Testing Times: The Lifelong Cost of Top Marks

JIANGSU, East China — In late June every year, thousands of high school students in Nantong receive their results from the gaokao, China’s notoriously grueling college entrance exam. For the majority of them, it is a time of celebration: The historically underdeveloped coastal city is famous throughout China for the vast numbers of high schoolers it sends on to the country’s universities.

This year, more than 96 percent of Nantong’s gaokao students achieved the minimum score required to enter university, according to the municipal education authority. That proportion is staggering when China’s fiercely competitive university admissions system is taken into account: Only around 40 percent of the nation’s high school graduates test into college, according to online news portal China Education Online.

In a city that still casts envious glances at its more prosperous neighbors in Shanghai, Suzhou, and Hangzhou, many families in Nantong laud such impressive enrollment figures as proof that their city’s famously rigorous teaching standards enable their children to rub shoulders with the region’s well-heeled social elite.

But there are problems with the Nantong model. Across the city, public schools routinely subject students to 12-hour days, seemingly endless practice exams, and restricted contact with family members. While this method yields results, both teachers and former students claim that the system is stressful, demoralizing, and damaging to their health.

In the suburban county of Rudong, 2018 was a record-breaking year: More than 99 percent of all of its high school graduates achieved the minimum entry requirements for college. At Rudong County High — a renowned local boarding school — five students ranked among the top 100 scorers in the whole province.

However, Jianguo — a physics teacher at the school, who asks that Sixth Tone not reveal his surname in order to protect his identity from his employer — says that the news didn’t exactly fill him with joy. His 16-year-old son will start his second year at Rudong County High in September, and Jianguo knows that the intensive study over the next two years will profoundly shape the boy’s life and future prospects. “I can already see he’s nervous ahead of every exam; he’s constantly running off to the toilet and struggles to fall asleep at night,” Jianguo says. “But there’s no way around it: He has to pull himself through the next two years.”

For the entire three years they spend at Rudong County High, students take compulsory, subject-specific practice exams every week and more comprehensive tests once a month. The latter exams simulate the gaokao, and the results tell students which universities — if any — they would get into if it had been the real thing.

To prepare for the gauntlet of test-taking, the school strictly manages students’ daily lives. Classes start at 6:30 a.m. and end around 6 p.m. After dinner, evening self-study sessions run until around 9:40 p.m., when students retire to their dormitories or — more commonly — stay up even later to complete assignments. Parents are only allowed to visit their children for around half an hour a week, every Sunday afternoon.

Rudong County High’s teaching methods are largely representative of the Nantong model as a whole. Although several of the city’s current high schoolers privately confide that they feel overwhelmed by the amount of study hours, none are willing to offer their names out of concern that their schools will find out.

Former students, however, are more forthcoming. Yuan Linna sat the gaokao in a rural district of Nantong in 2001. She got the second-highest score in her school, tested into law school at the prestigious Fudan University in Shanghai, and now works for a foreign-owned bank in the same city. “Throughout high school, my sole motivation for learning was that I had to get out of Jiangsu,” she says, referring to the province in which Nantong is located. Although the city’s economy has grown since China launched its wide-ranging reforms in the late 1970s, locals still tend to view it as less cosmopolitan than nearby megacities. “All the hard work of the previous 12 years [of compulsory education] was for a better life in a big city like Shanghai or Beijing,” Yuan adds. “Seventeen years on, it hasn’t changed at all.”

She claims that Nantong’s intensive study model had an irreversible impact on her health. “My former female classmates are all around my height — few of us are taller than 160 cm tall,” says Yuan, who at 157 cm is around 4 cm shorter than the average Chinese woman of her generation. “Lack of sleep became an issue as early as primary school — even then, homework assignments kept us up until 11 p.m.” The U.S.-based organization National Sleep Foundation recommends that 6- to 13-year-old children get nine to 11 hours of sleep a day in order to develop properly.

When asked which part of Nantong’s educational culture she found most beneficial, Yuan is unequivocal. “It made me good at exams,” she says. But she stops short of praising the Nantong model. “I’ve basically forgotten what I learned in high school. I could remember things well by repeatedly reinforcing them over a certain period of time. But that didn’t help me later on in life. I didn’t even know how to plan my future and what I really wanted out of life, which was very depressing.”

