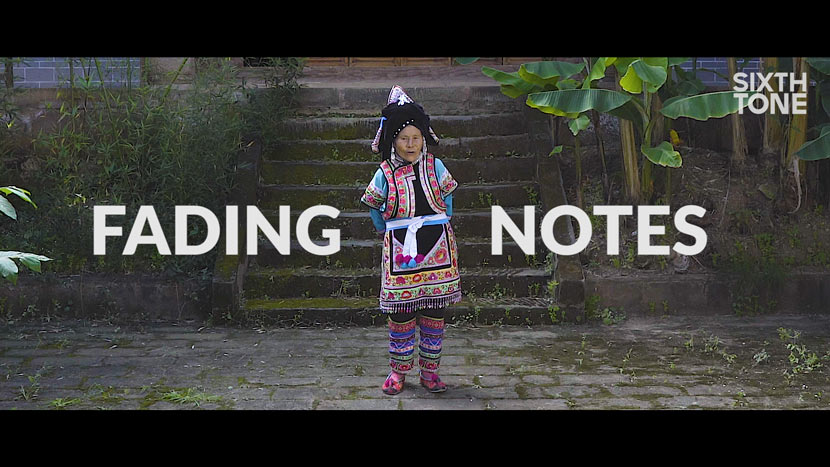

Fading Notes: The Slow Demise of Yunnan’s Epic Songs

YUNNAN, Southwest China — Guo Youzhen takes a deep breath and starts singing about the origins of the universe.

She sings of Gezi, the Creator, who forged the earth and the sky from nothing. She sings of Ah Fu, whose three sons clung fast to the edge of the sky and hauled it downward to meet the earth below. She sings of the pythons that encircled the earth and divided it into uplands and lowlands, the ants that nibbled at the ground’s frayed edges until they all lay straight, and the menagerie of wild animals that applied the finishing touches.

Three pairs of boars, three pairs of elephants,

dug the soil for 77 days and nights.

They made the mountains; they made the hills.

They made the flats, and the beds that water fills.

Guo reaches the end of the verse and pauses for breath. “It’s a very long song,” she smiles. “You could sing for three days and nights, and still not reach the end.”

Big sky, small world — this is right.

Heaven and earth are well-aligned.

There are only a handful of people left who can sing the creation myths of the Yi people, one of China’s 55 official ethnic minorities, from start to finish. The myths form the centerpiece of meige, a style of sung storytelling that has been passed down among Yunnan province’s Yi communities for centuries.

Today, meige is under threat. Most master singers are middle-aged or elderly. Younger generations of Yi have adopted new ways of life, working in faraway factories instead of the fields back home, and fewer people have time to devote to the art. “Reform and opening-up has brought severe, unavoidable challenges for meige,” says Yang Fuwang, an expert on ethnic minority cultures at Chuxiong Normal University in Yunnan. “The unique environment in which it was passed down no longer exists.”

Meige is one of many oral storytelling and singing traditions in societies across the world. They are windows into the immense breadth of human experience, especially in cultures whose languages historically had no written forms, or whose people are largely unable to read and write.

Across China’s southwestern regions, where people of the dominant Han ethnicity have mingled with a panoply of ethnic minorities for centuries, folk singers often return to tunes, themes, and motifs resembling meige. Up in the northeast, the Manchu traditionally perform ulabun, singing about a great heavenly war, the origins of the region’s ethnic groups, and the biographies of revered shamans. Out near the country’s western border, the Kirgiz people perform the “Epic of Manas,” a 500,000-line poem detailing the exploits of a 17th-century war hero in his battles against the marauding peoples of Central Asia.

However, the vast majority of the world’s oral cultures now exist on the margins of mainstream society. Once incorporated into larger political states, these communities struggled to sustain their folk traditions amid the hegemonic onslaught of official languages, written texts, and education systems that value empirical approaches to history over mythological narratives.

