How Long-Unpublished Press Photos Bring Life to Chinese History

This is the fourth article in a series on “Old Photos,” a Chinese-language publication that collects images of the country’s modern history. Parts one, two, and three can be found here.

In the 1990s, the Xinhua News Agency — China’s state newswire — began opening its photographic archives to the public. It was a paid service: In 1996, for example, a 5-inch black-and-white photograph cost 55 yuan (then around $6.60) to reprint and use. Back then, it was fairly easy to access the archives, as long as you had a letter of introduction from your employer. I visited the Xinhua archives in Beijing several times, sending staff scurrying off to the storeroom to retrieve albums for me to peruse. Sometimes, they came back pushing small carts piled high with thick binders of photos they would stack on my desk.

I vividly remember the faint musty smell that came off the yellowed pages of those albums as I flicked through them, glancing back and forth between the photos and the typewritten captions beneath them. Some captions were accompanied by decades-old editorial remarks, such as “unfit for publication,” “underexposed,” or “crop out the person on the left.” Such comments are themselves food for thought: They reveal the standards of the period by which press photographs were taken and selected.

I used the archives a lot during the first few years after my team and I started printing a series of photography books, “Old Photos,” in 1996. I dredged up many images deemed unfit for publication, acquired the right to use them, and included them in the book, which was issued through a state-owned publisher in eastern China’s Shandong province. Certain shots left a profound impression upon me.

One such image was a photograph of Mao Zedong and Pan Guangdan, a famed educator and one of the founding fathers of modern Chinese sociology. Pan earned his bachelor’s degree in 1924 from Dartmouth College in the United States and his master’s from Columbia University in 1926. After returning to China, he taught at some of the country’s leading institutions, including the renowned Tsinghua University in Beijing.

The photograph is dated to Oct. 23, 1951, and was taken in Beijing. Pan is attending a meeting of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, the country’s political advisory body. During a break in proceedings, Mao seems to have stepped down from his chairman’s podium and struck up a conversation with Pan, who at the time was a member of the Government Administration Council’s committee on culture and education. Pan lost a leg due to a sports injury at university and found it difficult to walk. Mao might have seen Pan remain seated while those around him left, and so have gone down to say hello.

Pan is leaning with his right hand on his walking stick so as to stand up straighter in Mao’s presence. In his left hand, he clutches a pipe. The two of them might be sharing a joke, or Pan may simply be happy to be the subject of Mao’s attentions. To me, the photographer has captured something of the delicate relationship that existed between the Communist Party’s leaders and well-known public intellectuals during the nascent years of the People’s Republic of China.

Photographs of Mao and other Chinese leaders usually place them in the center of the shot with their faces visible. But this image shows Mao from behind and off to one side. Mao’s posture — he is standing very straight, his head bent forward slightly — seems to convey a certain modesty and respect toward a highly educated individual. In the 1950s, as China emerged from a century of conflict, people like Pan were considered crucial for national rejuvenation.

But in a matter of years, the political winds turned on intellectuals like Pan. In 1967, one year into the Cultural Revolution, Pan went from being courteously received by the highest office in the land to being persecuted for perceived rightist sympathies. His health deteriorated rapidly, and he died from severe illness at the age of 69. When the Cultural Revolution ended 10 years later, Pan’s name was rehabilitated.

The next photograph comes not from the Xinhua archives, but from the famed Taiwanese collector Qin Feng. It shows Chiang Kai-shek, who chaired the Kuomintang (KMT) government for most of the period between 1928 to 1948 at a time when the Nationalist Party ruled over much of China. The photograph is beautifully framed, but was classified as “unfit for publication” by the KMT because Chiang has his back to the lens. I don’t think anyone on the Chinese mainland saw the image before I published it in “Old Photos.”

Chiang seems to be paying homage to his ancestors in his hometown of Fenghua, in eastern China’s Zhejiang province. Taken not long after he announced his decision to relinquish power in January 1949, the shot depicts Chiang gazing down at the town from a nearby mountain. His son Chiang Ching-kuo stands by his side.

This was Chiang’s last visit home before he and his Nationalist armies fled to Taiwan. According to the famed Taiwanese photograph collector Qin Feng, who provided me with the image, this photo was only deemed fit for publication after both Chiang and his son had died.

