Why Chinese Filmgoers Don’t Buy Hollywood’s Values Anymore

Back in February, China’s film industry set a world record for monthly sales in a single market, chalking up 10.1 billion yuan ($1.6 billion). Later, the country posted sales of 20.2 billion yuan ($3.2 billion), a figure approaching the single-market record of around $3.6 billion reported by North America in the final quarter of last year. But while China threatens to become the world’s biggest box office, the commercial model that it once sought to emulate — Hollywood — is losing its dominance in the Chinese market.

When China set the new monthly record, its cinemas were full of homemade movies. In March, major Hollywood titles like “Black Panther,” “The Shape of Water,” “Tomb Raider,” “Pacific Rim: Uprising,” and “Ready Player One” all premiered in the country. In the absence of any major domestic releases, the monthly sales of 51.6 billion yuan were only about half of February’s figure.

As early as 2015, moviemakers noticed that Chinese filmgoers preferred domestic films to Hollywood ones. That year, only three Hollywood blockbusters — “Furious 7,” “Avengers: Age of Ultron,” and “Jurassic World” — made it into the top 10 most-watched movies in China. Since then, audiences’ predilections for homegrown movies have only become more obvious.

Some commentators attribute the country’s preference for domestic films to industry manipulation by the Chinese government, which protects the domestic movie business through a variety of novel policies, including recurring blackouts of imported movies during a “domestic film protection month,” strict quotas on imported films, premieres that coincide with those of hyped-up homegrown blockbusters, and restrictions on the marketing campaigns of major Hollywood titles.

But these claims are overblown. In fact, formal quotas on foreign films have been loosened from 20 per year to 34 since 2012, a policy change from which Hollywood films have benefitted most. Hollywood blockbusters also enjoy more screenings and stronger marketing campaigns than other imports. When “Black Panther” premiered last month, it was screened in more than 30 percent of the country’s cinemas in its first week; however, each screening was, on average, only 10 percent full, according to Taopiaopiao, e-commerce giant Alibaba’s movie ticket app.