The Yi mainly reside in four of China’s southern and southwestern areas: Yunnan, Sichuan, and Guizhou provinces, and the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. Small numbers of Yi also live in Thailand and Vietnam. Though the Chinese state classifies the Yi as an ethnic minority, this all-encompassing moniker belies the confounding diversity of this 9 million-strong group. Yi people may identify as one of 80 or so subgroups and speak any of the region’s family of Loloish languages that have more in common with Burmese than Mandarin. They may practice Buddhism, shamanism, or — in areas that hosted late 19th-century European missionaries — Christianity.

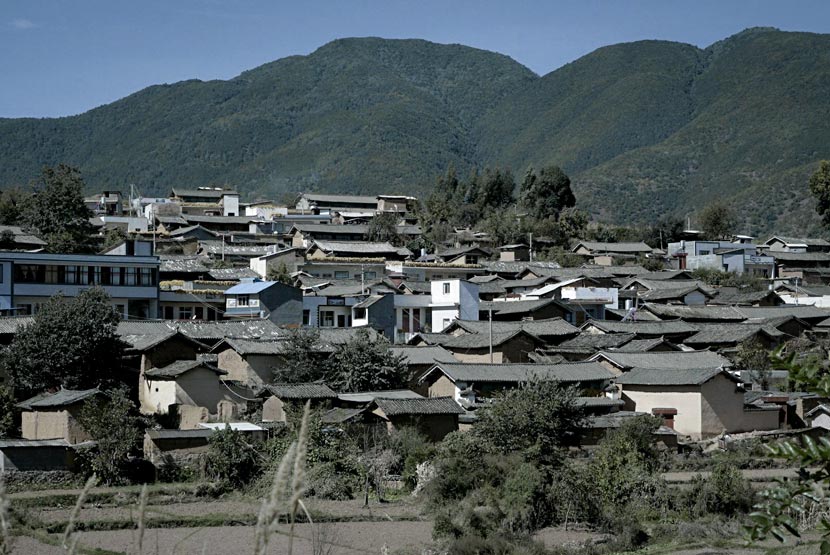

Not all Yi sing meige; the songs are the preserve of cultures native to the Chuxiong Yi Autonomous Prefecture in central Yunnan. The songs are as varied as the Yi themselves — meige singers in one village may color their versions with slightly different lyrics and inflections from those in the next valley. But one village in particular positions itself as meige’s ancestral home: Mayou, located about a four-hour drive northwest of provincial capital Kunming. A single road tethers the village to the town of Yao’an, snaking through hilly terrain past a great azure reservoir.

From June to September, Mayou’s rice paddies flush verdant as heavy rains swell the brook that splits the village in two. But during Sixth Tone’s visit in mid-November, the days sit dry and cool, the brook has dwindled to a lazy trickle, and the fields have turned a subdued blend of ocher, shorn short during the recent harvest. Courtyards, balconies, and rooftops are festooned with ears of sun-dried corn waiting to be fed to the local livestock.

Village officials estimate that more than 95 percent of Mayou’s residents are Yi. Guo was born here in 1943, the youngest of four children. Now a spry 74-year-old with an easy smile, only her posture — she stoops slightly to the right — betrays a lifetime spent tilling the fields. She remembers childhood days helping her parents farm, which gave way to evenings when the whole family would retire to the hills above the village, light bonfires, prepare meals of buckwheat noodles and wild herbs, chat with other villagers, and sing meige songs.

“When we were young, the whole family would sit beside the fire, listening to Grandma and Grandpa sing. That was how they passed it on: I listened, and little by little, I mastered it myself,” says Guo through an interpreter, who puts her remarks into Mandarin. Nobody in Mayou can read or write Yi, and — like all the meige singers interviewed for this piece — Guo requested that Sixth Tone use her Chinese name.

Yi people in Mayou historically learned folk songs by word of mouth. Whereas the creation myth was typically only sung at marriages, funerals, and major festivals, communal singing of more casual ditties enlivened the everyday drudgery and connected younger generations to a swath of shared history. “My mother and my older sister could both sing very well,” says Guo. “We sang wherever we went, whenever we walked or took the train anywhere. When it rained, we’d sing about the rain; when the sun shone, we’d sing about that, too … For us, meige was something you sang all day, every day. You’d sing about whatever you saw.”

