Spilled Milk: How China Failed Its Dairy Farmers

INNER MONGOLIA, North China — Milk has ruined Cheng Guotian’s life. Once a proud herdsman, the tall, scrawny 51-year-old has had to bid the grasslands goodbye and now lives in a sterile city, where he scrapes together a meager income as a construction worker.

Fifteen years back, a government program relocated Cheng and his family from the prairie where they herded sheep, cows, and horses to a new housing development some 30 kilometers away. In the move, Cheng had to give up his freedom on the grasslands and adopt a new career: dairy farming.

The relocations in Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region were part of a government push to alleviate poverty and ease the devastating sandstorms hitting Beijing around that time — exacerbated by the dry, dusty conditions caused by grassland overgrazing. An estimated 100,000 herders in the region were compelled to relocate under the ecological migration program.

But the migration yielded another outcome: It helped boost China’s fledgling dairy industry. Data from the United States Department of Agriculture shows that in 2002, China produced 13 million tons of milk; last year, that figure had risen to over 36 million tons, ranking China third in the world for milk production after the U.S. and India.

Around 150 families from Cheng’s original village were relocated to so-called cow villages, but for many, their time there was short-lived. The 2008 tainted milk scandal — in which milk products contaminated with the industrial chemical melamine were linked to the deaths of at least six infants — was traced back to small dairy farmers, who bore the brunt of the blame. The scare triggered changes in the industry; as work dried up, some small producers were forced out of dairy farming and into the city, where they found little use for their agricultural skills.

The shift to large dairy farms following the scandal was seen as a positive step for food safety, but the dairy industry’s transformation has not been smooth — nor is it complete. The sector is still grappling with challenges on several fronts, including the high cost of producing milk in China, looming competition from imports, and wary consumers, some of whom have yet to be convinced that Chinese milk is safe.

Cheng stuck it out until 2013, when China Mengniu Dairy Co. Ltd. — one of the country’s largest dairy brands — stopped purchasing milk from individual producers in the region. Cheng sold his eight cows and followed others who had long since moved to a nearby city.

While visiting his original prairie land on a bitterly cold morning in November, Cheng reminisces about the past: the vast open spaces — his family’s nearest neighbor lived 1 kilometer away — and relaxing pace of life, with nights spent dining on freshly slaughtered sheep and swilling alcohol. His ability to kill a sheep by merely severing a main artery with his finger is of little use to him these days. “No matter how many years have passed,” Cheng says, surveying the dilapidated remains, “this is my hometown.”

China’s Milk Dream

Westerners introduced the habit of drinking milk to urban China around the end of the 19th century, but by the time the People’s Republic of China was established in 1949, the average Chinese person drank less than two glasses of milk annually. It wasn’t until the reform and opening-up period beginning in 1978 that supply and demand for the beverage got a boost. What followed was the so-called golden decade of milk in China: Beginning in the late 1990s, the country saw rapid expansion of the dairy industry and widening acceptance of dairy products among Chinese consumers.

Like many other economies of its size, China desired — and continues to desire — self-sufficiency in producing staple foods. In 2006, former Premier Wen Jiabao famously declared, “I have a dream to provide every Chinese, especially children, sufficient milk each day.” With expansive and underutilized grasslands in places like Inner Mongolia, milk seemed a good industry to focus on, and China worked to grow its dairy sector. But the nation didn’t want to replicate the dairy farming model adopted by other populous developing countries such as India, where policymakers insisted that small farms could have positive ripple effects on society. Instead, China wanted to become a superpower in milk production, using expansive American-style farms with mechanized milking processes.

But in 2008, crisis hit, giving Chinese milk producers a rude awakening and marking a turning point in the industry. In December 2007, consumers began reporting that their babies had fallen ill after drinking products from Shijiazhuang Sanlu Group Co. Ltd. — the biggest baby formula producer at the time. The following year, media exposed the scandal, and a subsequent investigation found that 41 of the 372 milk collecting stations — places where small dairy farmers pooled their milk to sell to dairy companies — that supplied Sanlu had added melamine to their product.

