How China Became One American Photographer’s Muse

SHANGHAI — For the past 30 years, American photographer Lois Conner has lugged her vintage-style camera around China, capturing evocative landscapes wherever she goes.

“China is my muse,” a jet-lagged Conner tells Sixth Tone in Shanghai, where an exhibition of her photos is currently on display at the Shanghai Center of Photography.

Conner, now 67, first came to China in 1984 on a Guggenheim Fellowship, a grant for exceptional talents in the arts. Since then, she’s returned every year to record the country’s fast-paced change — and the things that have stayed the same.

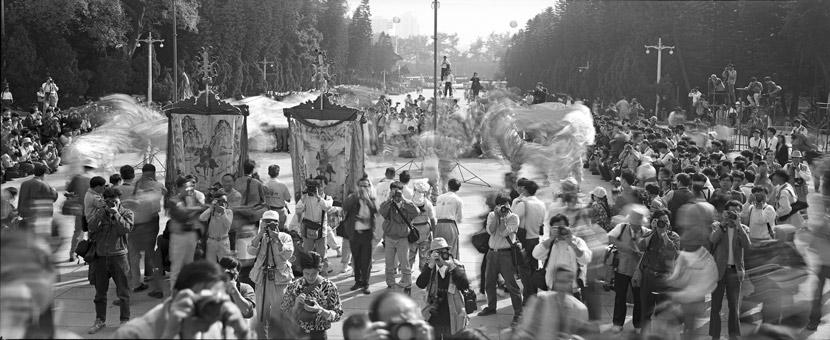

Her Shanghai exhibition is titled “A Long View” — referring to the amount of time she’s spent in China, the format of her photos, and her plodding pace of work with a banquet camera. Popular for formal group photos at the start of last century, banquet cameras tend to be more time-consuming to use than modern models. Conner chose the old-style large-format camera to capture Chinese landscapes — she felt the slow exposure gave her work an exotic beauty, similar to delicate Ming Dynasty landscape paintings.

One of Conner’s most well-known projects features lotuses, a fixture of traditional Chinese paintings and literature. But instead of focusing on the flowers, she hones in on the plants’ drooping seed pods, the patterns created by the leaves, and the reflections the stems cast on still water. The shapes created by the lotuses’ dead leaves and stalks also form miniature landscapes.

Conner makes an effort to familiarize herself with each new place she visits so she can offer a unique perspective on it. “My studio is the world,” she says. “Some people have a studio and make their work there, from their imagination and things they know about. I make it outside in the world.”

Despite her on-the-ground approach, Conner’s process has often been quite lonesome. While creating past works, Conner hid behind the curtain of her camera; that way, no one could tell whether she was Chinese or not. She would be surrounded by tourists and noise, but inside, she felt calm and peaceful.

Speaking with Sixth Tone, Conner shared her source of creative inspiration, her experience of shooting in China, and how she selected her photography subjects. The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Sixth Tone: What brought you to China?

Lois Conner: When I was a graduate student, I was studying photography, but we had to take courses outside of our major. I took this one course that was in Chinese landscape painting from the Ming Dynasty. I was kind of intimidated. We would go to the MET [Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York] and look at paintings. I got to unroll Tang Dynasty scrolls and Ming scrolls and be this close to them — it was just breathtaking. In the beginning, I just said, “I don’t think I’m qualified to take this class because I don’t speak Chinese; I don’t know anything about Chinese art history.” This was pre-Google and pre-everything. When I was looking at the paintings one day, I remarked that I thought that the mountain seemed to be so much from an imaginary world. [My professor] said, “No, they’re a real place in the world, and that’s the Guilin landscape [in southern China’s Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region].” Right at that point, it was like, “OK, I’m going to go see it.” It was very wonderfully strange. I needed to go to the place where, for 2,000 years, painters and poets have gone to write and contemplate the landscape. So that’s originally why I came to China — to go to Yangshuo [near Guilin], to see the mountains on the Li River.

Sixth Tone: What are your influences, and why did you choose landscapes?

Lois Conner: I’m a student of art history across generations and across continents, so my influences are vast. All of my photographs have some kind of relationship to history.

My subject, I always tell everybody, is landscape as culture. None of my photographs are just about nature. I feel like you have to step back and include more for me, to make myself interested. I don’t think my lotuses look like anything that would be Chinese, and that’s good because I’m not Chinese and I’m not trying to make them look Chinese — there’s nothing wrong with that, but that’s not my intention. One picture is about the history of my life; it’s not just about China.

Sixth Tone: How do you choose which landscapes to capture?

Lois Conner: I might go to a place and do absolutely no work, because I don’t really know where to begin. But then I keep going back until I become familiar enough to have something to say that’s my own. I have traveled pretty much around China, but I feel like I haven’t traveled anywhere, because there are so many places. I want to see as much as I can because the more you see, the more knowledge you have to speak from.

Sixth Tone: Could you talk about the photographs you’ve taken in Shanghai?

Lois Conner: I have pictures of Pudong with nothing on it. And later, they took all the boatyards away, and then I have the beginnings of the construction. Two of the biggest buildings in the world are in Pudong. In my lifetime, in a generation, it made that kind of a transformation. I don’t think it’s happened anywhere else. I didn’t start off photographing it, but I’m here and I come [back] every year, so it [Pudong] became my subject. It became my muse.

With the construction here, it’s very different from in the West. When they were building the Bank of China [Building] in Shanghai, it was all done with bamboo scaffolding and people in their bare feet. There’s something just so beautiful and poetic about it, and I’m really interested in this scale of a man to the landscape — so that’s why the people mostly appear small [in my works].

Sixth Tone: Why do you prefer to use a large-format camera and work in black and white?

Lois Conner: I started using a small camera. When I was a young student, I had to take a class and use a big camera on a tripod, and the day I did that, I felt like my life changed. I no longer had to quickly move around with the small camera — it’s on the tripod, I can set it up, I can walk around, I can carry it over my shoulder, but I can pause and look at the landscape. [When I was starting out] you could use color film, but there is something about black and white and fiction that are really close together. There are many color photographers whose work I like, and I am doing bodies of work in color now. But, in the end, I find the power of black and white better for my eye and what I am trying to describe.

I like looking at [photographs] at that [large] size because when you go close, you can read a world, and when you step back, you can still read them from a distance. They change in their meaning when you go closer, and they don’t disappoint because the detail’s there.

There’s a reason I use a banquet camera, there’s a reason I use black-and-white film, and there’s a reason I’m out there by myself. Right now, it’s still working for me.

Editor: Julia Hollingsworth.

(Vertical image: ‘Colossal Buddha,’ taken in Leshan, Sichuan province, 1986. Courtesy of Lois Conner)

(Header image: ‘Triangle Lotus,’ taken in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, 1998. Courtesy of Lois Conner)