Guo Youzhen sings ‘meige’

Today you are offered wine and meat

so that you will guard the fortunes of the whole family

and shall protect the peace of the whole village.

Thus, when family members take journeys,

things will go smoothly in all directions.

After the Communists won the civil war in 1949, Guo, then 9 years old, attended school for the first time; she dropped out at the age of 15 to come back and work in the fields. By that point, she had already been singing meige for a couple years, and her precocious talent caught the eye of a drama troupe from a nearby city, who offered to train her as an actor. “But my parents weren’t particularly worldly,” she says. “[They said that] if I went, they’d miss me and worry too much, so they didn’t let me go.”

During the early years of the revolution, the new Communist state sent ethnographers to some of the nation’s farthest-flung corners to survey and report back on its non-Han peoples. Their work informed the 1954 establishment of the minzu shibie, a vast classification project that resulted in the formal recognition of an initial 39 ethnic groups, including the Yi, in the national census. Also during this period, meige songs were recorded, transcribed, translated, and published for the first time.

Yet early state-sponsored ethnic scholarship was often carried out by overzealous cadres who dogmatically applied Marxist theories of social progress to wildly divergent minority groups. The central government cast many minority practices as feudal relics and often sought heavy-handed means of “socializing” Yi people who performed meige songs. “[Scholars] have sometimes edited them, sometimes taken things out for political correctness,” says Mark Bender, an expert on southwestern China’s oral literatures and a professor of Chinese culture at Ohio State University. “A lot of that was done in the 1950s. More recent versions tend to be more accurate; they are not edited as much as in the past.”

During the Cultural Revolution of the late 1960s, officials periodically banned meige performances, and singers omitted or adapted politically incorrect lyrics — or set songs about Mao Zedong to existing meige tunes. Despite this, Guo still taught the songs to her own children. In the 1980s, as the state became more tolerant toward ethnic minority culture, she helped rejuvenate Mayou’s singing traditions: “I wanted to teach, and went into [local] schools,” she says. “[Students] came to learn if they wanted to, but if they didn’t want to, I didn’t force them.”

Today, meige is recognized as a form of national intangible cultural heritage. The Mayou village government receives funding from the local branch of the publicity department and the tourism bureau, with the goal of preserving the tradition. Singers are loosely classified into prefectural-level, county-level, provincial-level, and national-level “inheritors” of the tradition, depending on how many songs they have mastered and how many students they can teach. A Chuxiong prefectural government webpage listed 258 registered meige inheritors in 2014, five of whom were national-level singers. Guo’s name appeared at the top of the list.

Yet Yang, the ethnic minorities expert at Chuxiong Normal University, takes a dim view of the existing cultural heritage protection system, claiming that the officials who created it were invited to Mayou from other parts of the country and did not consult with the local Yi. “How is it scientific if you don’t ask the local ethnic minority community to help make the plan?” he asks.

Guo rarely teaches nowadays, on account of her old age. Luo Ying, Guo’s great-niece and a provincial-level meige singer, has taken up the mantle. Every Thursday afternoon, 49-year-old Luo teaches snippets of meige songs to a classroom of 30 or so students at Mayou’s primary school.

In addition to creation myths, meige includes many other songs marking different stages in life, such as the so-called baby meige, a selection of lullabies that mothers sing to their newborns. Luo’s rendition of baby meige tunes is strikingly different from Guo’s creation myth: Where the latter is full-throated and exultant, Luo’s song is subdued and soothing — her voice sometimes fading to a cooing whisper and her lips barely moving.

Luo Ying performs baby ‘meige’

Spring is here; spring is here!

In spring we must sow the fields.

In spring we must weave cloth.

Then everyone has clothes to wear,

and everyone has food to eat!

