Student Rankings Are Making Parents and Kids More Miserable

Last month, Chinese online news outlet Tencent published a provocative blog in which a parent claimed that they would rather their child be at the bottom of their class and happy than top of their class and miserable. Though the benefits of this approach may seem self-evident to those brought up in more holistic education systems, it nonetheless incited vociferous debate among China’s young parents.

The author of the piece, who wrote under the pseudonym Ai Chuan, described himself as a member of the precarious middle-class: He owns his own home, has his own car, and works a respectable job. However, he and his wife had both been raised in the Chinese countryside and put in years of hard work in order to afford their current urban lifestyles. Their mortgage repayments are high, city life is exorbitantly expensive, and they know that their quality of life will plunge dramatically if the economy tanks and brings their salaries down with it.

The writer also worried about the education of his son, who is currently in fourth grade and therefore around 10 or 11 years old. When he was born, the blogger wrote, he only wanted him “to grow up happy and healthy.” In kindergarten, he never sent his son to any kind of cram school. But at elementary school, as other parents sent their children to at least three or four extracurricular classes per week, the writer eventually followed suit and signed his son up to supplementary classes in calligraphy, English, reading, writing, and the International Mathematical Olympiad.

Over time, the writer continued, he and his wife went from largely disregarding their son’s academic achievement to closely watching his place in the class rankings. Teachers in China grade students based on intellectual achievement, and publish these scores so that parents and students know how the child is doing compared to others in their peer group. Among students and on social media, those at the top of the class are known as xueba, or “study emperors,” while those with the lowest scores are pejoratively called xuezha, or “study dregs.” In a country where exams can decisively affect your future, xuezha are often mocked by their fellow students for their poor scores.

The writer went on to describe how the anxiety that his son would become a xuezha affected his mood. One day, he wrote, he flew into a rage at his son for no good reason. Afterwards, he and his wife realized that what they assumed was natural concern about their child’s academic achievements was actually fear of the negative stigma surrounding xuezha. The blogger resolved to mend his ways and raise his son to value kindness and happiness over academic achievement: “So what if others see him as only a xuezha?”

I’ve worked as a Chinese language teacher and class administrator at an elementary school in Ningbo, a city in eastern China’s Zhejiang province, for almost 15 years. My daughter is currently in the third grade at a different school. When I think back to how I treated her during her earliest years at school, I empathize with how the abovementioned blogger felt. I would worry inordinately about even the most mundane of school tests; I’d feel depressed and angry if her name didn’t appear at the top of the list in, say, a Chinese vocabulary quiz.

I was always a good student, even though the term xueba didn’t exist when I was at school. I believe that I have taught my daughter effective methods to achieve academic success. I understand many of the principles underlying early-childhood education, and have read widely on how children develop and the best ways to interact with them.

But my daughter is still not a xueba. And though I no longer care that she isn’t top of her class, I used to worry about it a lot.

Children in China have it so hard because most people strongly associate the concept of jingying — the social elite — with good performances at school and college. Millions of parents buy into the snobbery and discrimination that perpetuates the myth of the jingying, believing that only elites get respectable jobs, health insurance, and a stable life.

I realize that much of my own frustration with my daughter’s grades comes from my complicity in jingying culture. Fortunately, as a teacher, I understand that the jingying myth is mostly bogus. I’ve taught very bright pupils who have gone on to lead mediocre lives and less academically inclined students who went on to achieve great things. Academic prowess is important and exam success opens a lot of doors in China, but it is not the be-all and end-all.

There is a deep-seated cultural problem with classifying students along the axis of xueba and xuezha. A truly civilized society is one that enables individuals to find their place within it and respects them on their own terms: Sure, it would be great to be elite, but at the same time, it doesn’t matter too much if you’re not. Everyone deserves to pursue their own goals and to be treated with respect; but at the moment, our obsession with exam grades is breeding a generation of anxious, hyper-competitive parents and stressed-out students.

The fight to become a xueba makes many Chinese parents risk-averse when it comes to their children’s upbringing. But here, “risky behavior” can be as simple as allowing young children time to play and learn outside the confines of school or extracurricular classes. In 2016, of the 180 million children at elementary and high schools around the country, 138 million of them took at least one extracurricular class. Given that academic snobbery pervades even preschool education, why would any well-meaning parent go against the grain? After all, the logic goes, if your kid doesn’t get into a good kindergarten, then they won’t get into a good elementary school, middle school, or university. Then they won’t find a good job, won’t earn a high salary, and won’t enjoy the middle-class lifestyle their parents worked so hard for.

Fear of becoming a xuezha gives rise to a culture of fear that must be overhauled if we are to recover the purpose of education. Going to school is, of course, a legal requirement, but it is also a way of experiencing the complexity of society, interacting with people from diverse backgrounds, and developing into a well-rounded person. Being a xueba does not necessarily mean that you will be any better at these things.

The cultural shift we need does not require China’s notoriously hands-on parents to completely divest control over their children’s lives. Instead, they should withdraw partially and understand that while the role of parents is to shape their children’s characters, in the end, they cannot fully control how they end up. When I was growing up in the 1980s, my generation took on an enormous burden of schoolwork, too. Today, a growing number of us are parents and hope that our kids will grow up in a more holistic environment than we did.

This attitude has fueled the so-called happy education movement, which favors more holistic educational models and often emulates the more relaxed learning styles and moderate amount of homework of Western school systems. But this movement, in turn, is being compromised by deep social currents that privilege educational attainment above all else and compel parents to fill their kids’ free time with burdensome extracurricular activities. This isn’t holistic, and it doesn’t make kids happy.

