No More Storks: The Apps Delivering Babies to Chinese Women

For 27-year-old Sunny Wang, getting pregnant has been a roller coaster.

After three months of trying for a baby, Wang — who lives in eastern China’s Shandong province — was diagnosed with endometriosis, a condition that can cause infertility.

“I couldn’t believe this had happened to me — I’m still so young,” says Wang, who married her longtime boyfriend in October, the same month her doctor told her she had endometriosis. “I love kids. If my husband and I didn’t wait so long to get married, we’d probably already have some.”

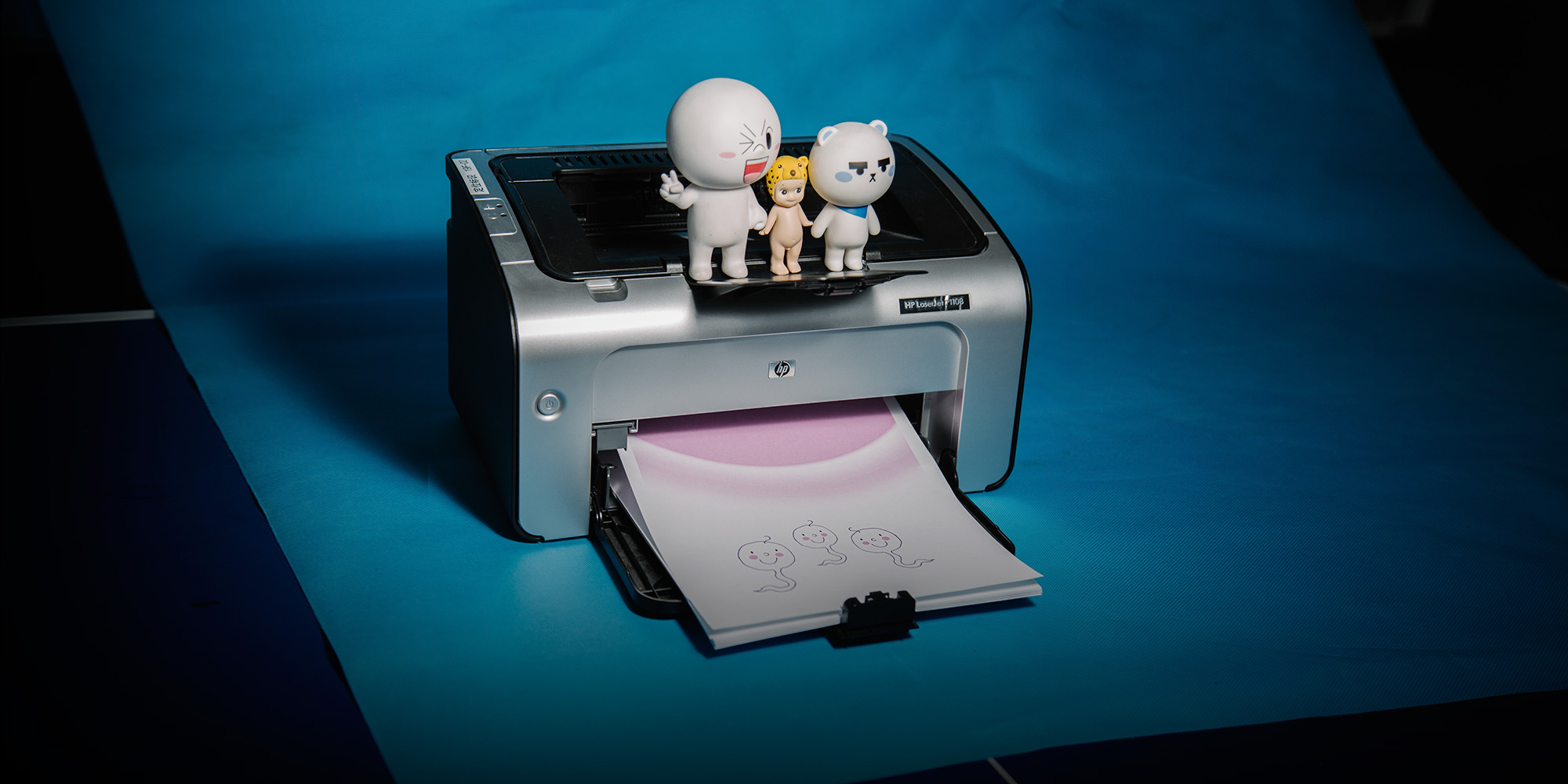

Desperate to conceive, Wang turned to the internet for help. A flashy pink app featuring a sperm icon caught her eye. The popular app — called “Fengkuang Zaoren,” which roughly translates as “Crazy for Making Babies” — boasts an estimated 11 million users and allows women to keep a daily log of their reproductive cycles, share pregnancy advice with other users, and read curated fertility articles.

Wang is among a growing number of Chinese women eschewing traditional fertility wisdom passed down through generations in favor of modern technology. Experts expect China’s booming fertility market — including in vitro fertilization clinics, nutritional supplements, apps, and wearables that measure women’s body temperature to predict when they’re most fertile — to continue growing. In the next few years, the industry could be worth nearly 100 billion yuan ($15 billion), says Wang Yin, founder of digital fertility monitor company Shecare.

