The Young Workers Facing an AI Threat

This article is part of a series that explores how artificial intelligence could change life in China.

Zhang Yawen only launched her career two years ago, but she believes her days as an accountant are already numbered.

After completing her degree in accounting from Southeast University in Nanjing, the capital of eastern China’s Jiangsu province, the 24-year-old scored a job verifying financial statements at a local branch of a state-owned company.

But Zhang thinks her work involves very little skill. “All you need to do is to sit in front of a computer and then click, click, click,” she says bitterly. “It won’t take long for a machine to replace me.”

Zhang has reason to be concerned: Artificial intelligence (AI) software is gradually snatching jobs from human accountants in China. Although the software hasn’t been rolled out at her company yet, businesses like global auditing firm PricewaterhouseCoopers are providing their clients with AI-powered software that can automate simple accounting tasks and do them faster and better than humans. A similar impending AI takeover is occurring in the customer service industry, according to Yuan Hui, the founder and chairman of Shanghai-based chatbot company Xiaoi, which counts some of the country’s biggest commercial banks as its clients.

Concerns about the human cost of AI development are playing out in industries across China. AI is expected to boost the nation’s economic growth rate by 1.6 percentage points in the next two decades; at the same time, automation and AI could force around 13 percent of China’s projected 757 million-strong workforce to change jobs by 2030, according to a December report by global consultancy McKinsey & Company. Jobs that involve routine activities and predictable, programmable tasks — like accounting and retail — will go first. But in the long term, the jobs that could be affected by AI run the gamut from drivers to lawyers.

“The effects of AI on China’s workforce will be sweeping,” says Deng Zhidong, a professor at Tsinghua University’s department of computer science and technology. “It’s going to be a process: First, supplement; then, optimize; and then finally, replace.” And if the government doesn’t move to help workers develop new skills and invest in AI education for children, there might be mass unemployment in the future, cautions Tu Yongqian, a researcher at the National Academy of Development and Strategy at Renmin University of China.

For millennials just entering the workforce, the prospect of competition from both top graduates and AI technology can be anxiety-inducing. A Gallup study in the United States found that 37 percent of millennials — aged 21 to 37 — were in danger of being replaced by AI at work. This demographic was more likely to be in lower-level positions that could be filled by the new technology, compared with 32 percent for older generations.

Although not all Chinese millennials Sixth Tone spoke to were concerned about job prospects, Jonathan Woetzel, a senior partner at McKinsey, says they should be worried. As millennials would make up the largest portion of the workforce in China in the next decade, they would feel the greatest impact from an AI takeover, he says. “Everybody, including millennials, has to change what they do, as individual activities are increasingly done by machines,” Woetzel says.

Only a semester into his law degree at a U.S. university, one 23-year-old student from Beijing is unnerved — not by his workload, but by his job prospects back in China, where courts and law firms are increasingly using AI to find past cases to cite as precedent and write legal documents. “In 10 years, the entire law industry will probably be gone,” said the student, who asked not to be named out of concern for his career. “Lawyers only know the law and how to analyze it and write documents — all this can be done by computers.” He says he’s already planning to pivot toward consulting because he sees law as a “dead-end path.”

However, China’s job prospects might not be all doom and gloom. Although 13 percent of the country’s workforce may need to switch jobs, the proportion is much higher for advanced economies: Up to one-third of workers in the United States and Germany and nearly half in Japan, where the cost of labor is higher than in China, will be affected by AI or other forms of automation, the McKinsey report found.

And China is no stranger to massive social transformation. “Relatively speaking, China has done something this big already,” McKinsey partner Woetzel says, referring to China’s rapid shift from a largely agrarian society to an industrial powerhouse over the past half century. “If China makes new investments to effectively and continually retrain and re-employ workers, then its transitional problem will be more restrained,” he adds.

While jobs involving routine, standardized tasks will no longer be available to humans, there is likely to be an increase in jobs that only a human can do, says Mark Purdy, managing director and chief economist at Accenture Research, the research arm of management consulting firm Accenture. Purdy, who has recently done research on Chinese productivity, says jobs requiring high degrees of creativity, empathy, and social interaction will stay, while other opportunities — such as jobs in AI-related sectors — will spring up.