The nitrogen-rich industrial chemical could trick testers into thinking the milk contained higher protein levels — an important criterion among large buyers — and some collecting stations had been adding it to their milk since 2005. The melamine scandal was “the most severe systemic national food safety scandal since the founding of this country,” as Dairy Association of China Chairman Gao Hongbin said in a speech in November this year.

In total, around 300,000 babies were treated for kidney problems after drinking baby formula from Sanlu and other contaminated brands. Over 52,000 were hospitalized, and the crisis was linked to the deaths of at least six infants. Of the products tested from 109 milk powder companies, 22 companies’ goods had been contaminated with melamine, the investigation found.

The fallout was so huge that it threatened to take out one of China’s largest dairy companies. In September 2008, tests found that Mengniu’s milk powder and liquid milk contained melamine, prompting the listed company’s stock price to plummet 60 percent in one day. In 2009, a state-owned food processing company saved the dairy producer, investing 6.1 billion Hong Kong dollars ($780 million) to become its largest shareholder. Mengniu — which declined to comment for this story — had narrowly avoided total ruin.

A wave of industry consolidation followed the scandal. Sanlu was consumed by dairy company Beijing Sanyuan Foods Co. Ltd. Between 2008 and 2016, the number of dairy companies in China decreased by almost a quarter, according to data from the Dairy Association of China.

During the same period, larger farms began to dominate. While nine years ago, less than 20 percent of farms had over 100 cows, that number has now reached 53 percent, the Dairy Association’s Gao said. Chinese dairy farms with more than 1,000 cows made up just under a quarter of all dairy farms in 2015, according to the 2017 China Dairy Statistical Summary — and some of the nation’s largest farms have up to 40,000 cows. The scandal also prompted a flood of imported milk brands, with foreign companies hoping to win over consumers who no longer trusted domestic products.

For the Chinese government, the scandal constituted a major loss of face, as it revealed that the country was unable to provide safe nourishment for its own babies. Regulators moved swiftly to introduce oversight measures, some of which put pressure on smaller players. Immediately following the scandal, China set a safety limit for melamine — low levels of the chemical are sometimes found in milk due to the plastic packaging. In June 2009, China rolled out its first-ever food safety law, which made adding unauthorized chemicals to food illegal. And in 2013, authorities announced regulations requiring baby formula producers to use milk sources that they controlled. Massive dairy farms, which were easier to regulate, became the most desirable model.

The government’s efforts to develop the milk industry — first relocating herdsmen to cow villages, and later promoting consolidation among dairy companies — have divided experts. Although Lei Yongjun, chairman of Beijing-based consulting firm Proper Tao and a longtime dairy industry watcher, backs both moves, he thinks the government should have offered greater aid to herders when the market shifted against them. He points out that one benefit of big farms is that they are more likely to receive the support of local governments and investors. “You have to have capital to raise cows,” Lei says. “If we didn’t have the 10,000-cow farms, we wouldn’t be able to support giant companies like Mengniu and Yili.”

But Ian Lahiffe, a former agribusiness consultant and current China country head for Allflex — a manufacturer of monitoring equipment for dairy farms — says that while megafarms may make sense if they are near big cities like Shanghai, they should generally be discouraged. “The ‘bigger is better’ race to grow comes with huge growing pains,” he says, citing pollution and difficulties in controlling the spread of disease as examples.

Last Farmer Standing

At 5:30 a.m. on a snowy November morning in the Inner Mongolian village of Duhumu, 58-year-old Liang Yu, who is Han Chinese, and his ethnic Mongolian wife Naranchimeg rise from their heated brick bed to milk their cows.

It’s pitch-black as they shuffle to their cowshed, just meters from their small redbrick bungalow. Liang leads the cows one by one into the cowshed — which is lit by a single naked bulb — to be milked. Naranchimeg, whose chubby, tanned face and wide smile betray her 56 years, carefully measures out the animals’ morning feed and dishes it into a dented metal bucket.

The couple are among a dying breed of small-time dairy farmers: They have only seven cows, four of which currently produce milk. Back inside the house, Naranchimeg weighs the collected milk on an electronic scale under the watchful gaze of a portrait of Genghis Khan — the founder of the Mongol Empire — that hangs on the wall. Today’s yield is disappointing: just 45 kilograms. “We didn’t get much milk,” she says in a deflated tone. In the mid-afternoon, the cows will be milked again; Naranchimeg hopes they’ll be able to produce another 30 kilograms.