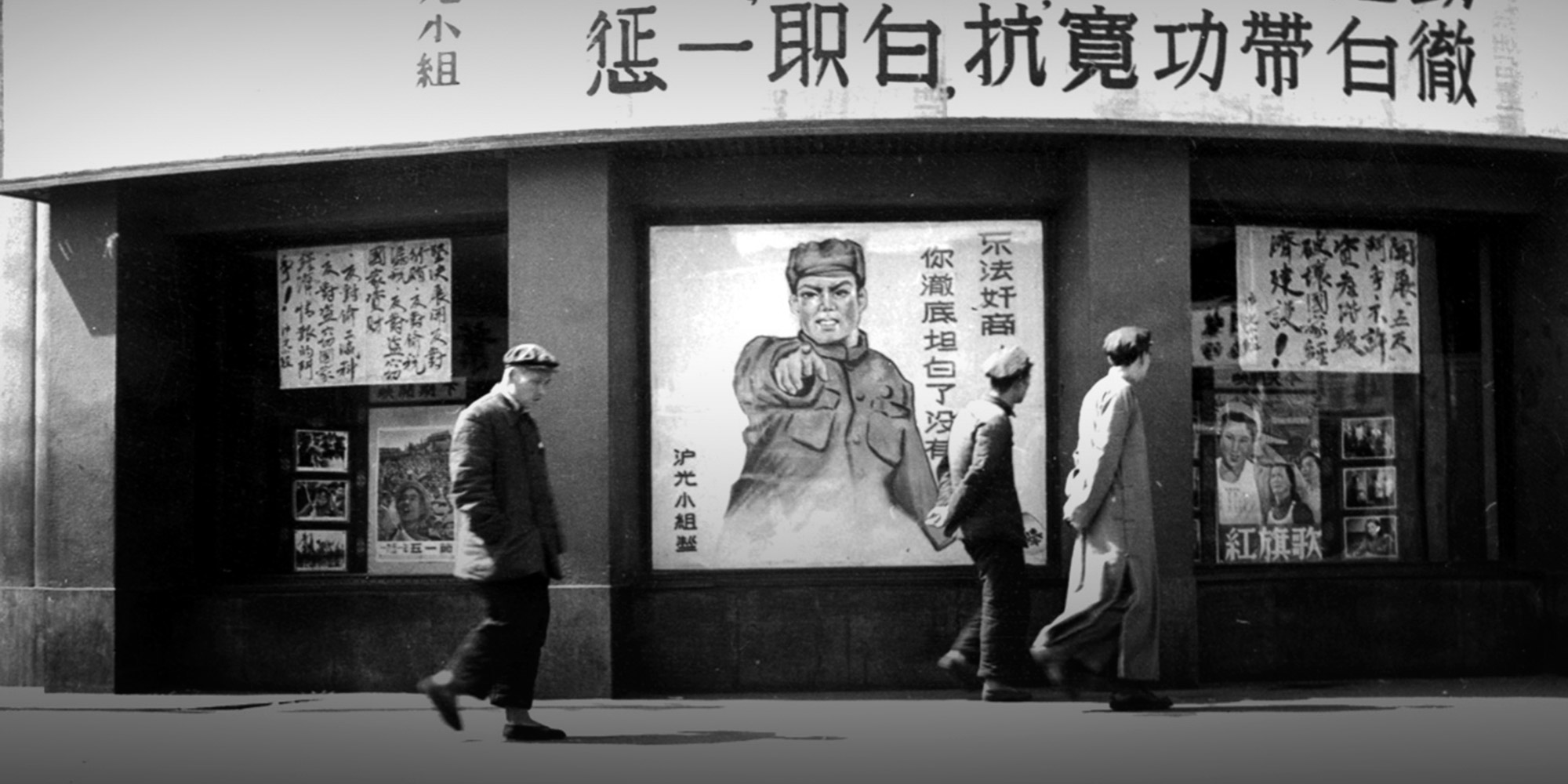

Two other images marked as “unfit for publication” also made the pages of “Old Photos.” They were taken during the Three-Anti and Five-Anti campaigns of 1951 to 1952, two Party-led political movements that first aimed to rid the country of corruption, waste, and excess bureaucracy, and later targeted private business owners, landlords, and perceived capitalist sympathizers.

One shot, visible at the head of this article, depicts a street scene outside Shanghai’s Huguang Movie Theater, while the above image portrays members of a Party propaganda brigade leading a choral song in one of the city’s residential lane communities known as longtang.

Both photographs aim to capture the strength and ubiquity of the campaigns. There is no space for the movie posters that once adorned the cinema’s entrance; instead, the building is dominated by a huge slogan commanding people to stringently punish those who refuse to confess to their crimes and treat those who voluntarily confess with leniency. In addition, the once-serene longtang is transformed into a crowded sea of heads as people of all walks of life are taught the songs of the campaign.

It’s difficult to know for certain why these pictures couldn’t be published. Perhaps they were out of keeping with the meticulously orchestrated news photographs that were already becoming the norm at this time. In comparison, the composition of these photos is loose, their subjects ill-defined. The movie theater gives the impression of an ambiguous relationship between the stooped, somewhat listless-looking middle-aged men and the arresting slogans and images behind them. The mood of the image sits uncomfortably with the political messages that seem to emphasize clarity, self-belief, and righteous action.

I always felt that Susan Sontag put it best in “On Photography,” when she discusses how the Italian film director Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1972 documentary “China” — which he filmed at the invitation of the Chinese government — was perceived as anti-Chinese by many in the country at that time. In China, she wrote, “no space is left over from politics and moralism for expressions of aesthetic sensibility, only some things are to be photographed and only in certain ways.” The very lifeblood of journalism is objectivity and freedom, but Chinese photojournalism of the 1950s and ’60s was largely dictated by a “message-first” approach, and the myriad effects of politics on daily life were rarely publicized.

The passing of time enables us to see with more clarity which photographs hold value. Sometimes, the way we felt about a photo in the past can be worlds apart from the way we feel about it today. The fact that the public can finally view the above photos shows that today we are no longer where we were yesterday.

Translator: Owen Churchill; editors: Zhang Bo and Matthew Walsh.