Jianguo says that students at Rudong County High are treated more leniently than their peers at a school in the neighboring county of Hai’an, where classes commence at 6 a.m. and evening study time doesn’t finish until 11 p.m. “Our principal keeps reminding us of how [the Hai’an school] is preparing for the gaokao, cranking up the pressure on teachers as well as students,” he says.

Nantong’s top schools are more or less evenly spread across the city’s various districts and counties. High local demand for limited spots means that some parents use personal connections to illicitly enroll their children in schools outside of their districts of residence, Jianguo says. He adds that many parents see the extracurricular self-study sessions offered by high-ranking boarding schools as a way to avoid costly private revision classes for their children.

Although teachers are not contractually obliged to teach extracurricular classes, Jianguo says that salary packages at his school are tightly linked to after-school availability. Like many public servants, Chinese teachers receive part of their pay in subsidies — discretionary payments made by schools in addition to the teachers’ basic salaries. At Rudong County High, Jianguo says, “we’re mobilized to give extra classes to students … Those who decline to teach after-hours get 30 percent of their subsidies deducted. This money is then used to reward those who do work overtime.”

Jianguo believes that Nantong’s educational model — based on compulsive, round-the-clock study and testing — leaves all parties at a disadvantage. “Who wants to have extra classes? Nobody! Students don’t, and neither do teachers. And parents actually don’t want it either — they don’t want to watch their children suffer that much!” Jianguo says.

Similarly intensive teaching styles can also be found in Nantong’s primary and middle school classrooms. The city’s gaokao scores are so impressive partly because public high schools strictly limit the number of places available to incoming middle school students. In essence, high schools can skim off the top 50 percent of middle schoolers on the basis of their results on the zhongkao — the high school entrance exam. This tactic forces less able students into vocational schools and technical colleges, where they will not take the gaokao and likely go directly into the job market at the age of 15.

In response to complaints about elitism in high school enrollment, Nantong’s educational bureau plans to increase admission this year to the top 60 percent of zhongkao examinees — equivalent to the levels in major cities like Shanghai and Beijing. But educators claim that a corresponding increase in the number of teaching staff is also needed to prevent overcrowding and guarantee teaching quality. These issues not only blight high schools, but also good middle schools, which are increasing their own intake quotas to satisfy parents who are hopeful that their children may later get a chance to study for the gaokao.

Gu Ronghua has taught Chinese at the city’s leading middle school for more than 20 years. Her school, too, frequently demands that both students and teachers work 12-hour days. This summer, more than 900 students will graduate from Gu’s school, and that number is slated to rise to 1,200 and 1,400 in the next two years, respectively. “But the number of teachers always stays the same,” she says with a sigh. “That means that class sizes keep expanding, from around 50 [students] to nearly 70. I think that’s unfair, because kids definitely won’t be able to receive as much individual attention from their teachers [as they could have otherwise].”

In order to accommodate the projected increase in student numbers, Gu’s school plans to convert part of its playground into new classrooms. “The authorities have not demonstrated any willingness to address the difficulties,” she says.

Cao Bingsheng, a veteran teacher at Nantong Normal College — a junior vocational school whose students do not take the gaokao — welcomes plans to open up Nantong’s high schools to more students, but believes that officials must swiftly deal with growing numbers of want-away teachers who cite high stress and low pay as reasons to leave the city. He adds that while cities like Shanghai and Suzhou have always poached teachers from Nantong, these days even less-developed cities like nearby Yancheng are getting in on the act. “They offer competitive salary packages,” Cao says. “Yancheng offers teachers an annual salary package of 300,000 yuan [$45,000], even though the city is poorer than Nantong,” where the equivalent package is less than 100,000 yuan, he says. “So nobody is attracted to schools in Nantong!”

Cao has taught in Nantong for 35 years, but now says that the city is failing to help its teachers lead decent lives. “With all of the stress of improving their students’ academic performances, most teachers here don’t have it easy.”

In September, Jianguo — the physics teacher — will watch his son move into the final, exhausting two years of Nantong’s public education system. But with so much time taken up by studying, Jianguo still doesn’t know what his boy is truly passionate about. “His emotions are basically controlled by his exam results,” Jianguo says. “All of his happiness in life now comes from good test scores, and we can do nothing to change that.”

