Remembering China’s Silver-Screen ‘Butterfly’

To mark the 110th birthday of China’s first “queen of the movies,” 200 portraits are being displayed at the Shanghai Center of Photography (SCoP).

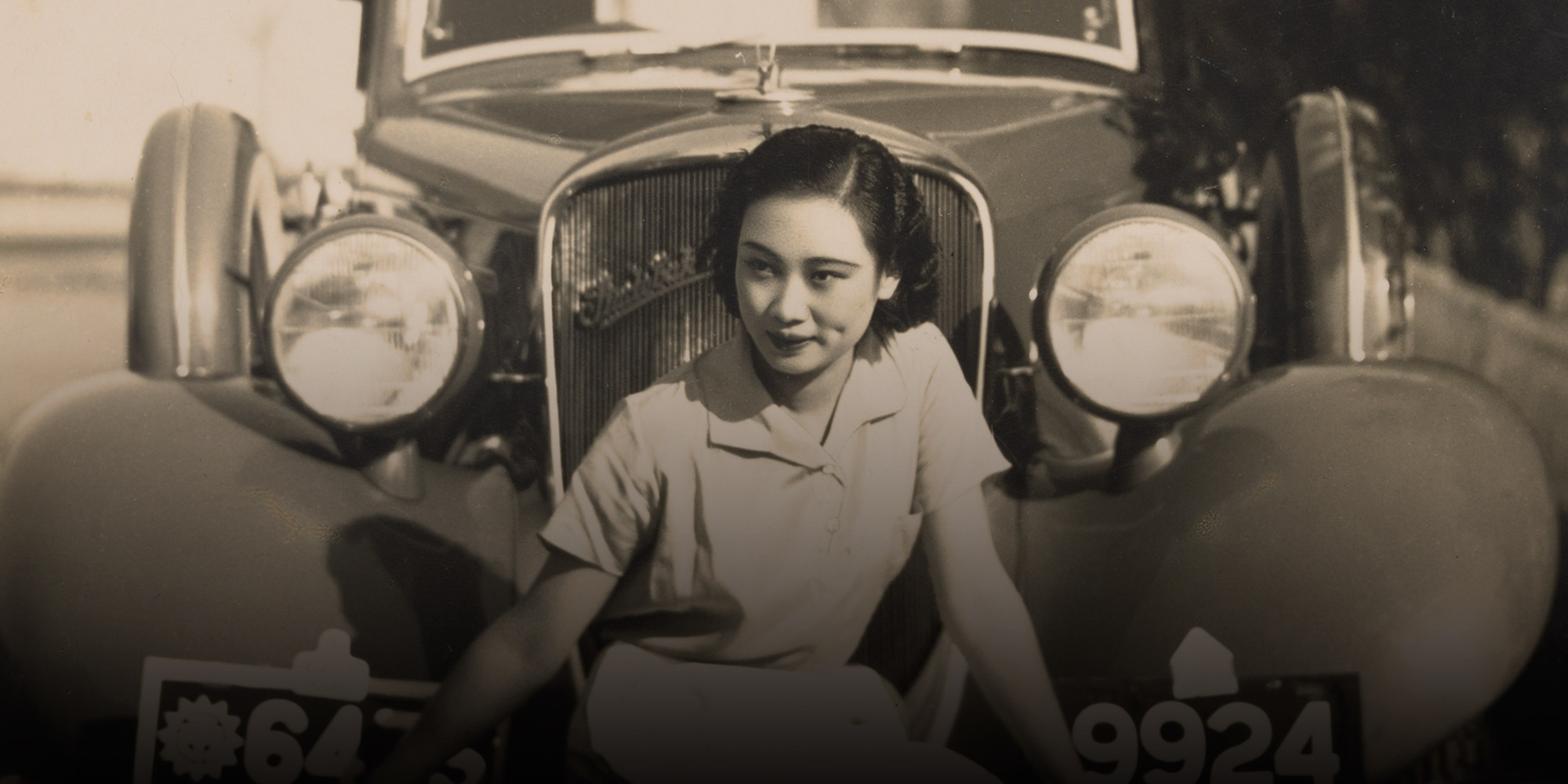

With the euphonious stage name “Butterfly Wu,” or “Hu Die” in Mandarin, the actress born Hu Ruihua starred in numerous films during the golden age of the film industry in Shanghai, once touted as the “Hollywood of the East.”