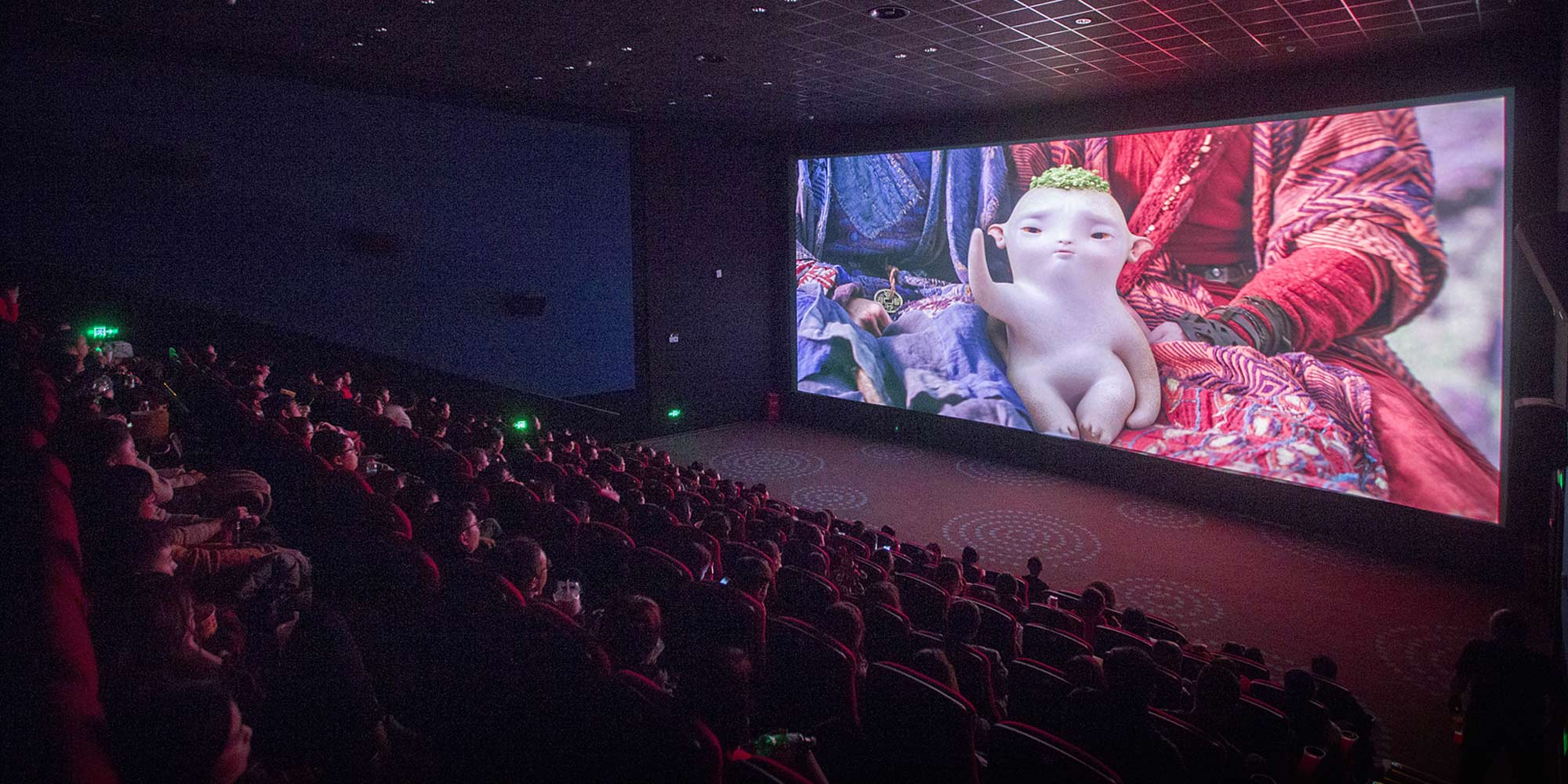

Chinese audiences, not the Chinese government, are turning their noses up at Hollywood. So why is this happening? First, Chinese film production is catching up with Hollywood. The production of the popular war movie “Operation Red Sea,” with its sophisticated editing, choreography, and visual effects, recently drew comparisons to 2001’s “Black Hawk Down,” a high watermark of the genre. Similarly, fantasy movies like the “Monster Hunt” series bear relation to the Marvel and DC superhero franchises.

Of course, Hollywood is still the top dog in terms of its industry capacity and talent base: Chinese filmmakers cannot rival the technical wizardry seen in Steven Spielberg’s “Ready Player One,” for example. But neither is the Chinese movie industry particularly far away from this level, as studios possess huge amounts of funding and ambition to get there.

Admittedly, Hollywood is not just about spectacle; it also produces truly excellent feature films. Yet Chinese audiences seem to care even less about them than they do about the abovementioned blockbusters. “Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri,” “Manchester by the Sea,” “La La Land,” “Darkest Hour” — all have screened at Chinese cinemas, yet none has grossed more than 200 million yuan. “The Shape of Water” premiered in Chinese cinemas only 10 days after it won the Oscar for Best Picture, yet it only brought in a comparatively disappointing 100 million yuan.

All this shows that Chinese audiences aren’t buying the narratives that underpin even the most acclaimed Hollywood productions. Take a few of the films above: “Three Billboards” revolves around the triumph of the individual over the state; “La La Land” is essentially a romance between a couple pursuing personal fame and fortune; and “Darkest Hour” is a reworked version of the triumphant liberal West prevailing over the evil force of fascism.

The well-worn trope of the “American Dream” — an ideology built on an expression of Western individualism and liberalism — is simply not seductive to Chinese audiences, who are increasingly embracing a markedly different form of national pride.

In China, the ideals of the American Dream are paling into significance as the country’s self-styled Chinese Dream produces the growing wealth and status of large numbers of people while promulgating different values: collective effort, patriotism, and self-sacrifice for the cause of national rejuvenation.

Critically acclaimed Hollywood movies — “The Shape of Water” and “Moonlight” are two recent examples — often focus on broader social conflicts in today’s America, such as racial tension, feminism, and LGBT rights. But the reality is that none of these carry comparable resonance in contemporary Chinese society. Tropes like the pursuit of individual rights do not speak to a majority of Chinese filmgoers. The national anxieties of the Chinese tend to be focused around the country’s capacity for continued development and modernization, the sustained enrichment of the majority, and the protection and revitalization of tradition in the face of development. As China flexes its muscles on the world stage, its filmmakers are increasingly exploring forces that conflict with these goals beyond the country’s national borders, such as in the wildly popular “Wolf Warrior 2,” which takes place in an unnamed African nation ravaged by war.

Until about 10 years ago, in the absence of a well-articulated set of national and cultural values, Hollywood stories and the ethics they promoted were aspirational to many Chinese. But now, we’re tired of them. They strike us as conventional at best, irrelevant at worst.

This is not to say that we can’t appreciate a good foreign import. The Indian film “Dangal,” which was released in China last year and told the story of a father training his two daughters in wrestling despite staunch social opposition, was a runaway success here because the central conflicts of the piece — the rejection of socially sanctioned gender roles, the tension between a domineering parent and their children, the hope of escaping poverty and preserving a family’s dignity — are so familiar and relatable.

As a result of the success of “Dangal,” more and more Chinese movie fans are gravitating toward Bollywood fare. The highest-grossing foreign film in the first three months of 2018 was not a major Hollywood title, but a low-budget Indian piece called “Secret Superstar,” whose Chinese box office earnings of 760 million yuan are 10 times larger than what it made back home. Indeed, far from rejecting foreign imports, Chinese filmgoers are calling for quotas to be expanded or for Hollywood’s share of them to be reduced, having realized that many good alternatives lie in the Indian, Japanese, or Middle Eastern markets, among others. Until then, though, most of us are happy to stick to our own domestic productions.

Editor: Matthew Walsh.

Correction: The current box office record for a single market is held by North America, not China.

(Header image: Moviegoers watch the film ‘Monster Hunt 2’ at a cinema in Taiyuan, Shanxi province, Feb. 16, 2018. Zhang Yun/CNS/VCG)