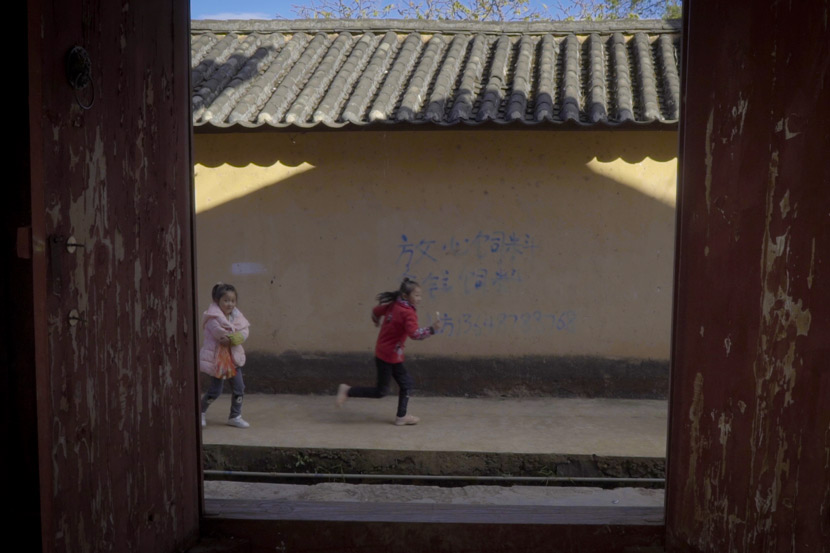

In the playground outside the school building, girls dance in neat rows to schmaltzy recordings of Yi music, while boys blow piercingly into traditional gourd flutes. All are clad in traditional garb usually reserved for festivals: black jerkins and trousers for the boys, and black jerkins with white trousers for girls.

On the surface, Luo’s class seems to recreate the word-of-mouth environment in which meige was historically passed down: She sings a line of verse, and her pupils obediently holler it back. Additionally, both the school board and the local education bureau sponsor cultural events that showcase the songs. All this gives Luo confidence about the songs’ future: “I do worry that meige will die out, but the government is paying more and more attention to it these days,” she says, “so I’m still hopeful.”

Yet Luo admits that it’s difficult to envision large numbers of youngsters practicing their skills beyond primary school. After all, singing meige songs around the fire isn’t the only form of entertainment anymore. “Kids today all listen to pop songs,” Luo sighs. “Previously, our generation didn’t sing pop music. We just learned meige every day and listened to our elders singing by the bonfires at night. We had more time to study it.”

“When children sing meige today, their songs don’t have the same flavor,” says Guo, the elder singer. “They go to study at school and have to learn Chinese, not Yi. So when they sing, it doesn’t sound as good as it did in the past.”

Yang is skeptical of the school’s meige classes. “What [children] learn at school is just the baby meige,” he says, explaining that these songs contain little of the historical origins of the local Yi. Certain other classroom songs, he adds, come from standardized written texts that bear little resemblance to their original versions.

Meige evolved in a more sedentary society than today’s, back when the Yi depended more heavily on their land for sustenance and income, and close-knit kinship bonds ensured that songs and performance styles passed largely intact to successive generations. Local shaman-priests known as bimo, who were masters of Yi language and scriptures, helped to ensure meige’s preservation. No bimo have lived in Mayou for half a century, though a few remain in Dayao County to the north.

Today, the ties binding local people to the land are breaking. Most of Mayou’s working-age population has migrated to China’s eastern cities in search of jobs. The children they leave behind usually live at school or with elderly grandparents, and finish their education in Yao’an or other nearby cities. The immense burden of homework and exam preparation leaves little time for singing meige.

In the past, once a local woman reached the age of 18, it was customary for her family to build a small hut in their courtyard for their adult daughters to live in. A stout wooden hut still stands in Luo’s backyard, surrounded by dried chili leaves that crunch underfoot. These days, it is a storehouse for farm tools and other bric-a-brac; when she was younger, though, she slept in the hut, and her husband-to-be came by in the evenings to serenade her from the courtyard. He’d sing “youngster’s meige,” a collection of verses that a lovelorn young man would use to entreat a woman to come meet with him.

