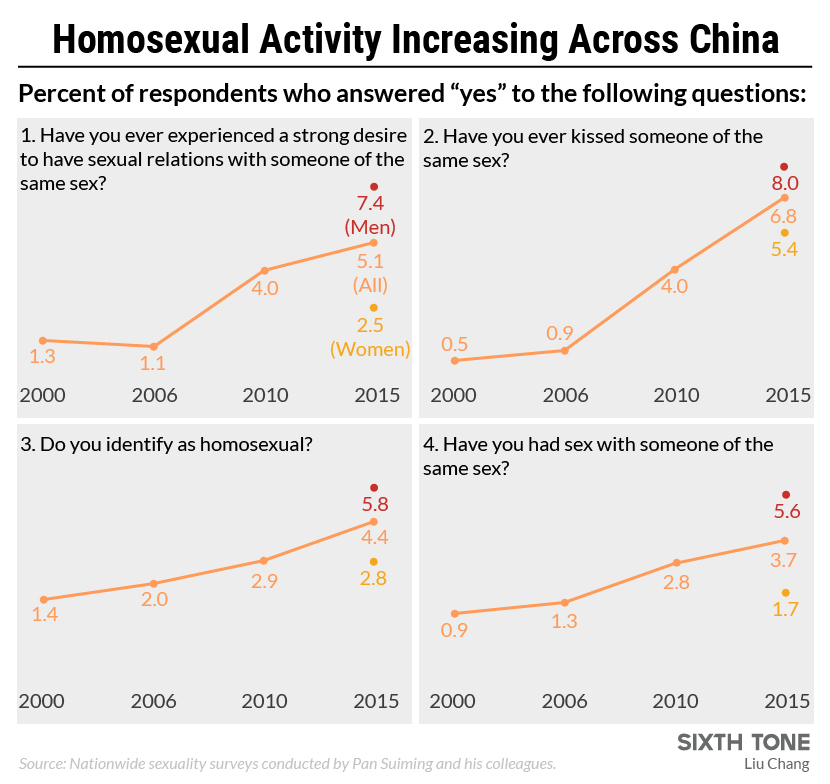

Of course, there are no concrete answers to these questions, not least because I don’t know how we should define what “gay” means. There are any number of ways to define homosexuality, and rather than going over all of them, the nationwide sexuality survey that my colleagues and I carried out four times between 2000 and 2015 asked participants four simple questions.

The first question asked if respondents had ever experienced a strong desire to have sexual relations with members of the same sex. Next, we asked if they identified as homosexual. Third, we asked if they had kissed a member of the same sex before. Lastly, we asked if they had ever engaged in sexual relations with the same sex. These questions are not perfect — there is no easy definition of what constitutes sexual intercourse, for example — but they at least elicit how respondents themselves identify their sexuality, based on personal experiences.

Our survey showed that from 2000 to 2015, the percentage of people who engaged in any kind of homosexual activity or who experienced homosexual desire greatly increased. However, do these results prove that the percentage of homosexuals in China has actually increased since 2000? Probably not.

Any statistical increase has two possible causes. The first is that the statistics reflect objective reality: Whatever is being surveyed truly has grown more common. The second possibility is that the phenomenon hasn’t really increased; it’s just that in previous surveys people didn’t dare to answer honestly.

Our surveys on homosexuality in China led us to conclude the latter. In 2000, Chinese society held much more negative views of homosexuality than today. It would have taken immense bravery, at that time, to admit that you’d had any kind of gay experience. Thankfully, it is now less and less common for gay people to face serious discrimination.

As the table shows, a significantly greater percentage of men than women responded affirmatively to each of the four questions in our 2015 survey. Studies in other nations have produced similar findings.

However, the definition of homosexuality is not limited to the scenarios outlined in our four straightforward questions. If anything, what the results of the survey tell us is that “homosexuality” is actually a blanket term encompassing a range of diverse realities.

Chinese media tends to focus more on gay men than gay women. There is a stereotype in China that gay men are all young, well-educated urbanites. This is a misunderstanding: We are used to seeing men who fit this image because they are the ones who are more likely to come out.