A truly happy education places just enough pressure on children for them to understand the value of intellectual pursuits and a strong work ethic, but does not stop them from enjoying all kinds of learning opportunities, especially the unstructured learning that takes place when people are left to their own devices.

And that is why Ai Chuan’s article not as liberating as it seems. By telling his son that it’s fine to be a xuezha, he is allowing the kid to “own” his lack of academic prowess. But on a deeper level, he accepts the legitimacy of a system that pits the pursuit of happiness against academic success. This is equally unhealthy for his child, and doesn’t solve the problem.

The words xueba and xuezha first appeared as internet buzzwords, but have now slipped into common parlance. While they were originally used as humorous ways to express scholastic aptitude, their usage is highly problematic. As a teacher, I know the importance of validating the talents of every student, whether that means congratulating them on good exam scores, sporting ability, artistic talent, or emotional intelligence. Similarly, it is essential to criticize students who fall short of expectations and spur them on to greater achievements. However, the above terms further strengthen a twisted view of the value of education, one in which “clever,” “intelligent” xueba are the only archetype of success, and the achievements of the less academically inclined are pushed out of the mainstream.

Translator: Owen Churchill; editors: Zhang Bo and Matthew Walsh.

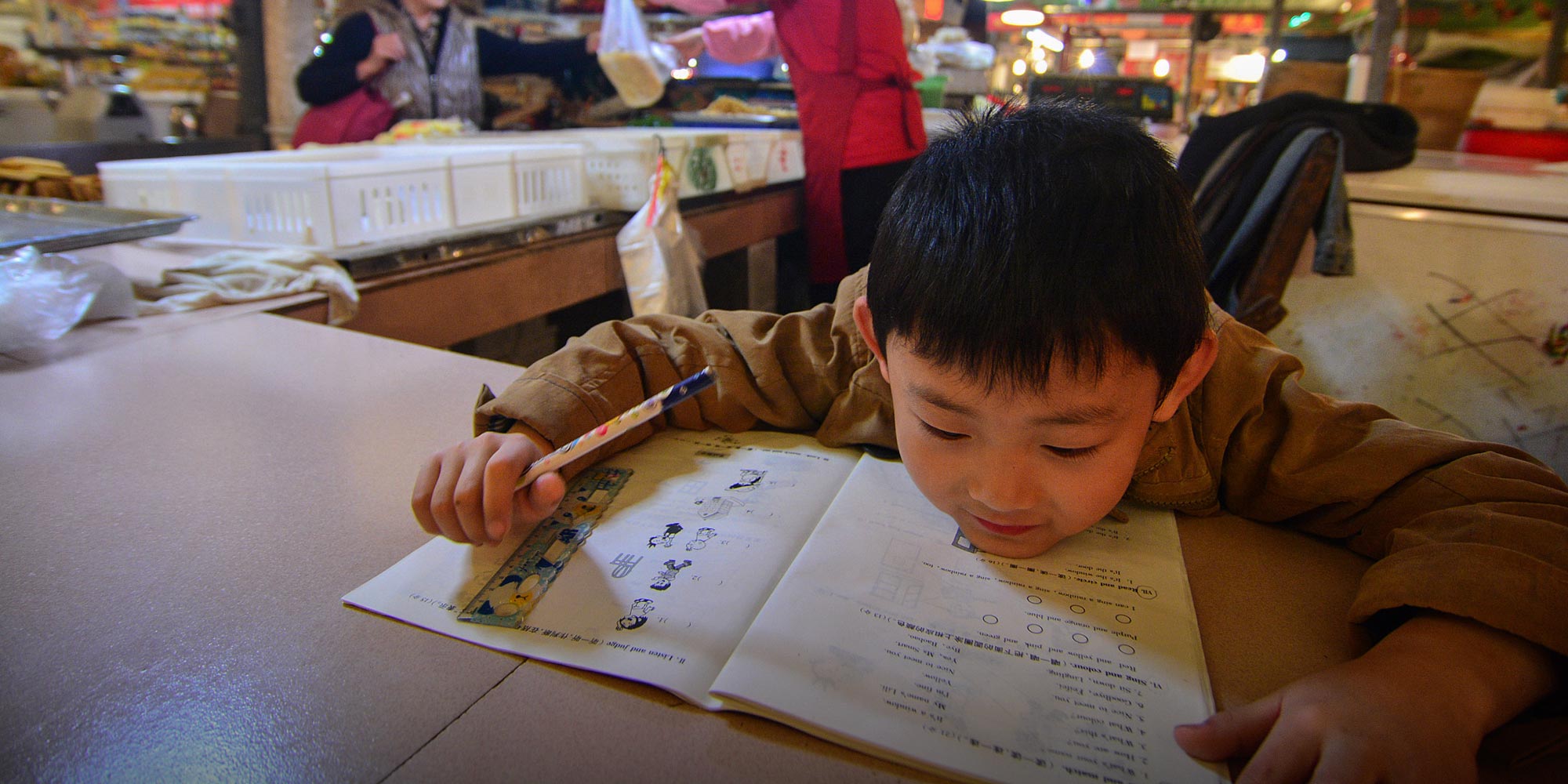

(Header image: A boy works on a homework assignment in Qingdao, Shandong province, Nov. 6, 2013. Zhou Kun/VCG)