I went and stood behind your home.

In back was a flowering peach tree.

You were sitting at your loom,

your face prettier than a pear bloom,

looking nicer than a peach blossom.

If the woman was interested, she would respond with verses of her own.

Ah, now I know!

So it was you, hiding out front,

peeping at me!

So it was you, hiding out back,

peeping at me!

But you never had the guts to face me!

All that attention nearly scared me stiff!

Over the last 70 years or so, Chinese scholars have collected hundreds of meige songs, recording the tunes and writing down lyrics to preserve them for posterity. Yet the very act of committing songs to writing changes how audiences interact with them. “In a live performance, you’ve got a person there. You can hear the song; you can see their movements. It goes into your ear that one time,” says oral literature expert Bender. “Oral tradition is always just a version. There’s no set text; every time these things are performed, there is a continual recasting of the tradition.”

Written texts have a tendency to codify the information they record, attaining higher status compared with oral variants. Transcriptions of meige become a master text, “and what is sometimes overlooked is that this is just one particular version,” Bender explains.

Meige has been published in Yi, but there is a catch: The official Yi script approximates a dialect spoken in neighboring Sichuan province, nearly 400 kilometers to the north. Those communities do not perform meige and speak a form of Yi markedly different from that of the Mayou villagers, whose dialect has no written form of its own.

Teaching meige to schoolchildren and collecting songs both help to ensure that the tradition doesn’t die out, but they also raise deeper concerns about the form in which it will be preserved. With the art form ill-suited to modern lifestyles, will Mayou’s next generation of performers sing with the consummate grace of Guo and Luo, or will they be left with only a partial version of meige songs, melodies, and styles?

Such disruption is a typical effect of social change brought about by modernization, according to Bender. “These traditional cultures are the things that get compromised, because people have other interests, other priorities, other technologies,” he says. “People have to prioritize their lives.”

Last year when the flowers bloomed,

Sister asked me for a date.

This year as the flowers scent,

Brother comes here searching,

Ga-la-mo-po.

Brother is a honeybee.

He comes circling around.

Only when a sweet flower’s plucked

will his heart settle down,

Ga-la-mo-po.

Luo Wenhui is a hard man to pin down. Mayou’s rakish, chain-smoking village committee head hurries from one engagement to the next, meeting with officials, visiting residents, cutting off conversations to answer a barrage of phone calls. He’s as busy as you might expect for someone tasked with overseeing Mayou’s economic transformation.

Whether it’s possible to address development issues while preserving Mayou’s unique cultural heritage, chiefly meige, depends on how you judge the success of both modernization and cultural preservation. Either way, Luo Wenhui has his work cut out for him. The bare facts are these: Mayou is poor; until recently, its children lacked access to high-quality education; and its infrastructure lags behind that of Yunnan’s more prosperous areas.

The national government has an ambitious plan to eradicate poverty for all citizens by 2020. For grassroots cadres like Luo Wenhui, that means finding out what every family earns and reporting it to higher-level officials. It’s onerous work.

Born in 1971 in a neighboring village, Luo Wenhui dropped out of primary school in third grade and went to work in the fields. He began learning meige at the age of 9; his mother, popular among the village women, was often invited up to the hillsides in the evenings. The young Wenhui would tag along, listening to the songs of his elders, watching the fires slowly burn out, and imbibing the heady fragrance of the surrounding sandalwood trees.

“All of Yao’an County is going to be pulled out of poverty this year,” says Luo Wenhui when Sixth Tone finally corners him in the smoke-filled village committee common room. “We’re just about to host people from the Poverty Alleviation Office, so we can’t afford to take any weekends off.”

Provincial authorities have each decided on a poverty line and tasked front-line officials with raising local incomes above it. In Mayou, the line is set at 3,200 yuan ($485) in annual household income — a difficult target for grassroots cadres to reach. “Poverty relief out here is done on a one-to-one basis,” Luo Wenhui explains. He must accompany cadres on time-consuming house calls to investigate the circumstances of each family, including how much money they earned in the past year.