These days, Liang can expect to sell the milk for 4.6 yuan ($0.70) per kilogram to his two chief customers, both of which are specialty dairy shops in a nearby town. That brings in around 300 yuan per day, or roughly 10,000 yuan a month — but after the costs of feed and grass are subtracted, the couple are left with a monthly income of slightly more than 1,000 yuan. Yet as Naranchimeg explains, the pair have few other options. “I’m too uneducated to do anything else,” she says with a laugh.

The couple wed in 1985, when interethnic marriages were slowly gaining wider acceptance. In 1999, Liang lost his job as a grain seller along with millions of others following a severe financial crisis in the state’s cooperative grain-selling system. In 2003, the couple switched industries and resettled under the push to promote cattle farming, which authorities described as “a project to enrich the people.” The government helped cover the cost of purchasing cows and supplied the couple with a house worth 10,000 yuan.

But the melamine scandal dealt the pair a serious blow. Liang recalls hearing that the local milk collecting station added what he terms “fat oil” and mixed it with water to make the milk thicker. Looking back today, he says the substance in question was most likely melamine.

Now, Liang and Naranchimeg are among a dozen people still living in the desolate village, with many former residents having either moved to cities or returned to the prairie. During Sixth Tone’s recent visit, the only other sign of life was a pair of stray dogs rummaging for food scraps around rust-eaten vans abandoned in the snow.

Winning Back Trust

Convincing consumers to drink more milk could be the key to the industry’s future. On a per capita basis, dairy consumption in China is low, even when compared with the country’s Asian neighbors South Korea and Japan. The vast majority of Chinese are lactose intolerant, which market research firm Mintel describes as “one of the main barriers” preventing the industry from reaching its full potential. A lack of consumer understanding of milk’s nutritional value is another, the report adds.

While cultural and physiological issues persist, allaying consumer concerns will remain a central challenge. Near Shijiazhuang — a city in northern China’s Hebei province more commonly associated with chronic pollution problems than clean dairy — lies Junlebao Dairy Industrial Tourism Park. The sprawling collection of fields and buildings was opened in 2012 by Shijiazhuang Junlebao Dairy Co. Ltd., one of the country’s biggest milk companies, to teach Chinese consumers about milk. The attractions — marked with bilingual English and Chinese signage — show visitors how cows are milked and fed, and there’s also a museum devoted to dairy science. “[The park] is the world for cows. It is also the paradise for cows,” one sign reads in English.

Claire Lee, a 25-year-old tour guide at the park, says it’s important to rebuild consumers’ trust following the 2008 scandal. “People can come here to see what they drink every day, and they will have faith again,” she says.

The site was awarded the second-highest grade in the national tourism administration’s ranking system for attractions, and it has drawn around 500,000 people over the past two years — but it’s also a working farm with 4,500 cows. During a recent visit by Sixth Tone, visitors ranged from families with small children to a 30-strong delegation of People’s Liberation Army soldiers.

In the visitor center, which sells cuddly cow toys and yogurt drinks, 32-year-old local Wang Cuijuan, a kindergarten teacher, is taking a break after visiting the park with her husband, infant son, and a friend who works for Junlebao. When her son turns 2 in four months, he’ll switch from his infant baby formula — an American brand that Wang buys from Hong Kong — to a formula for toddlers. Wang has already decided on Junlebao. “In recent years, mothers are no longer that crazy about foreign brands — they place more trust in domestic brands,” she says.

Gao from the Dairy Association said at a recent industry forum that the market share of domestic milk powder brands dropped from 65 percent to 30 percent in the wake of the melamine scandal, but has now bounced back. He estimated that domestic brands could even make up 70 percent of market share this year. “Dairy in China has entered a new stage,” he said, pointing to the industry’s more ambitious goals and higher level of quality.