Born in 1908, Hu traveled and lived in different cities all over China with her family while growing up, allowing her to learn Mandarin, Cantonese, and Shanghainese. When the country’s first film actor training school opened, she was among the first students to enroll. After graduation, Hu debuted in the film “Amid the Battle of Musketry” at the age of 17 as a supporting actress. Three years later, she signed with the Mingxing Film Company, then one of the country’s most influential studios, and was offered a salary a hundred times greater than the average monthly wage in Shanghai, and she soon became one of the most sought-after actresses of the 1930s.

Hu showed off her talent playing a variety of characters, including teachers, prostitutes, servants, celebrities, and laborers. Her role as Red Maiden in the 1928 film “The Burning of the Red Lotus Temple,” as well as its sequels, propelled her to stardom but also stirred up controversy, with critics calling her a bad influence on children for distracting them from their schoolwork. According to Zhang Zhen, a professor of film studies at New York University, to improve her performance, “Hu learned swordplay and embraced the risky practice of flying through the air, suspended by a wire, with dexterity and grace.” Her portrayals of strong female characters like the Red Maiden attracted a huge fan following and were an inspiration to many working-class women.

In addition to her innate acting skills, Hu was always willing to experiment with new filming techniques. In 1931, she starred in the first Chinese film with spoken dialogue, “Sing-Song Girl Red Peony.” Compared with her fellow silent film stars — most of whom were from southern China and had trouble speaking Mandarin — Hu made the transition with ease.

Two years later, Hu played a pair of twins with contrasting personalities with the help of special effects in “Twin Sisters,” which earned her critical acclaim and is to this day considered her best film. Mei Lanfang, one of the brightest stars of Peking opera, expressed his appreciation after watching Hu’s 1940 movie “Chen Yuanyuan, the Beauty.” “Hu Die has her own style of expression,” he said. “Her strength is in her natural composure, and from this we can see the depth and refinement of her character.”

Hu was well-known for her positive attitude and professionalism, and became an icon for modern Chinese femininity. Zhou Jianyun, head of the Mingxing Film Company, sung her praises, too: “That Butterfly Wu enjoys unrivaled admiration is because she possesses the rarest virtue: reliability,” Zhao said. “She is always punctual, and never acts like a celebrity.”

Hu’s influence was not limited to China. She acted as a cultural ambassador and promoted Chinese culture and films abroad. In 1935, as a member of the Chinese delegation, Hu attended the Moscow International Film Festival and toured Europe. Her travelogue was published in China, where it received overwhelmingly positive feedback from readers.

At the time, Chinese actors were pigeonholed as conservative and moderate compared with their Hollywood counterparts. Celebrities often wore long qipao, a type of traditional dress that covers most of the body, showing only parts of the arms and legs. However, through photos of Hu, people could see a modern, stylish woman.

“I think my favorite photo is the one of Hu in her tennis outfit, relaxing after a game,” Karen Smith, curator of the SCoP, told Sixth Tone. “It seems so natural: It could have been taken yesterday.” Smith thinks Hu’s real claim to fame is how she was seen as a professional at a time when acting was not considered a good career for women. “She helped change attitudes toward women in film,” Smith said.

Trained actresses like Hu projected the image of a modern professional woman, and Hu’s career lasted much longer than most actresses of her generation. Following her marriage in 1935, Hu didn’t give up her career and become a housewife, but rather continued making films until the 1960s. In 1975, she immigrated with her family to Canada, where she spent the rest of her life and finally passed away in 1989.

From the 1920s to the ’40s, Chinese media would describe actresses using various metaphors. According to Li Zhen, a film history scholar and the exhibition’s co-curator, when female celebrities were compared with flowers, Hu was always described as “the peony” — the most regal bloom, in traditional Chinese culture — for her elegance and grace. Hu maintained her sense of style and eloquence throughout her career, even in her later years, as she faced the inevitability of aging. “This is what real life is,” she said, “and so it is on stage: No one can play the lead forever.”

Editor: Doris Wang.

(Header image: A portrait of Butterfly Wu taken by Chen Jiazhen. Courtesy of her husband’s family)