Much of life in Mayou still revolves around agriculture. During the planting and harvesting seasons — from April to June and September to November, respectively — villagers busy themselves with growing and selling rice, vegetables, and tobacco smoked with gusto by men of the region. In the off-season, the village government channels funds into a cultural protection drive: Some 25 young meige enthusiasts gather in the village committee’s meeting room and study the songs with the aid of a local inheritor.

Luo Wenhui himself is a prefectural-level inheritor of the tradition. Every year, he teaches at least two meige students in a quiet corner of the committee office. “But my students all practice in their spare time,” he says. “The last couple of days, for example, they’ve basically been too busy in the fields [to practice singing]. Sometimes they leave the village to find work, and sometimes they’re at home, so it’s not a fixed arrangement.”

Even with the help of state subsidies and community projects, Luo Wenhui is not optimistic about how long they can sustain the meige tradition. “We won’t be able to pass it on by relying solely on a few inheritors or a bit of funding from the propaganda and culture departments,” he says. “If we want a long-term solution, then we need big investment in ecotourism based around our ethnic culture.”

Luo Wenhui sings ‘meige’

This is the custom of the village.

Whether herding livestock on the mountains

or working in the lowlands,

we need your protection.

The stones are many on Tanhua Mountain;

as you stand upon the rocks, guarding over us,

let us labor in peace.

Let us herd our stock untroubled.

Luo Wenhui cites two local ethnic minority prefectures as inspiration for Mayou’s pivot toward tourism: Honghe, with its spectacular rice paddies, and Diqing, home to the picturesque ethnic Tibetan town of Shangri-La. Yet perhaps a better point of reference would be Shilin, a county near Kunming famous for its vertiginous karst formations. There, the Sani people — a subgroup of the Yi — have performed their own oral epic for centuries. Known as “Ashima,” the poem was made into a famous film during the 1960s, and to this day locals invoke its romantic narrative to promote all sorts of tourist attractions. While “Ashima” performers are also dwindling in number, the song stands as an example of how impoverished minority communities can monetize their oral traditions.

Bender wonders to what extent Mayou could emulate Shilin’s success — as there is only room for so many tourist sites drawing on local lore. “This is one of these fantasies that sometimes get put into reality … I would have my doubts about how successful that would really be, but I’d support their efforts if they moved on it,” he says. Yang is less equivocal: “It’s not likely to happen,” he says, adding that a plan to transform Mayou into a tourist hot spot surfaced seven or eight years ago, but would have cost several hundred million yuan and never got off the ground. “The plan was basically out of touch with reality,” Yang says.

Mayou’s folk singers are the custodians of a rich and well-loved, but ultimately fragile, tradition. While locals have a genuine interest in maintaining it, meige songs — so cumbersomely lengthy and difficult to master — often demand that budding performers sacrifice other things that give modern life dignity: making money in the city, putting their children through school, watching TV shows on a smartphone.

In a village playing economic catch-up with the rest of the province, the clash between tradition and modernity is hard to miss. On a wall behind the village committee parking lot, a red-and-white Party proclamation blares: “National Unity Is a Wonderful Pact! The Harmonious Meige Is Boundlessly Charming!” Painted beneath it is an ad for a domestic internet provider: “Get the Whole Family Onto China Mobile, and Enjoy Free Broadband for All!”

Over in the village’s culture center, elderly meige singer Guo comes to the end of another verse and smiles. “When I was young, I could sing like this all day,” she says, shuffling over to rest awhile under the gently swaying bamboo and Japanese banana trees. “But now, I’m too old and get tired too easily.”

Additional reporting: Liang Chenyu; editor: Kevin Schoenmakers. Song lyrics courtesy of Mark Bender and Dong Jiacheng.

(Header image: Luo Ying poses for a photo in Mayou Village, Yao’an County, Yunnan province, Nov. 17, 2017. Daniel Holmes/Sixth Tone)