The fact is that men who fulfil one of the four conditions I described in the survey are spread relatively equally across all classes of society. The percentage of men who have had homosexual experiences does not significantly differ across different age groups, income brackets, or education levels — nor does it differ depending on whether subjects are from rural areas or cities, whether or not they are migrant workers, or what job they have. This might be common knowledge in most progressive, Western societies, but in China, it comes as something of a surprise.

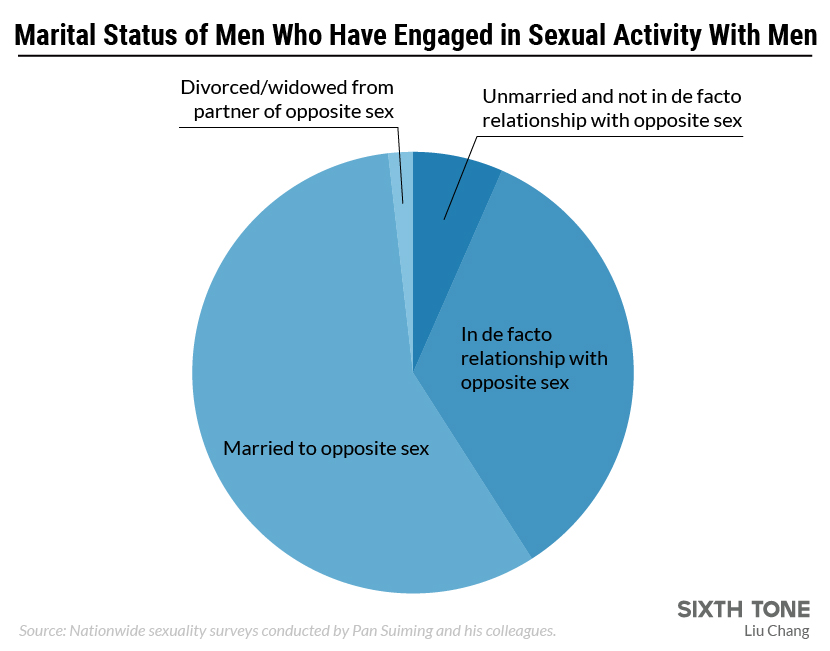

However, Chinese men who have engaged at some point in their lives in homosexual behavior differ greatly in terms of their marital status. According to the survey from 2015, the majority of these men have chosen to marry or live with someone of the opposite sex. This is perhaps indicative of the huge amount of pressure that Chinese society places on young people to start a family and carry on their genealogical line.

In recent years, as more and more Chinese people have come out as gay, homosexuality has increasingly figured into public discussion and debate, and attitudes toward it have become more tolerant. However, the most fundamental question about homosexuality in China should be: Are gay people completely equal to everyone else in terms of rights and social status? If people don’t support that principle, then any sympathy or understanding they may have for gay people means considerably less. How many Chinese people, then, support equal rights for gay people, and how many people oppose this notion?

In the three nationwide sexuality surveys we carried out between 2006 and 2015, we studied sample groups of Chinese people aged 18 to 61 years old. These groups included people of different genders, ages, and socioeconomic backgrounds. There were participants from rural areas and cities, as well as migrant workers. Participants also greatly differed in terms of profession and educational attainment. No particular demographic was overrepresented. We asked them: “Some people say that homosexuals should be completely equal to other people. What do you think?”

The graph above shows our results. The percentage of people who support equal rights for gays has remained steady, at around 45 percent over the last 10 years. Meanwhile, those who oppose gay rights have greatly decreased in number. This is not to say that a majority of people are now pro-gay rights; rather, the shift in attitudes has largely manifested as a decrease in the number of people who actively oppose equal rights for gays.

It is particularly worth noting that the percentage of people who prefer not to give an opinion has increased dramatically. This perhaps shows that some people who previously opposed gay rights have become merely indifferent; I don’t know how these people would have responded if their only choices had been “yes” or “no.” Therefore, as far as the prospect of achieving equal rights for China’s gay community in the near future is concerned, there is no cause for undue optimism — but, crucially, there are no grounds for extreme pessimism, either.

Translator: Lewis Wright; editors: Lu Hua and Matthew Walsh.

(Header image: IC)