But Lahiffe, the former agribusiness consultant, says China’s dairy industry will have to change tack if it is to thrive. “It’s got to be less about volume and more about premium [quality products],” he says. The infrastructure used to deliver cold, fresh milk is still underdeveloped in China, though it is improving. New distribution possibilities — such as e-commerce — could make it easier to provide fresh milk, according to Lahiffe. “The chance to get good-quality milk to homes in China is going to increase,” he says.

Meanwhile, imports, which currently make up 13 percent of milk sales, continue to pose a threat to the domestic market. Chinese consumers look favorably upon foreign liquid milk brands, including ultra-high-temperature products — milk that’s been processed to ensure a much longer shelf life than fresh milk — from countries such as Germany and New Zealand. Imports grew 38 percent last year from the year before, down from the 44 percent year-on-year growth in 2015, according to Mintel.

Lahiffe points to the high costs associated with milk production as a major challenge for the Chinese dairy industry. “Margins are very tight,” he says, estimating that the cost of producing a liter of milk in China is roughly twice that of Ireland, his native country. Factors include rising salaries and the high price of cattle feed in China.

The years of strain have taken a serious toll on some major market players: Earlier this year, northeastern China’s largest dairy producer, China Huishan Dairy Holdings Co. Ltd., announced it was 26.7 billion yuan in debt. It has since begun preparations for liquidation.

The same financial pressures may have contributed to the melamine crisis, according to Xun Lili, a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences who has studied ecological migration in Inner Mongolia. In her research, Xun wrote that pressure on small-time farmers to produce milk cheaply was to blame for the scandal — not a moral failure on the farmers’ part. The cow villages were little more than an inexpensive source of milk for dairy companies, she explained.

Greener Pastures?

Milk giants have already wiped out most small players — and midsize farmers could be next.

In Yirilejihu, another cow village in Inner Mongolia, 45-year-old Bat — an ethnic Mongolian who owns 300 cows — has witnessed the industry’s shifts over the years and has had to fight to stay afloat.

Like Cheng and Liang, Bat and his family lived on the prairie for generations until 2003, when they were relocated to a cow village 35 kilometers away. As a village leader, Bat was tasked with persuading fellow villagers to move. The herdsmen’s original houses on the prairie and the fences between their land allotments were torn down; in their new home, they live side by side in neat rows of bungalows.

“I didn’t have a choice — that was the policy,” Bat says from his living room, where a cross-stitched poem by Mao Zedong hangs on the wall.

In 2011, the government began compensating herders from eight provinces and autonomous regions — including Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, and Tibet — for the loss of their grasslands. In 2016, for example, this meant that each person in Bat’s village received 5,000 yuan from the government.

Bat built his own milk collecting station in 2008 — the year of the melamine scandal. In the aftermath, it took a full year for him secure the authorizations to supply milk to Mengniu.

A decade ago, when milk supply was tight, Bat recalls sales representatives from Mengniu and Inner Mongolia Yili Industrial Group Co. Ltd. fighting to buy milk from his farm. Once, a representative from Mengniu blocked a truckload of milk that was being taken from his farm by Yili, prompting a call to police. Yili also declined to comment for this story.

But in recent years, Bat says Mengniu has become increasingly demanding. “They have too many requests,” he explains, adding that he suspects it’s all part of a deliberate and surreptitious strategy to get rid of medium-sized producers like him.

“Mengniu is a national project, and the government supports it,” says Bat. “If they [Mengniu] said they didn’t want milk from ordinary people, they wouldn’t be able to justify it, and the country wouldn’t give them preferential policies anymore.”

Tired of the constant pressure from Mengniu, Bat no longer supplies milk to the company. Two years ago, he began selling at lower prices to a new buyer: Xibei, a restaurant chain from Inner Mongolia. He’s begun pivoting from milk to cheese and has scored 1.3 million yuan in government subsidies for a new 900-square-meter dairy processing factory, making his farm one of only two in the county to receive such a handout.

“If you don’t have your own brand and don’t make any noise, then you’ll just be in survival mode forever,” Bat says. “If you go and give it a try, there might be a way out.”

Contributions: Chen Na, Qian Zhecheng, and Cai Yiwen; editor: Julia Hollingsworth.