Editor: Matthew Walsh.

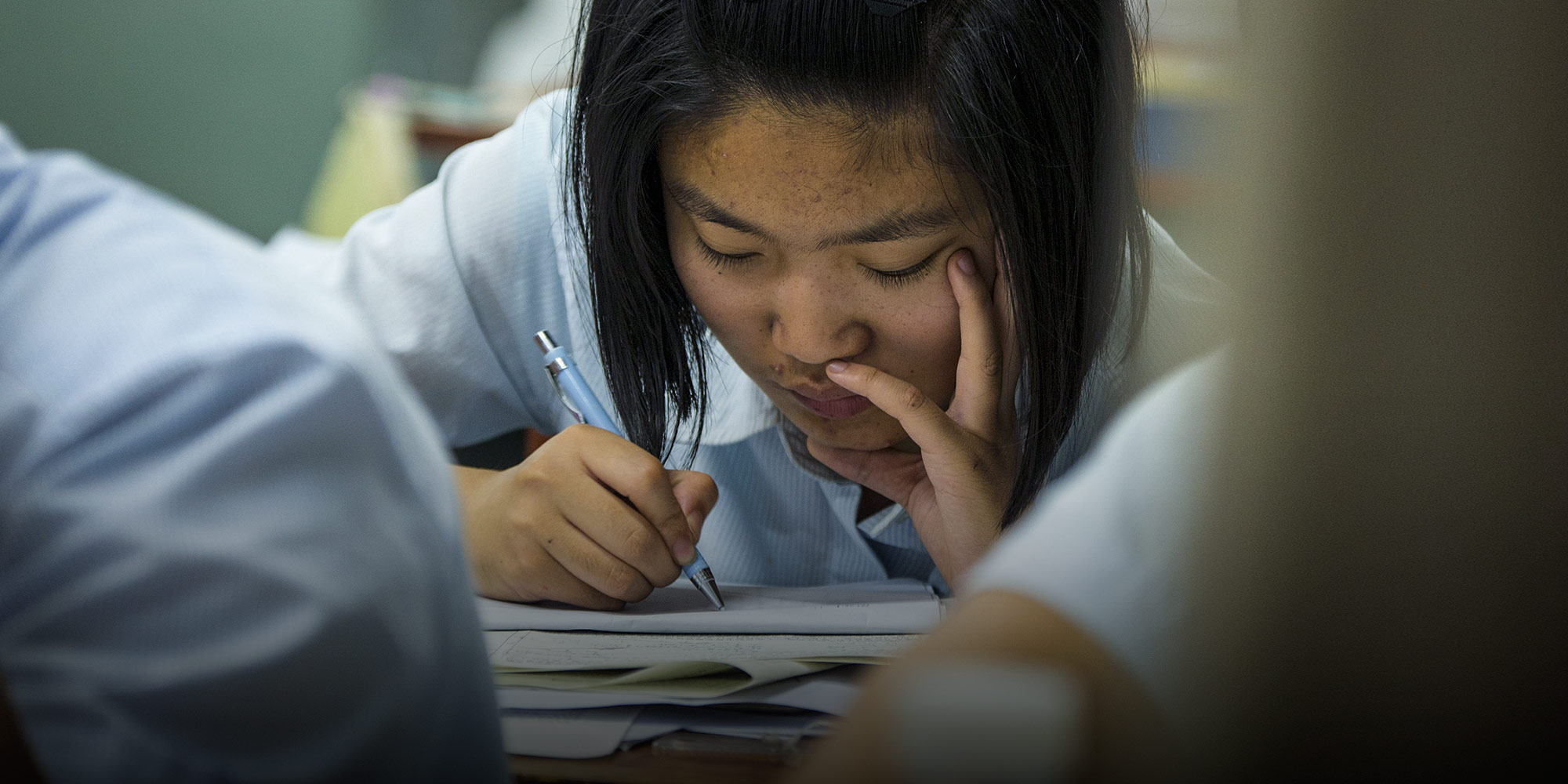

(Header image: A high school senior studies in a classroom in Nantong, Jiangsu province, May 25, 2016. Xu Jingbai/VCG)