“Around the world, there has been a trend of people tracking their physiological conditions, such as footsteps, heartbeats, and sleep,” Wang Yin, who is not related to Sunny Wang, tells Sixth Tone. “Data collected by these apps can help users better understand themselves.”

While similar pregnancy apps, like popular cycle-tracking apps Glow and Clue, are widely used in the West, fertility technology is expected to take off in China as more couples try for a second baby after the one-child policy was scrapped two years ago, adds Wang Yin.

There’s also a growing number of Chinese women struggling with fertility, as more couples get married and have children later. Only 26 percent of people got married before the age of 24 in 2015, down from 47 percent in 2005, according to data from the Ministry of Civil Affairs. The latest data available from the China Population Association — a research group supervised by the National Health and Family Planning Commission — showed that the nation’s infertility rate rose from 3 percent in 1992 to 12.5 percent in 2012.

Infertility — a diagnosis that applies to a couple who doesn’t fall pregnant after a year of trying — is on the rise due to stress and women giving birth later, says Huang Sen, founder and CEO of Haoyunbang, an app that answers pregnancy questions and helps people connect with fertility clinics. But even for those who don’t meet the definition of infertility, trying to conceive a child can be an anxiety-inducing ordeal. “They will start wondering if there is anything wrong with their bodies if they don’t get pregnant within six months,” Huang tells Sixth Tone, adding that female fertility starts to decline at age 27 and drops “dramatically” after 35.

Chen Rudai, who lives in the southwestern metropolis of Chongqing, may only be 23 years old, but she’s already thinking about her fertility. Although she and her husband just started trying for a baby, she has already downloaded two apps to track her period, body temperature, and ovulation. “We haven’t told our parents yet that we’re trying to get pregnant,” Chen says, adding that her parents will probably start to meddle and impose their own ideas about ways to improve fertility once they find out.

Many young women like Chen are actively using technology to get pregnant, rather than relying on advice from their mothers as previous generations have done, says Wang Yaotang, president of Qingdao Yuren Hospital in Shandong and of no relation to Wang Yin or Sunny Wang.

“Back [when I was growing up], there was a mindset that there wasn’t much science involved in the process of getting pregnant,” the 52-year-old gynecologist, who has worked in the industry for 28 years, tells Sixth Tone. Couples were more likely to worry over whether a woman could give birth to a boy, rather than if they could get pregnant at all, he adds. “Things have changed now,” says Wang Yaotang. “People, especially young people, are using their phones to track their health conditions so they can conceive in a more efficient and scientific way.”

Behind this trend is a shift in what Chinese people consider a trusted information source, says Dai Wangyun, a Ph.D. student at East China Normal University in Shanghai who studies folk health beliefs. For centuries, knowledge about pregnancy was controlled by the matriarch of the family and passed down from generation to generation by word of mouth. Traditional Chinese fertility advice included consuming dried dates and hot water with brown sugar for women, and chowing down on oysters for men. Eating meat was seen as conducive to conceiving; well-known Taiwanese actress Barbie Hsu, a longtime vegetarian, was famously persuaded by her mother-in-law to eat meat to help with her fertility. Others believed that changing the feng shui of their bedroom, including removing sharp objects like knives, could improve their luck.

Things started to change in the 1980s, when the government implemented the one-child policy and sent representatives around the country to promote sexual health education, especially contraception. “These three forces are vying for the attention of wannabe-parents,” Dai tells Sixth Tone, referring to traditional pregnancy beliefs, state sex education, and the rise of new information online. “It’s up to the couples to decide which source they want to listen to.”

For health professionals, the data generated by fertility apps — which some users opt to share with their doctor — is both a blessing and a gamble. Hospital president Wang Yaotang praises the apps for helping obstetricians identify patterns in lifestyle and health factors that could affect fertility. But he also warns that couples can’t rely solely on apps to get pregnant, as there are many factors that affect fertility.

Tian Jishun, medical director for medical search engine Dingxiang Doctor and a former obstetrician, is even more dubious about the self-monitoring technology. Not only is there no evidence that fertility apps can improve a user’s ability to get pregnant, but the data collected might not even be reliable, he argues. For instance, body temperatures need to be taken first thing in the morning, something Tian believes the average app user might struggle to do correctly.

“If anything, logging one’s health statistics every day will only remind a woman that she’s not pregnant and increase her anxiety,” says Tian. “That’s the last thing a couple want when they’re trying for a baby.”

But for Sunny Wang, the technology seemed to work just fine. In October, Wang began uploading the results of her daily urine test strips to Fengkuang Zaoren, allowing the app to pinpoint when she was most fertile.

A mere two months later, she was pregnant. And while it’s not clear whether the app contributed to her conception success, Wang thinks it deserves some credit.

Editor: Julia Hollingsworth.

(Header image: Wu Huiyuan/Sixth Tone)