Unlike the U.S.-based law student, Wang Jinxing, a litigation lawyer in the eastern city of Hangzhou, is unfazed at the possibility of being replaced by a robot. Machines will only be able to take over the legal field if they can understand moral principles and emotions, says the 28-year-old. Wang points to the example of a human judge’s ability to respond differently to situations that seem the same in principle, like a driver running a red light because they’re drunk, compared with someone else running a red light to save people. “Unless AI itself masters laws and operates according to a certain level of moral standards — which shouldn’t be above or below the average level of the society — it will be really hard for AI to judge a case,” he says.

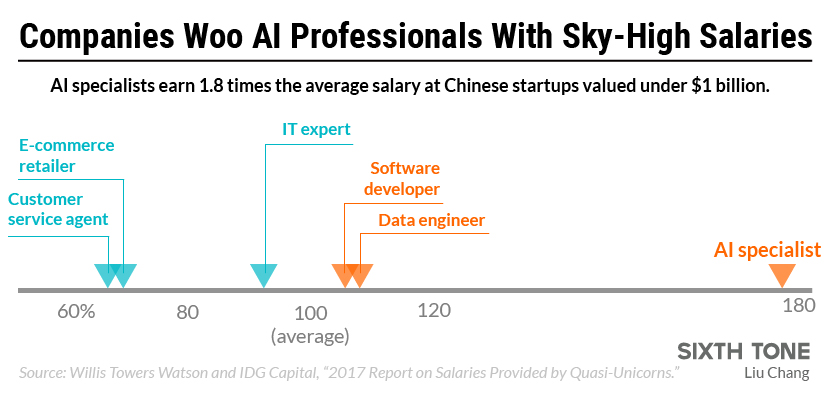

And while some young people are panicking about losing out to AI, the technology has generated a host of new occupations. In Xi’erqi, Beijing’s tech hub, AI specialists receive sky-high salaries, prompting the techies to joke that they’ve driven up housing prices in the northwestern suburb. The AI talent shortage — and China’s ambition to lead the global industry — has prompted Chinese tech companies to dole out lucrative salaries and bonuses to attract top AI specialists from around the world. Fresh graduates in AI-related majors can earn up to 300,000 yuan ($46,000) in their first year of work, compared with 120,000 yuan for the average Ph.D. graduate.

One recent tech graduate is Gao Pengfei, a 25-year-old from eastern China’s Shandong province, who decided to study to become a machine-learning engineer after realizing it was one of the best-paid jobs. Now with a master’s degree in data science from the University of Southampton in the U.K., he uses AI to assess borrowers’ credit risks for a microlending company in Beijing. Although the hours are long, the high salary and sense of fulfillment lead him to believe he made the right choice.

Of course, not everyone can be an AI expert, but gaining a solid foundation in science, technology, engineering, and math skills is a good start, says Accenture’s Purdy. He wants to see China’s education system put greater emphasis on creativity and adaptability to better equip workers for the future. For people in sectors or regions where there’s likely to be a lot of AI-related disruption, the government may need to implement more targeted transition plans, such as retraining initiatives.

Tu, the researcher at Renmin University, thinks the government should upgrade its social security system to better protect workers. He also says businesses should shoulder some of the responsibility to retrain employees.

But Xiaoi’s Yuan, who has a staff of around 500 people, advises workers to think about what they can do to stay competitive — such as upgrading skills or retraining — and then take the initiative to do so themselves. AI has prompted both fear and anticipation in China, he says, as it could both take away jobs and make lives better.

“Whether people like it or not, AI development is an irreversible trend,” Yuan says, invoking a biblical metaphor: “Eve has taken a bite of the apple.”

Correction: A previous version of this article stated that AI and automation could force 757 million Chinese to change jobs by 2030. The total projected workforce in 2030 is 757 million, and 13 percent of workers could be forced to change jobs.

Editor: Julia Hollingsworth.

(Header image: Zhang Zeqin for Sixth Tone)