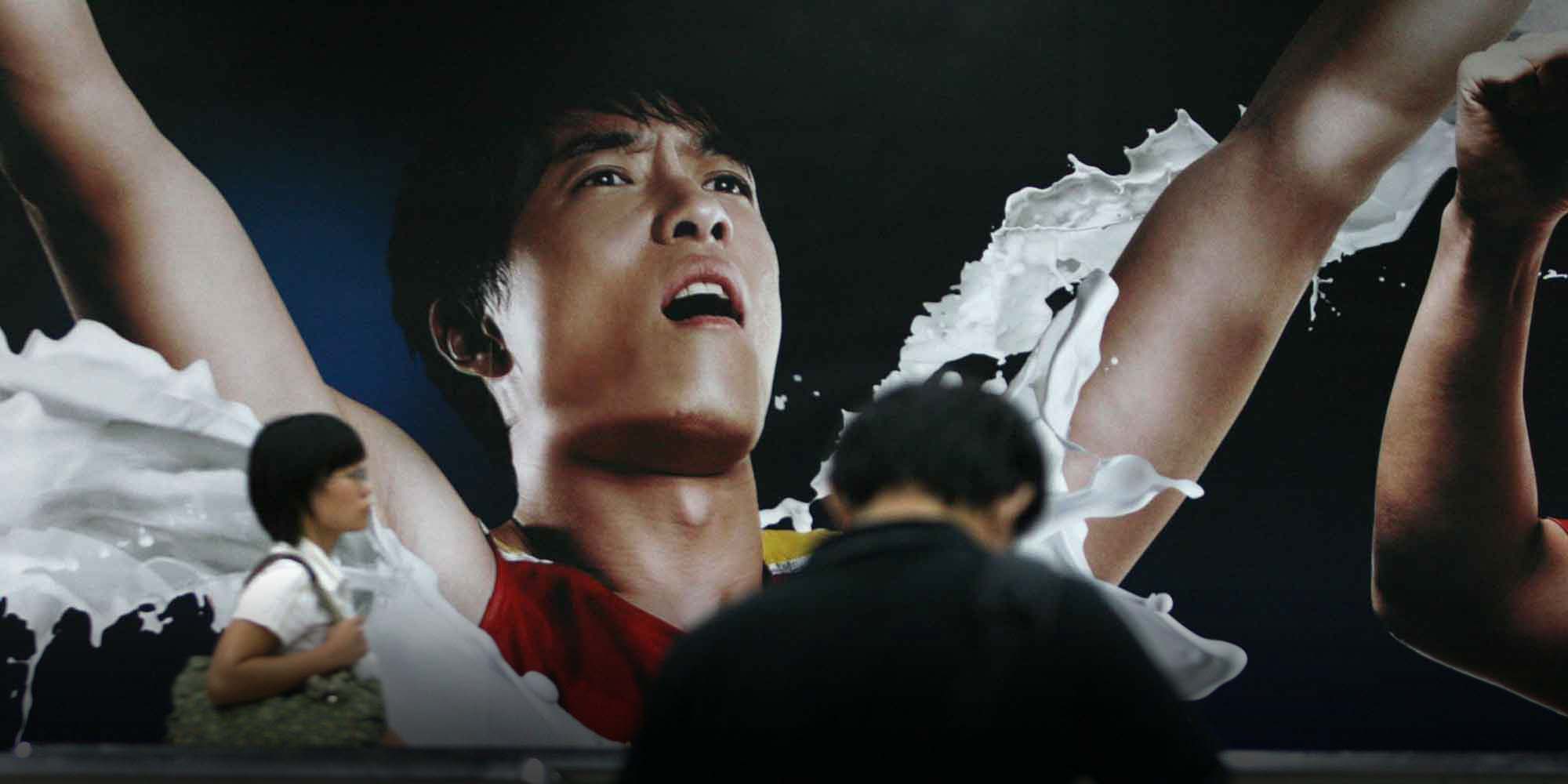

(Header image: A 2008 ad for Yili features Liu Xiang, China’s first Olympic gold medalist in men’s track and field. Yili used Olympic athletes in promotional material during the Beijing Olympics. IC)